Meanwhile, in many quarters of the city, an unsympathetic occupation by inexperienced, trigger-happy soldiers ensued. News reports talked of "snipers," and tanks rolled down main streets.

Charles Simmons: I remember going down on 12th Street and I ran into a guy who I knew who was a hustler. He had gone into a jewelry store or pawn shop and stole a lot of jewelry. He had all kinds of bling, and the National Guardsman, the soldier, was standing right there while I was talking to him. They didn't know what was going on.

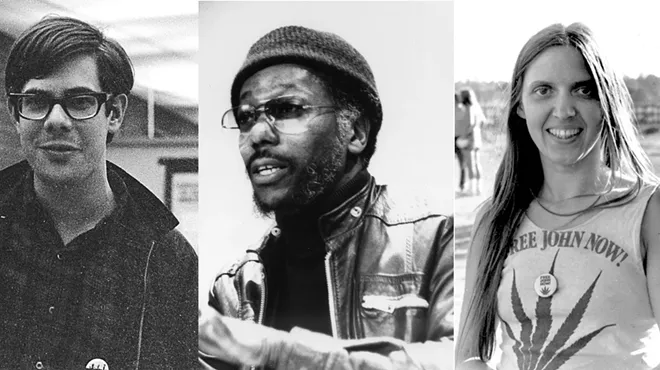

Peter Werbe: All the hostility I saw, with numerous incidents personally, was threats to me from National Guardsmen and the cops. One of the bivouacs was at Central High School, and we rolled up there. This guy sees these two white guys, and says, "Can I help you?" And I said, "Yeah, we're from the Fifth Estate." And he raises his Garand and says, "I know who you are. Get the fuck out of here!"

Herb Boyd: You had this feeling that obviously it's an occupying army and the best thing, my mother told me very well, as she learned in 1943: Take cover. Go in, cut off your lights, and get down, because there's a certain madness out there. You flick the light in your apartment and suddenly they start shooting at the apartment building, scattering bullets all over the place.

Harvey Ovshinsky: And then coming home to hide under our beds because the tanks are rolling down our street, and you daren't light a cigarette, or turn on a flashlight, or attract any attention because there were reports of snipers everywhere. ... Yeah, the war came home — and we were in it.

John Sinclair: And then they had the National Guard coming down the street. Whew. That's pretty severe. I'd never seen anything like that in my life. What? A tank? On Warren Avenue? Are you nuts?

Peter Werbe: One morning, we were in a friend's apartment on Jefferson and Rivard. Why were we smoking dope in the middle of the day? Probably just because we had it. And someone says, "Wow. Look what's rolling down Jefferson." And we look out the window at personnel carriers and go, "Whoa."

Frank Joyce: Now, everybody says this, but I have to say, there is something about just seeing tanks rolling down the streets of your city that is powerful.

Peter Werbe: My wife Marilyn and I lived on Third and Delaware. After we'd gone to sleep, we heard some commotion outside at like 3 in the morning. We look outside, and this National Guard contingent in front of a Jeep has this black man spread eagle on his face wearing just a tank top and boxer shorts. I have no idea where he came from or why he was there or anything, and they're all yelling and nervous as hell, pivoting around, pointing their guns everywhere, and there was nobody on the street — at all. And they were yelling at this guy, and I said to Marilyn, while we were crouching down by this window, I said, "Those sonofabitches."

And I didn't realize on this carport right below us there was a guardsman and he turns around. I guess I'm lucky I didn't get my head blown off. He said, "Get down!" and Marilyn and I both froze, and I remember he put the bayonet — they had fucking bayonets — and pushed it against the screen and said, "I said, 'Get down.'" And I just took Marilyn and just pushed her head down and we just lay there. And I remember they got in their Jeep and they went. I don't know what happened to the guy.

Marilyn said, "Can we get up?" And I said, "Let's just wait a minute or two."

Frank Joyce: It was already known on the street, meaning in the black community, that the police, and the military, and the National Guard in particular were out of control. That they were randomly both arresting people, shooting people and killing people.

Harvey Ovshinsky: In our very earliest reporting, we took for granted that it was the rioters who were doing the sniping and the shooting. We didn't find out until later, with our investigative reports and from elsewhere, that a lot of the shootings were done by the National Guard.

Frank Joyce: I don't think there were any snipers. If there were any, it was like one or two people. And not necessarily because they were part of any political group, but simply because then, as now, we're a weaponized country.

‘I’d never seen anything like that in my life. What? A tank? On Warren Avenue? Are you nuts?’

tweet this

Herb Boyd: They were talking about [how] there was some kind of armed resistance. Well, you might have one or two that may have fired back at the National Guard, but there was never a concerted effort in that direction because it would have been absolutely suicidal.

Peter Werbe: The Detroit News and The Detroit Free Press were essentially just bullhorns for whatever the established powers in Detroit wanted to see in print.

Harvey Ovshinsky: I remember it felt like they were getting it wrong because they were focusing on what was obvious. It didn't feel like they were on the ground. You have to understand, in those days, the black community was pretty much invisible. Unless you were in trouble or arrested, young people and black people were mostly invisible to the media. And women, forget about it: They were quarantined to the society section.

Frank Joyce: I wrote a front-page piece for the Fifth Estate called, "Who killed John Leroy?" Leroy was shot in cold blood by, I believe, a National Guardsman. We were really reporting on the rebellion from the point of view not of what the rebels were doing, but what the authorities were doing.

Peter Werbe: Frank Joyce found out that a carload of black men coming home from their jobs were stopped at a National Guard checkpoint, these frightened young white guys from Escanaba. Who knows — maybe somebody made a sudden move. And these guys just shot up the car, killed a man named John Leroy, and severely maimed somebody else. I thought this was pretty deep investigative reporting that nobody did about the riot dead in Detroit until a few years after that.

Harvey Ovshinsky: We really rose to the occasion. It really tested our skills as journalists. The paper demanded that we not cover it but uncover it. And obviously the Michigan Chronicle did too. And I'm sure there was some fine reporting done at the News and Free Press; I just can't speak to it. Because their sources were mainly in the police. We had different sources. Who were we going to call?

Frank Joyce: I recall having a sense that there's going to be hell to pay for this, there's going to be a backlash for this, and just this physical destruction is going to have profound and difficult effects for the city and the people who live in it. It was sobering in that way. I do remember saying, "Hmm, maybe this isn't the whole romantic thing we imagined."

John Sinclair: After the National Guard and Regular Army troops had established control of the streets and stopped the fires, they just started picking up people, getting them off the streets. At least 4,000 people were arrested. And most were arrested just for being out after 8. People of every kind got swept up. If you went to the store after 3 p.m., you didn't get home, you know?

Herb Boyd: It was a very nervous time for a lot of our friends who were taken out to Belle Isle, getting brought into night court where Judge Crockett was letting them go left and right.

Charles Simmons: When you look at who got locked up, I'm sure some white people got arrested, but it was mostly black people. And the houses that got burned were our own houses.

Leni Sinclair: We had to leave. We gathered a few people and went to Traverse City for refuge, because we didn't know what was going to happen. It was very scary after the National Guard took over the city. It was like war, with tanks driving down the street, and we had to escape.

John Sinclair: We fled to Ann Arbor in '68 because of the street-level relations between the hippies and the police. Because after the riot, the police were really in charge then, and we just had to get out of there. We thought, "Ann Arbor? They've got like 10 police cars."

Frank Joyce: I wrote one thing in early '68 that was about the repressive response that was coming. The City Council passed a bond issue so they could buy machine guns and armed personnel carriers. There was a transition from the Big Four to the Tactical Mobile Unit. That was, in turn, followed by STRESS.

Charles Simmons: What I remember most was that the attitude of the people had changed so radically. There had been this fear of police. And that vanished after that week. And the idea of racial pride and black pride in general, and identification with African and African-American culture, there was an explosion of it — suddenly. After '67, immediately you saw people identifying themselves culturally with the dress, the attitude, and the pride, that all spread immediately after the rebellion.

Herb Boyd: The '67 rebellion kind of fueled our struggle at Wayne State University. We could put pressure on Wayne State University because they were so fearful that possibly we would have another eruption. So we created the Association of Black Students.

Charles Simmons: I wanted to be a journalist. But when I had applied for jobs as a student in Detroit, they basically laughed at me. All of a sudden, they wanted us to come in. Well, one reason was that white reporters were not allowed into the hood because of the rebellion. They would chase them out. So they had to hire people of color to go in and do interviews and stuff in the midst of all the fires and people getting shot. [laughs]

Pun Plamondon: I wouldn't say it improved things, but it definitely changed things. There's more black cops on the force, though I hope everyone quickly learned cops are cops — it doesn't matter the color of your skin.

Charles Simmons: We said we wanted black people on the board of directors, we wanted black foremen, we wanted black people as secretaries and all that. Well, they did all that. But that didn't change the nature of the exploitation of the system that continues to rip us off. We saw the face of the exploitation change its color.

Reggie Carter: Even when you have the ascendancy of Coleman Young in '73, a black mayor, and a significant black presence on City Council, and suddenly you get black judges, and so on, in the long term we've seen how meaningless that can be. Because what happens is you get a black mayor on one side of the coin and then you get disinvestment on the other side of the coin.

Harvey Ovshinsky: It was exciting. But in retrospect, it's only worth exploring, investigating, and remembering if you learn from it. If people are just commemorating and having exhibitions and writing articles and books, and the intention is just to recall it and remember it, then I think an opportunity is wasted. I think we have to try to learn from it and understand it and make sure it doesn't have to happen again. It had to happen. It had to happen. Make sure it doesn't have to happen again.

Leni Sinclair: The rebellion was a wake-up call. But you know, people never woke up. [laughs]