Police surveillance as a concept can be difficult to wrap one's mind around. Since it's about the collection and flow of information, it feels intangible and conceptual, even as the physical manifestation of surveillance — from the cameras in convenience stores to the lenses attached to cops' uniforms — has become so ubiquitous it's almost invisible. Yet, the very real impact of surveillance abuse is felt most brutally by our most disadvantaged populations, particularly Black communities.

It can help to think of police surveillance as a kind of nervous system belonging to a monstrous organism. The cameras installed throughout Detroit as part of Project Green Light are the eyes, ears, nose, and fingertips of law enforcement. These devices send back the information to a brain, if you will. In Detroit's case, its never-sleeping surveillance brain is the Detroit Real-Time Crime Center.

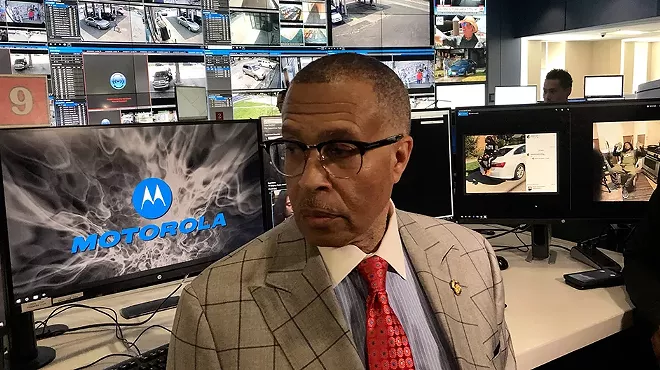

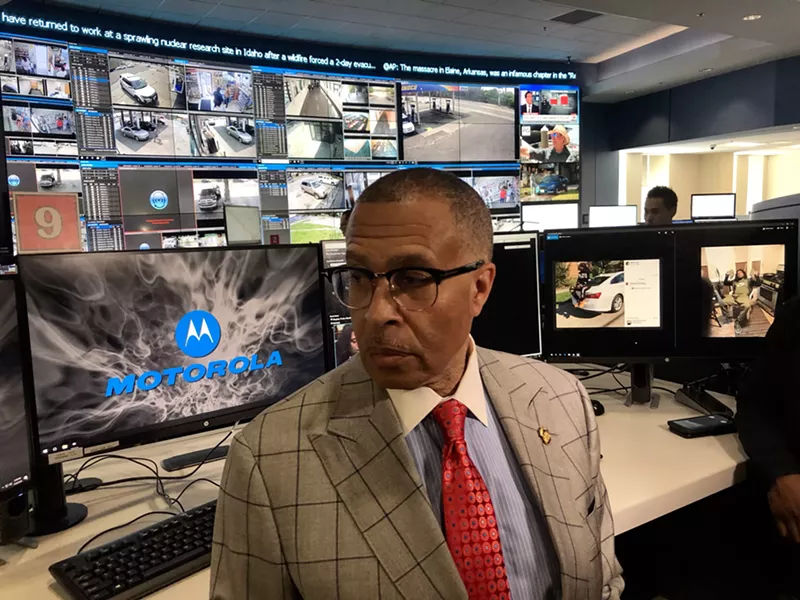

Imagine a high-tech crime TV show or movie from the 1990s, with a room full of futurist cops and analysts sitting as computer workstations, their faces underlit with the glow of algorithms and numbers, while a wall of TV screens display live video surveillance footage, overlayed with digital enhancements. This is how RTCCs look, almost as if the companies selling these systems are getting their ideas from Hollywood. Detroit's is growing quickly. In the beginning, police described it as "very small, very close-quarters" with just a couple computer monitors. In 2019, police began expanding it to a 9,000-square-foot command center with two satellite stations.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for civil liberties in the digital age, has worked with undergraduate journalism students at the University of Nevada, Reno's Reynolds School of Journalism over the last 18 months to document the acquisition of surveillance equipment and software by police and sheriff's offices across the country. As of our July 2020 launch, the Atlas of Surveillance contains more than 5,300 datapoints from more than 3,000 law enforcement agencies. Users can use the map or a searchable database to discover what agencies have which technologies.

The Detroit area emerged as a hotspot on our map, with DPD and other Wayne County law enforcement deploying drones, body-worn cameras, automated license plate readers, face recognition and signing partnerships with the company that makes Ring cameras and the Neighbors app. DPD was also one of about 60 agencies nationwide (from New York City to Ogden, Utah) that have developed the RTCC model of surveillance.

An RTCC is generally characterized as a central command center with access to a combination of technologies, such as live cameras feeds, automated license plate readers, gunshot detection, social media monitoring, predictive policing software, and access to a variety of criminal justice and commercial information databases. They are similar to "fusion centers," but differ in that RTCCs are operated locally, whereas fusion centers are generally at the state level and part of a nationwide U.S. Department of Homeland Security information-sharing program.

In an age where protesters are chanting "Defund the Police," it's important to note that surveillance isn't just invasive, it's also costly. Detroit's RTCC program has cost in excess of $12 million. And often, when budgets shrink, surveillance is the first go. In California where EFF is based, the Fresno Police Department closed its real-time crime center at the beginning of the year, and the Sacramento County Sheriff's Office shut down its gunshot-detection program citing budget cuts.

Here's what you need to know about Detroit's RTCC program.

Back Story

Detroit's 9,000-square-foot RTCC was launched in 2016 at an initial cost of $8 million, funded by municipal bonds, followed by a $4 million expansion in the summer of 2019, which included the creation of two smaller satellite real-time crime centers. The RTCC is intrinsically linked to DPD's controversial "Project Green Light" video camera and a related facial-recognition program, which was announced in January 2016 as a countermeasure against Detroit's violent crime problem.

Outside the Real-Time Crime Center

One of the signature features of the RTCC is live access to cameras throughout the city: more than 6,000 feeds as of March 2019.

One of the primary sources of video is "Project Green Light," a program that asks businesses to install cameras at an angle where they can capture license plates and accompany them with green-colored light to signal their involvement in the project. As the Detroit Community Technology Project explained in a June 2019 report, the "Project Green Light" program began in 2016 with cameras at eight gas stations and has since grown to a network of more than 550 locations, including schools, churches, and health centers.

Those aren't the only cameras feeding data into the RTCC: As of fall 2019, DPD had installed automated license plate readers at various traffic intersections. This technology involves cameras that photograph license plates, tag with GPS coordinates and time and date, and uploads the information to a searchable database. This allows cops to search the travel patterns of vehicles and even get alerts on a vehicle's location in real-time. In August 2019, the city approved a plan to install an additional 500 video cameras at intersections as part of a "Neighborhood Real-Time Intelligence Program." According to local TV station WXYZ, there are also "secret, hidden cameras" in various areas where illegal dumping is common.

In 2019, the city approved a $4 million expansion of the RTCC program, half of which went to the creation of two 900-square-foot "mini" RTCCs within the 8th and 9th precinct buildings on the west and east sides of the city.

Inside the Real-Time Crime Center

As of 2017, the RTCC had 60 staff members, one-third sworn officers and two-thirds unsworn personnel, but DPD planned to add 21 more "crime analysts, video surveillance analysts and intelligence specialists" as part of the 2019 expansion.

Like many RTCCs around the country, the Detroit RTCC is readily identifiable by the 32-by-9-foot video wall that allows staff to watch footage in real-time. DPD has integrated these video feeds into CommandCentral Aware, a software suite for "real-time video surveillance and data analysis" sold by Motorola Solutions. In addition to a variety of crime and intelligence databases, analysts also monitor social media and news feeds and run background checks on suspects.

The RTCC also provides space for Detroit Public Works employees, who monitor 121 cameras mounted on 787 smart traffic lights that were installed in 2019. The cameras "collect data, such as the volume of vehicles and pedestrians who are going through these intersections," the public works director told The Detroit News.

Probably the most controversial aspect of the RTCC is its use of facial recognition software to identify individuals caught on camera using an automated algorithm. DPD contracts with DataWorks Plus, one of the primary vendors providing biometric technology to law enforcement agencies. Similar to fingerprint comparison, facial recognition works by measuring certain elements of a person's face to create a template, which is then compared against other templates culled from an image pool, such as a mugshot database.

In light of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, protesters in Detroit have called for the abolishment of facial recognition, amid reports that innocent people have been misidentified by the technology and police chief James Craig disclosing that the software makes errors "96% of the time." In January, Robert Williams was arrested at his home in Farmington Hills, accused of stealing watches from Shinola; DPD officers later admitted their computers misidentified him. Last year, Michael Oliver was incorrectly charged with felony larceny for an incident in which a man stole a teacher's cellphone; those charges were also dropped when Oliver's attorney proved DPD's computers identified the wrong man.

Residents advised City Council not to extend its $219,000 facial recognition contract, which was set to expire last month. The contract did expire; however, DataWorks will continue to provide support until the end of September. After that, DPD can continue to use the software but will have to maintain it internally.

University of Nevada, Reno, Reynolds School of Journalism Students Matthew King, Hunter Drost, and Hailey Rodis contributed to this report.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.