The triumph of We Came As Romans

Following the death of singer Kyle Pavone, the Michigan band presses on by tapping into the hope its members had when it first started

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

We Came As Romans was on the brink of collapse.

“We almost broke up,” drummer David Puckett tells Metro Times. “We didn’t know what to do."

The Troy-based metalcore band was prepping for what was supposed to be its comeback tour when tragedy struck: Singer Kyle Pavone was found unconscious following an accidental heroin overdose.

On Aug. 25, 2018, six angry kids from the suburbs became five, and music lost another voice before his time. Pavone was 28. Hope has been one of the band’s core tenets since forming in the mid-aughts. But at that moment, it was impossible to find.

Suddenly the Myspace success story with a decade of countless sold-out shows across five continents, hundreds of millions of streams online, and impact beyond its members’ wildest teenage dreams was forced to reckon with Real Shit: the loss of a brother.

“Not only have you lost your best friend,” guitarist Lou Cotton says, “as that starts to settle you’ve gotta think of, ‘what are we gonna do as a business and for our careers?’”

More than four years and countless therapy sessions later, the band is in a much different place. There are lots of analogies for grief. For guitarist Josh Moore, it’s like being trapped out to sea at night, somehow trying to navigate the tidal waves of anger, anxiety, sorrow, and regret as a tropical storm bears down.

“At first it’s just figuring out a way to weather that,” Moore says. “Figuring out a way to continue to push forward so I’m not just here in this rut.”

The band made the decision not to replace Pavone, who handled clean singing alongside co-vocalist Dave Stephens’s guttural screams. They felt it would be impossible to find someone with his distinct combination of voice, charisma, and chaos. Instead, Stephens would carry out all vocal duties for the band, strengthening its foundation instead of filling a void. He, Moore, and bassist Andy Glass have been working with a voice coach to increase their range and versatility.

And so WCAR persevered, at least musically. Since that tragic August morning, they’ve played over 400 shows — proof that in their darkest moments, fans were willing to persevere alongside the band.

I catch up with WCAR as the band heads into pre-tour rehearsals supporting its first record since Pavone’s passing, last October’s Darkbloom. Following a 72-day run last year that concluded with a pair of hometown album release shows at The Loving Touch, the band has been home enjoying the fruits of its labor. Spirits are high, but after this much time off, there were some jitters.

The current tour is the band’s biggest yet. Video screens with music-synced motion graphics have replaced their usual stage banners, and they’ll be headlining some of the largest rooms of their careers on a three-band bill — culminating with a stop at Saint Andrew’s Hall this Saturday. Night after night WCAR will exorcize demons, playing cathartic songs about their late frontman to a fanbase nostalgic for material Pavone himself performed.

That vulnerability could be a huge risk.

In 2008, six teens from Troy took a leap of faith. A majority of the members of the band were in their first two years of college, with Pavone and founding drummer Eric Choi still in high school, and soon WCAR built a dedicated local fanbase playing loud, noisy music at least three weekends a month. They played churches, a Days Inn in Hazel Park, and 200-seat rooms, like the Hayloft in Mount Clemens, often squeezed onto seven-band bills. But the band’s work ethic, pop sensibilities, and fan outreach helped WCAR stand out in the late-aughts Myspace metalcore scene.

Glass’s art direction capitalizing on the band’s boyish good looks didn’t hurt either. Looking at their old profile via the Internet Archive is like a time machine back to Somerset Mall circa President Barack Obama’s first term: gauged ears, foppish hair with shaggy bangs angled over one eye just so, and pyramid-studded belts holding up women’s skinny jeans. You can almost smell the Got2B Glued hairspray holding it all together.

Between Choi’s high school graduation money and scratch from odd jobs, the band had enough funds to record the aptly titled four-song Dreams EP. Produced by Joey Sturgis (The Devil Wears Prada, Asking Alexandria) and recorded in Sturgis’s friend’s garage, it gave the band something to shop around to labels and give away to fans online.

Even before sending out Dreams, the band members knew straddling school and the music biz would soon be untenable. If WCAR wasn’t going anywhere by year’s end, the plan was to break up and get their diplomas. But to hear Moore tell it, no one really planned to finish school. He was on a full-ride academic scholarship at Oakland University with no skin in the game. They were going to make this work.

Pavone was already on the verge of dropping out of Seaholm High, though. He was a born singer, with perfect pitch and a knack for rearranging chord progressions in his head. Kyle could sing along to any pop song in the car and hit every note. (That’s likely why WCAR’s cover of U.K. club banger “Glad You Came” by The Wanted is the most popular of their top 10 songs on Spotify.)

Conner Pavone shares stories about his older brother, sitting across from me at Java Hutt. Even at 6 feet 2 inches tall with a lacrosse player’s shoulders, Conner still looks enough like his lanky, but shorter big brother that I did a double take when he walked into the coffeehouse for our interview.

After WCAR was signed, Conner says, their parents invested in his voice and sent him to lessons with heavy metal vocal coach Melissa Cross. Kyle was primarily a tenor, but learned to stretch to restrained falsettos and a deep low-end.

The family knew Kyle was destined for stardom given his showmanship and pipes. Balancing his talent and behavior at home was another matter. Conner says things were always tumultuous between his parents and brother. Kyle partied hard.

As an outsider, Kyle fell in with others like him. And with that came sex, weed, booze, and malicious destruction of property. He wouldn’t come home for days at a time because, well, a cell phone confiscated for bad behavior meant no one could bug him about curfew. By his junior year, the Pavones had enough and kicked Kyle out.

“Being a rockstar before you’re in a band has its grievances with your family,” the younger Pavone says.

Conner recalls pleading with Kyle to take the ACT test. He even entertained the idea of taking it for his troubled sibling. Conner was a sophomore and still a skeleton back then. He could’ve easily passed for Kyle if need be. Neither of them had studied, but college wasn’t optional for either of them. Conner saw an incredulous Kyle walk into school four hours late on testing day, and again stressed how important the ACT was to his dismissive brother. Half an hour later, Conner spotted Kyle walking out the door. He took the test, sure. But he also marked B for every answer.

“He got the points for writing his name correctly,” Conner says. “I don’t think he ever went back to high school after that.”

Around the same time, WCAR’s original singer had exited and the band needed a fill-in. After a brief try-out tour, Kyle was hooked. When Glass visited the Pavones to talk them into letting his friend pursue touring full-time, they had no idea he’d already quit school.

Conner says his family wasn’t particularly religious, but was willing to try anything to get Kyle on track. Glass used that as a tool, telling Kyle’s parents that WCAR was a Christian band.

The band had its ties to spirituality. However, it never was explicitly religious. Prior to WCAR, Moore played in a band at church. Glass’s parents were missionaries, taking him to India when he was 4. Themes like hope, love, and brotherhood run through the band’s lyrics, but WCAR was keen to not put themselves in a box. It's about inclusion for them.

“They wanted to give people hope because some of the guys [as teens] didn’t feel like they had it,” Puckett says. He joined the band in 2016 after Choi amicably parted ways, and had toured with WCAR in his previous band, For Today. “They wanted to be that beacon.”

The Venn diagram of heavy music and hopeful messages is incredibly tiny. It’s a sincerity that, almost 20 years later, still helps WCAR stand out.

Scroll down the YouTube comments on the band’s music videos and amid countless memorials for Pavone you’ll find almost as many missives saying how a given song helped someone through the loss of a loved one or a tough breakup.

The same can be said for lots of bands, sure, but WCAR's fans take it to another level, and the band has noticed.

"It adds more fuel to the fire,” Glass says.

And besides, not everyone in the band is Christian. They all love tattoos and partying — preaching religion from the stage would be hypocritical.

One last thing about WCAR’s Myspace page: It’s also a time-capsule of those early years of the grind. Struggling to scrap together the $50 per month each member paid to cover a van payment, gas, and insurance. Stretching $2 per day for food. (“It was your job to come up with the $0.12 tax,” Moore says.) Sleeping six guys in a Chevy Astro van because even if they dropped $60 of their nightly $70 payout on a crappy hotel, only half would be allowed in.

A lack of willing auto-loan co-signers limited buying options to junkyard-bound deathtraps. In 2009, the band toured coast to coast and back with nary a night off in four months. WCAR burned through three vans during those early years — quite literally.

They’d just replaced the transmission in their second van and were in Cincinnati when the dashboard suddenly caught fire, melting the wiring harness before an overnight drive to a show in New Jersey. The guys stuck spray-painted tap lights to the trailer, wired the headlamps directly to the battery somehow, and drove all night in a cabin that reeked of acrid, oily electrical smoke.

That cross-country drive would be a catalyst for the rest of their career. Selling out a 200-seat room in Michigan was one thing. But doing it in a larger market in front of a label? That night, WCAR picked up an agent and met their managers for the first time.

“That was a huge stepping stone,” Stephens tells me.

Dreams got immediate attention from labels, but the band held out until an offer came in from Equal Vision Records. Moore naively thought that since the band Chiodos was based out of Michigan, had signed with Equal Vision, and sold hundreds of thousands of albums, by the same virtue WCAR could copy their homework, change it a little bit, and profit.

“Of course, because that’s just how it works,” he says with a wry laugh.

“They wanted to give people hope because some of the guys [as teens] didn’t feel like they had it,” Puckett says.

tweet this

On a long enough timeline, every band will drop a divisive album. In WCAR’s case, it’s their 2015 self-titled fourth record.

“They did what they set out to do at a larger scale than they ever could have imagined” with the first three albums, Puckett says on his drive north from Ohio for rehearsals. “And then they kind of lost that vision.”

WCAR enlisted producer Dave Bendeth (SR-71, Paramore) and came away with an album that the band fell out of love with almost before it even hit the shelves. Fan response was similar.

“It was us trying a bunch of weird shit and not knowing where we wanted to go,” Stephens tells me.

Moore says behind the scenes, the band got pulled in lots of directions by people with the mindset of “your resume looks like shit compared to mine, so you’re going to do what I say.” Moore, the primary songwriter, says there are a few good standalone tracks on the album. But as a cohesive statement?

“It’s a straight turd,” Moore says. “I started in this band when I was 15, I’m 30 now. I’ll know a stinker of a song when I hear one.”

We Came As Romans debuted 11th on the Billboard 200 before dropping off the chart within two weeks. The album relied on syrupy hooks and eschewed the synths and deeper lyrics WCAR was known for. What works for Top 40 doesn’t work for metalcore. If you’re not writing music you believe in, your fans see right through it, Stephens says.

Merch, tickets, and music sales all took a dive. Offers for support slots dried up. After a decade of relentless work, it was looking grim. “To have it fall apart so quickly was heartbreaking,” Stephens says.

“We were witnessing the decline of our band in real-time,” Moore says. “I think a lot of the industry had lost faith in us … we lost a little faith in ourselves.”

Not everyone was as affected by the album’s reception. Pavone and his brother were roommates, and days before he passed, the self-titled record came up. According to Conner , Pavone said the album needed to happen given their success, saying, “We had to put out a shitty record, because now it brings us back to Earth.”

Cold Like War, the band’s 2017 SharpTone Records debut, was a return to form. WCAR just had to go through a full-blown identity crisis to get there first. Following its previous album the band was rudderless, unsure of what to say or how to sound. Producers Drew Fulk (Motionless in White, Beartooth) and Nick Sampson (Miss May I) reached out to WCAR fans on Facebook and asked what they missed about the band.

The band took the feedback and ran with it, reintroducing synths, drum machines, and bigger riffs. They also played up the dynamics between Pavone’s soaring clean vocals and Stephens’s bowel-shaking screams.

An offer to support Michigan-based I Prevail on tour came in, and kept the band busy for 50 nights between September and December. This critically put them on the road during Cold’s October release window. Fans ate up the new material and its sincere — but still crushingly heavy — reflections on heartache, the band’s career thus far, and staying true to yourself.

“When our backs are to the wall we’ll come out swinging,” Glass says.

The next month they announced a headlining tour that would end early April in Grand Rapids after a stop at The Crofoot Ballroom the night prior.

It was spring 2018 and slowly, WCAR was clawing their way out of the hole.

The number of bands who’ve successfully replaced a singer is incredibly small. So rather than try, WCAR forged ahead without Pavone. Weeks after laying their fallen brother to rest, the band headed out on tour supporting Bullet for My Valentine as scheduled.

Stephens acknowledges that singing Pavone’s parts would be weird, both for fans and his bandmates. Given the alternative, he thought it was the right choice.

“I can’t imagine how much more strange it would be to have someone else singing them permanently,” he told Kerrang in 2019. “To celebrate Kyle’s memory and legacy with our music, we had to have the rest of the band pulling together to go forward. It was about making the best of our situation.”

Pushing through the pain every night with each other and their fans wasn’t an easy choice. Versus laying in bed all day with the shades drawn, lights off, and a bottle of gin, though, it was the healthier option.

“You don’t know where you’re going to get [mentally] staying in that environment and letting the spiral keep happening,” Moore says.

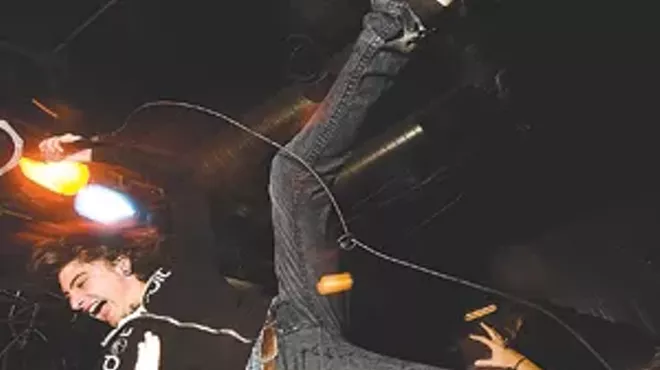

The idea was, regardless of how hard it was to keep their heads above the waves of grief, they’d come out stronger if they went through it together. YouTube clips of those shows are a stark contrast to every other tour from the previous decade. There was no stage-diving off amps. The exuberant smiles from the sheer joy of realizing a high-school fantasy were gone.

“I’m standing in place crying and I’m head down, playing my guitar,” Moore says. “It was literally all my suffering on display every day.”

WCAR barely made it through those sets. Facing an existential tragedy, how do you press on? At least once a week someone wanted to stop the tour and go home. But each show got a little easier, with the band members consoling one another and doing regular check-ins to see how they were feeling, encouraging each other to push on because they’d worked so hard to get this far and Pavone would be pissed if they gave up now.

Facing an existential tragedy, how do you press on?

tweet this

MusiCares, a non-profit support network tied to the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, reached out to the band, giving them grants for therapy and helping them find counselors. All but one member took the offer, and several are still in treatment. You can hear the help the organization provided throughout Darkbloom, the band’s first album without Pavone’s direct input. He may not have been with the band physically during the writing and recording process, but his spirit was guiding it the entire way.

When it came time to record, the band scrapped some 30 morose demos after Glass says he had an unexpected visitor during a Reiki meditation session. He says he felt Pavone reaching out through the Reiki practitioner to send him a message, saying, “If you have to suffer to create music because of me, then you didn’t really know me.” It was an eerie moment – Glass hadn’t told the practitioner the band was headed into the studio or working on a new album.

Darkbloom might be the band’s most personal work yet, a raw, crushing 36-minute examination of the seven stages of grief and a forthright refusal to let the loss of a beloved frontman destroy WCAR’s future. “You can write about the stuff that sucks,” Stephens says, “and you can also write about how you got through it.”

The album also makes up a bulk of WCAR’s set for this tour, with the band playing nine of those ten songs every night when fans might want to hear more classics off the first three albums instead.

Two years ago the band retired material from its first full-length — 2009’s To Plant a Seed — from live play largely in part because those songs were written in high school and the band didn’t identify with them as much anymore. Given what they’ve been through, WCAR needs to play Darkbloom live.

The late singer’s legacy lives on in the Kyle Pavone Foundation, which provides Narcan, Fentanyl test strips, and overdose training for production crews at festivals. It’s run by Conner and his parents.

During the COVID lockdown they partnered with the Battle Creek Community Foundation for the Kyle Cares Scholarship, paying out $2,000 grants for musicians in need of help with mental and physical health, substance abuse treatment, food, and housing. Of the 85 applicants so far, none were refused.

It lives on in stories. Pavone was the guy who’d slur his way through a Blink-182 medley on his birthday at a Danish karaoke bar before telling the crowd “you’re welcome” and dropping the mic. He’d pierce your lip behind a barn at church camp with an earring, and without ice.

It lives on in pre-show rituals. Like whiskey time and sharing Pavone stories in the green room with the crew. In a ridiculous backstage speech from Glass where the band gets on all fours, barking like dogs, before chanting “nothing will stop this band” and a countdown to “KYLE!” then hitting play on the laptop to start the show.

For this tour, his voice is in the live mix for tracks off 2013’s Tracing Back Roots too. Listen closely and you’ll hear him singing onstage.

The wiry brunette with a goofy, infectious smile was larger than life and, the way his friends and bandmates tell it, you wanted to be a part of whatever he was doing. Pavone had a reputation for living in the moment, of giving himself over completely to what was happening right in front of him and bringing those closest along for the ride. That included the fans.

“[WCAR] talks about love,” high school friend Stevie Garofolo says, “but Kyle made the audience really feel it.”

It lives on in the growth he’s forced the band to face, musically and personally. “If everything was super easy, and perfect and laid out,” Glass says, “there would be no story, no mountain to climb.”

“The fact that we all came together and decided this was still our dream and still what we’re going to dedicate our lives to,” Moore says, “it says a lot about the character of a person and the perseverance to still be here after all the shit that’s happened.”

For example, Stephens starts vocal prep a month before everyone gets together. He’s changed his diet, and how he behaves on the road. Now he only cuts loose after their home closer. It’s when “Hallway Dave,’’ relieved of singing duties, makes an appearance and starts drinking only to pass out in a liminal space at someone’s house soon thereafter.

“The biggest thing that’s changed is me taking my role as a singer really seriously,” he says.

Of course, the band would trade anything to have Kyle back. He was the life of the party, chaotic energy. Some of that still exists, but not to the extent it once did.

“There’s a little more stoicism involved now,” Puckett says.

But for all the darkness of Pavone’s passing, it gave the band a new mission. A reason to keep playing.

“We know the impact we want to leave behind because we don’t want anyone to go through what we went through,” Puckett says. “It helps us sleep better at night.”

In the years that followed Pavone’s death, WCAR took an audit. After spending their adult lives making music and playing live, did they want to continue? Following COVID lockdowns and spending more time with their families, the guys realized how much they missed out on after a dozen years on the road. They also realized how much they missed touring.

Rather than force themselves to eat shit on the road 10 months a year to make ends meet, they would spend six months touring and six months off. The guys make enough off the music and live show to give them an average American salary. Puckett said it’s not a ridiculous amount of money, but it being a really cool job makes up for it. Each band member has their own side hustle to supplement their music income.

Every night of the Darkbloom tour has sold out, including a band-record 2,000 seats in Orlando. Apprehensions about playing in certain markets on such a lean bill had vanished when I talk with Moore and Glass halfway through the tour. Glass looks tired, and mentions their hour-ish set leaves him exhausted afterward. He’s excited to come back for a sold-out show where it all began, though.

“Detroit shows go a little harder,” he says. “They know you’re there to give it your all because it’s the origin of where something really special was created.”

It does add a little extra pressure, however.

“It’s like a video game where you fight the final boss,” Glass says. “You don’t want to fuck up your hometown show.”

Moore says last October’s intimate shows at The Loving Touch were a proving ground for the new music. Seeing the way the audience of friends and family reacted to those heartfelt tracks gave Moore confidence they’d be received well everywhere else.

That support network is what makes playing Detroit different from any other city on the planet, being surrounded by those who’ve cheered you on since day one and know the road you’ve traveled. When Moore started crying halfway through introducing somber album closer “Promise You” last October, his wife parted the crowd to hold his hand onstage and he was able to get through the speech and play the song. Watching his dad sing every lyric doesn’t get old either.

“Just being surrounded with the people that have been there since we were practicing really shitty metalcore in their basements,” Moore says, “there’s something special about that for me.”

Coming soon: Metro Times Daily newsletter. We’ll send you a handful of interesting Detroit stories every morning. Subscribe now to not miss a thing.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter