Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Leave it to a former professional wrestler to utter one of the few insightful televised comments made regarding the blitzkrieg of coverage that has accompanied the invasion of Iraq.

“This war is being covered much the same way you would cover the Super Bowl,” said Jesse Ventura, who in various incarnations has also been a Navy SEAL and governor of Minnesota. Now, as one anchor noted, Ventura is “part of the family” at MSNBC, the 24-hour cable news channel where he made this observation last week.

Ventura got it just about right. Superficially, the aptness of his analogy can’t be denied. The “embedded” reporters in the field with the troops are like the play-by-play sportscasters calling the action. And the retired generals on the payroll of all the networks are the equivalent of ex-jock color commentators offering insights about how well the game plan is going, using the knowledge gained from when they used to play.

But there’s a deeper analogy that Ventura missed. In the business of covering sports, there is a breed of reporter derisively referred to as “homers.” They are writers and broadcasters who attempt to curry favor with fans by relinquishing the role of neutral observer, becoming instead boosters of the hometown team. What we’re seeing in much of the TV coverage of the war so far is unabashed homerism. It is manifest in ways both subtle and blatant, from the small American flag constantly waving in the corner of the Fox News Network’s war coverage to the pronouncement of CNN analyst David Hackworth, a retired colonel who confidently predicted last week that once the fierce sandstorms that forced troops to hunker down subsided, “it’s going to be slam, bam, goodbye Republican Guard and on to Baghdad.”

Hoo-yah.

Televised groupthink

For a democracy during a time of war, a media pervaded by homers can have a disastrous effect. The danger is that Americans, exposed to an overload of flag-draped reportage, will be deluded into believing that the rest of the world perceives this war the same way we do.

Some of it is understandable, perhaps even unavoidable. It’s not realistic to expect “embedded” journalists, whose very survival is in the hands of the soldiers they are covering, to retain a healthy skepticism.

Take, for example, a report in last week’s New York Times that quoted NBC News correspondent David Bloom. The article, while noting that Bloom pledged objective reporting, also quoted him as saying this about the troops with whom he is embedded: “They have done anything and everything that we could ask of them, and we in turn are trying to return the favor by doing anything and everything that they can ask of us.”

More disturbing is what’s happening in studios of television news organizations.

In an opinion piece published last week, Editor & Publisher magazine editor Greg Mitchell noted: “On Monday, I received a call from a producer of a major network’s prime time news program. He said they wanted to interview me for a piece on how the public’s expectation of a quick victory somehow was too high.”

The producer, Mitchell explained, didn’t want to “focus” on the media’s role in shaping those expectations.

“I asked him where he thought the public might have received the information that falsely raised their hopes. … The problem, I suggested, is that most of the TV commentators on the home front appear to be just as ‘embedded’ with the military as the far braver reporters now in the Iraqi desert.”

Given our media culture, it’s not difficult to see why the American public expected that overthrowing a country the size of California would only take slightly longer than a trip to the drive-through window for a Big Mac.

Machiavellian tactics

In the weeks leading up to the war, the coverage was heavily skewed in favor of those beating the war drums, according to the nonprofit group Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting. Looking at network newscasts over a two-week period beginning Jan. 30, the group found airtime was dominated by “current and former U.S. officials,” largely excluding Americans who were “skeptical of or opposed to an invasion of Iraq.”

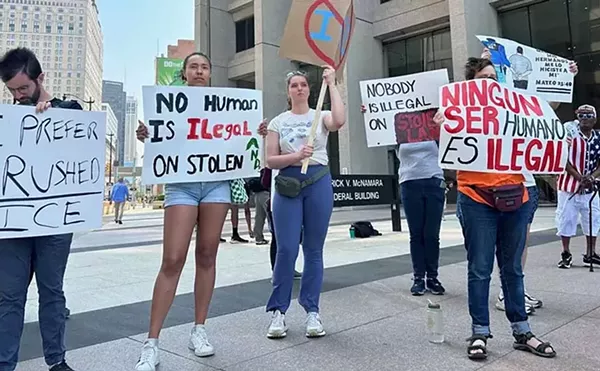

Specifically, the study found that “sources affiliated with anti-war activism were nonexistent. Of the four networks combined [ABC, NBC, CBS and PBS] just three of the 393 sources were identified as being affiliated with anti-war activism — less than 1 percent.”

By way of explanation, CBS anchor Dan Rather, being interviewed by CNN, observed that more voices of dissent aren’t being heard on the airwaves partly because “the White House and the administration power is able to control the images to a very large degree. It has been growing over the years. And that’s the context in which we talk about, well, how much coverage does the anti-war movement merit? And I think it’s a valid criticism that it’s been underreported.”

Responding to Rather’s comments, Katrina vanden Heuvel, editor of The Nation, told CNN, “What Dan Rather said is also interesting, in referring to the control that this White House exerts on the press, again, an untold story because people are fearful of losing access. This White House treats anyone who dissents from them with truly — well, Machiavellian is probably too kind a term. But I think that what’s important is that the cable TV or even broadcast TV, which is where millions of people get their news, has treated the opposition to this war as on another planet, as irrelevant.”

Half-truths and lies

The illusion propagated by round-the-clock coverage of the war is one of expansive reporting that provides full access to all viewpoints. After all, with 24 hours to fill, there’s certainly time to offer up a broad range of information from diverse sources. But that simply isn’t happening, says Christopher Simpson, professor of communications at American University in Washington, D.C.

“The range of opinion in mass media [in America] is extremely narrow compared to the rest of the world, including some very repressive countries,” Simpson says. “An extremely narrow band of ideas is presented.”

Coverage might seem more balanced than it really is because there is so much of it.

“Information is coming at us like water from a fire hose,” explained Simpson. “It is impossible to absorb all this information, much less understand it.”

Simpson described what he called a “cumulative assault on the overall consciousness of the audience,” creating an atmosphere where “people are pressured, often intensely, to resign themselves to accepting half-truths and sometimes intentional lies.”

Money-makers

There’s another reason people aren’t hearing many opposition voices on TV these days. Patriotism, apparently, pays. A recent story in Broadcasting & Cable magazine revealed results of a poll that found viewers had “little interest in anti-war protests.” The article quoted an executive from the Frank N. Magid Associates, the media consulting company that conducted the poll, as saying, “Obviously you have to give both sides of the story. But how much you devote to [protests] and where you place it in your newscast becomes an issue.”

Consequently, what people heard instead were views like those expressed by Vice President Dick Cheney when he appeared on NBC’s “Meet the Press” in mid-March. Asked by host Tim Russert about the possibility of this being a long and bloody battle, Cheney replied: “Well, I don’t think it’s likely to unfold that way, Tim, because I really do believe that we will be greeted as liberators. … The read we get on the people of Iraq is there is no question but what they want to the get rid of Saddam Hussein and they will welcome as liberators the United States.”

Now comes the reality check.

“This is not about liberation. This is about oil. This is about Israel. This is about a lot of things, but it’s not about liberating the Iraqi people. Nobody, nobody in this part of the world believes that it is …” said Newsweek magazine Middle East bureau chief Chris Dickey during an interview on CNN broadcast at 1:30 a.m. on Sunday, March 30. “This is going to be a hostile occupation no matter how we try to put a good face on it and while some people will cooperate with us, many will not, and we are going to alienate and are alienating the entire Muslim and Arab world in the process.”

In a separate interview on National Public Radio, Dickey laid the blame for Americans’ failure to comprehend what’s happening at the feet of American media.

“Unlike the last Gulf War, everybody here [in the Middle East] can have, if they want, access to CNN and to the other Western media, but they can also get access to all the Arab satellite stations, of which there are many and which are presenting a very, very different picture of this war, including a lot more extensive briefings by the Iraqis and infinitely more substantial coverage of the victims of the war. So there is this sense that you get, flipping back and forth between the Arab stations and the British or American stations, of this kind of massive aphasia, where things are just wildly out of sync. And ironically we’re in a position these days — and I never thought this would happen — where the briefings being given by the Iraqis are more credible on many counts than the briefings being given by the British and American briefers in Qatar.”

Compare that to an observation by CNN’s Judy Woodruff, trying to make sense of bombing footage being beamed in from Baghdad: “So, again, just in the last minute or so, a big explosion in Baghdad. We don’t know where it is. But if we are to believe — and there is no reason why we shouldn’t believe coalition military leaders — what they are hitting is very heavily targeted. …”

In other words, not an accident like the one which occurred in a Baghdad marketplace last week, where 15 Iraqi civilians were killed by two explosions for which the American military refused to accept responsibility, even though foreign reporters pointed out how far-fetched it is to believe two errant anti-aircraft rockets fired by Iraqis could land in such close proximity to each other.

Hiding the gore

While the rest of the world is seeing, in Dickey’s words, “dead children, dead soldiers, dead bodies, ravaged cities,” American broadcast journalists are debating just how far they should go in “sanitizing” what they air. In seemingly endless loops, we’re exposed to hour after hour of tanks racing across the desert, whiz-bang graphics and animations of weapons systems and long-distance shots of missiles exploding in the night.

As Washington Post media critic Howard Kurtz told CNN: “I think the war perhaps has been a little too sanitized. But I don’t think that’s because of government-imposed restrictions. I think that is because American media organizations are reluctant to show gruesome pictures of dead bodies and injured civilians. We’ve seen a little bit of that, but not that much.” (It should be noted that Kurtz, never known for substantial criticism, hosts a weekly show on CNN, meaning he gets a paycheck from one of the institutions he is supposed to hold to account.)

And the reason for that, apparently, is that the American public doesn’t have the stomach to look too closely at the consequences of a war their tax dollars are financing. That was made apparent during a roundtable discussion on Fox hosted by Brit Hume, who noted that showing just one still picture depicting the corpses of several American airmen who had apparently been executed, “the reaction from the viewers was outrage at what we had shown. Now, it was nothing compared to what was aired by Iraqi TV and then sent all over the Arab world by Al-Jazeera.”

If depicting war carnage too graphically is off-limits because it offends the sensibilities of the viewers, jokes about the destruction caused by dropping 1,000-pound bombs on a city of 5 million people are apparently just fine. There didn’t appear to be much backlash from viewers when MSNBC analyst Ken Allard, a retired Army colonel, quipped, “We have a 4 a.m. wake-up call in Baghdad. Good morning. Do you know where your dictator is? We do. We just had 10 fairly impressive blasts in this area that you see here behind me on the screen.”

Be your own editor

If jokers like Allard aren’t chuckling in the studio while corpses pile up in Baghdad, then the networks are filling airtime wrapping themselves in the flag. Again, it is an approach that pays.

The Washington Post reported last week reported that Cleveland-based consultant McVay Media had issued a “war manual” that advised clients to “Get the following production pieces into the studio NOW: Patriotic music that makes you cry, salute, get cold chills! Go for emotion.”

The most blatant attempt to tug at heartstrings can be found in MSNBC’s “America’s Bravest” photo wall of pictures submitted by loved ones. Anchor Natalie Morales described this as “an enormous display of love, pride and support to our military men and women.”

In one of the few introspective pieces airing on TV since the war began, ABC News correspondent Robert Krulwich urged viewers to look at the coverage carefully. He talked about the logos used by different networks, and their subtexts. Fox and NBC, he noted, have adopted the administration’s parlance by employing the rubric, “Operation Iraqi Freedom.” His network adopted the title “War With Iraq,” suggesting a more neutral approach. Same with CBS, with its “America At War” and CNN’s “War In Iraq.”

And, he told viewers, “just as the TV networks have their strategies, so do governments. The Iraqis and Americans are very consciously fighting this war on television.”

Asked by Metro Times in a phone interview whether he thought the media served as a propaganda tool for our government, Krulwich pauses a long while before offering an answer.

“That’s a kind of complicated question,” he finally responds. “Sometimes it does, and sometimes it doesn’t.”

He concluded his televised piece this way:

“The bottom line is you are going to see all kinds of images … that have been chosen to attract you, hold your attention, make you wince, make you mad, make you proud, make you cry. And you will not always know who made these images or why. And this time you will have to be your own editor, but with a skeptical eye. You could learn a lot. More, maybe, than ever before.

“The truth is out there. You just have to work at finding it.”

Curt Guyette is the news editor of Metro Times. E-mail cguyette@metrotimes.com