As we approach the 40th anniversary of the disco craze, it’s cause for a bit of mixed feelings. That’s because I was taught to hate and make fun of disco. But before I was taught to ridicule zodiac jewelry and leisure suits, I actually liked disco — or what I heard of it — back when I was a 7-year-old wallflower (at least during the slow songs).

Most of that contact with disco was — like other Americans — thanks to the film Saturday Night Fever, which was released 40 years ago last week. Almost overnight, every household seemed to have the double-album soundtrack crowded with hits, many by the Bee Gees.

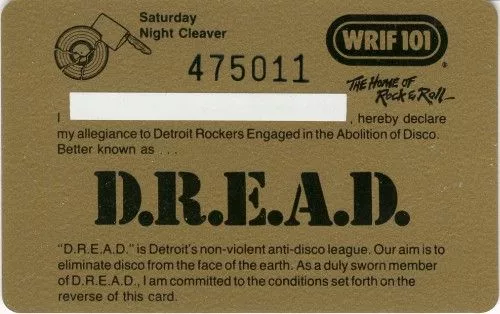

Yes, within a few years, my friends and I would be making fun of “John Revolting,” his white three-piece, and lit-up disco floors, and scrawling our names on the back of our D.R.E.A.D. cards — "Detroit Rockers Engaged in the Abolition of Disco." Those cards were a gimmick thought up by the deejays at WRIF 101 FM, and “members” promised not to wear platform shoes or listen to disco radio stations, among other heresies.

That’s significant, because some cultural music writers have charted the political contours of early disco — the queerness and blackness of it — and the white hetero backlash it prompted. For instance, Peter Shapiro’s book, Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco, called disco “a shotgun marriage between a newly out and proud gay sexuality and the first generation of post-civil rights African Americans, all to the serenade of the recently developed synthesizer.”

In truth, WRIF 101 did play disco tracks when they got popular enough, and, unless memory fails, stayed at least arm’s length from some of the most outrageous white rocker backlash against disco, such as the “Disco Demolition” riot at Chicago’s Comiskey Park on July 12, 1979, touched off when hundreds of disco records were shredded in a massive explosion on the playing field.

No, even big bad WRIF would play big disco hits like “Stayin’ Alive” in the winter of 1977 and 1978. But “white rock” and “black soul” were generally on different stations, and white music in general was still pretty square. We're talking about a time when square Anglo-Saxon crooners like Debbie Boone and Karen Carpenter were scoring No. 1 hits.

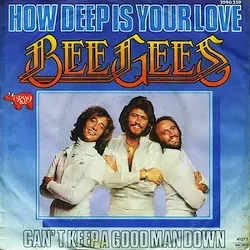

What rose to challenge that musical segregation were the Bee Gees tracks we’d probably file under “easy listening” today. The most popular was the slow-dancing butt-cupper “How Deep is Your Love,” which had been released as a single in the United States in September, but by December had soared to the top. On Christmas Eve, 1977, “How Deep is Your Love” became the No. 1 song on the Billboard Hot 100 — aptly knocking Debbie Boone’s “You Light Up My Life” out of the top spot — and remaining in the Top 10 for a record-breaking 17 weeks, literally until April flowered.

It was a drama I remember watching all winter and spring, little realizing how special it was to a native Detroiter like myself. Every weekend, Casey Kasem, the most famous deejay in the country (originally born in Detroit as Kemal Amen Kasem) would document how that hit hovered as though weightless near the top of the charts, buoyed by its canny utilization of honeyed harmonies crooned in a distinctly Motown style. Despite the breathy British accents, this was black music as homegrown as Berry Gordy Jr.: It showed through in the deep production values that sounded terrific in a car, the cascading notes shimmering out of the synthesizer, the Eddie Kendricks-style falsetto cries.

Today’s critics might be more disposed to decry the song as an example of cultural appropriation. Some of those criticisms were even voiced at the time. But for the Bee Gees, it was obviously a love letter to the artists they valued most. As Robin Gibb himself had said, “The Bee Gees were always heavily influenced by black music … and soul has always been my favorite genre.”

Is it wrong to look back 40 years and feel grateful to the Bee Gees because they put black music where white ears could hear it and groove to it? Disco had at most a year or two to bend white listeners’ ears before the largely segregated charts of the Reagan era ensued with a vengeance.

Thankfully, I was eventually curious enough to stop giggling about the clothes and the trappings of disco, to try to find the other more authentic music that lay behind the fad I had known. Finally, like Robin, Maurice, and Barry, I fell in love with the music that inspired them. Who knows? Maybe it wouldn’t have happened without that brief moment when even a tow-headed kid living in the suburbs learned to slow-dance a little more soulfully.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]