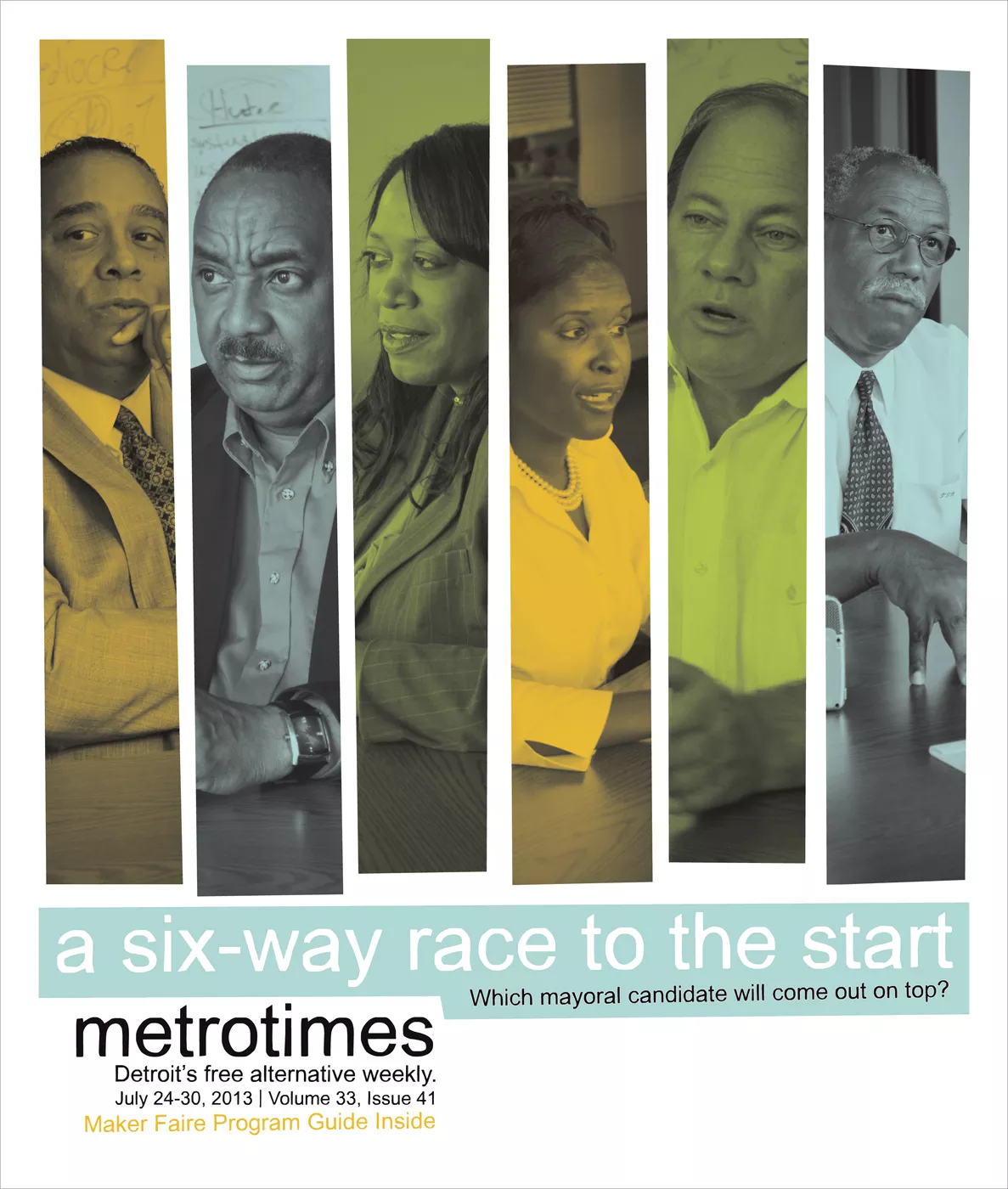

With less than two weeks to go before the Aug. 6 primary, Metro Times invited the six top contenders vying to become the city of Detroit’s next mayor to sit down and participate in one-on-one interviews.

Their responses, unfiltered by copy, are presented in a simple question and answer format. To ensure each candidate had the opportunity to address Metro Times’ readers, and the space considerations necessary for that, we made the decision to truncate their responses so you could read the most salient aspects of their answers. Each interview is available, in its entirety, on our website at metrotimes.com.

We strongly urge you to take the time and read what each candidate had to say, in full. Whether you agree with their positions, these six men and women all share one common thread: Their love for the city of Detroit. If only love could reverse 60-some-odd years of problems in the making.

It’s hard to dismiss the ramifications of this primary, where tectonic shifts in power and circumstance continue to unfold — from gubernatorial appointments and the recent entrance into Chapter 9 bankruptcy. After the ballots are counted, and the election’s top two vote getters begin making their case to the city’s more than half-million registered voters, the eyes of Detroit’s tri-county neighbors, the state — and even the Obama administration — will be trained on the Motor City.

The primary’s crowded field of candidates, 15 in all, seems to underscore the gravity of its ultimate outcome. However, the typical off-year election turnout for an August primary belies its importance.

From 1978 through 2010, Michigan’s statewide voter participation during non-presidential primaries has averaged about 19 percent, according to statistics from the Secretary of State’s office.

Detroit’s average is even less. According the City Clerk’s office, the last mayoral primary, in August 2009, saw less than 98,000 total votes cast — out of 575,000-plus registered voters. That’s barely 17 percent. Looked at another way, less than two out of every 10 registered voters in Detroit has the power to set the terms of an electoral race for the city’s most important position.

Is voter apathy so pervasive that only a fraction of the city’s voters can be bothered to participate in their own fate or are other elements conspiring against the opportunity for self-determination?

“There is so much confusion out there people are that people are befuddled,” explains political analyst Bill Ballenger, editor and publisher of Inside Michigan Politics. “ The Emergency Financial Manager casts such a giant shadow that people are turned off and confused.”

Yet, that confusion can only explain so much. Ballenger also pointed out the glaring difference that four years can make examining the number of candidates for city council.

“Four years ago, there were 160 candidates running for at-large seats on the Detroit City Council,” Ballenger says. “This time around, there are only 55, which is pretty pathetic.”

Pathetic as it may be, perhaps it’s endemic of a larger issue, which is the rapid deterioration of the city’s overall wellbeing — from its infrastructure to its finances?

When your cultural institutions are under threat of liquidation to satisfy creditors, and you feel under siege by not only the criminals who roam darkened nighttime streets with impunity, but your own state government, it seems natural that people would not want to undertake the herculean task of running city government. Especially when, as it stands, that governance involves more kabuki dance then policymaking.

Given the fact that the new mayor and City Council members will have virtually no real authority when they take office next January, essentially serving at the pleasure of Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr, one of the overarching questions facing voters is: Why bother casting a ballot at all?

There are a number of ways to answer that question. One is to look at this election as a referendum of sorts. If you believe the state’s emergency manager law is legal, and that Gov. Rick Snyder’s appointment of an outsider to take control of city operations was a necessary to address its financial crisis, then supporting candidates who share that view is a way to buttress that viewpoint.

If, on the other hand, you see the appointment of an emergency financial manager as illegal and anti-democratic, there are candidates promising to support the legal fight to have the law overturned.

Moreover, the term of the emergency manager is limited to just 18 months. If Orr is to be believed, he intends to have the city returned to solvency by then. Of course, that could change, especially now since restructuring of the city’s debt is in the hands of the federal courts. However, if the original timetable remains accurate and the reigns of governance will be returned to the city’s elected leaders before next year ends, then it very much matters who is selected at the polls this year.

Because, even if the emergency manager is successful navigating the city through bankruptcy, the books become balanced and the burden of crushing debt is made lighter, the city’s problems won’t have vanished.

Addressing blight, ensuring public safety and finding ways to halt the exodus of countless residents from disparate and beleaguered neighborhoods will remain issues facing whoever is presiding along Jefferson Avenue once the emergency manager leaves.

So this election remains vitally important.

These are strange times indeed. Detroit has become the largest municipality in U.S. history to seek Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection while an unelected leader is currently calling the shots.

Little about the governance is certain at this point.

What is clear, though, is the right to have your voice heard at the ballot box has not been taken away, and there are a handful of candidates prepared to take on the thankless task of course-correcting a ship that listed for six decades before running aground. This election is anything but meaningless.

Check out each of the interviews: