Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Marcus Belgrave's Homecoming Band plays 8:30-9:45 p.m. Sunday, Sept. 3, on the JP Morgan Chase Main Stage on Hart Plaza.

Trumpeter Marcus Belgrave is no stranger to big projects.

He's organized or played a key role in all manner of collectives, DIY recordings, workshops, concert series and such. Last year, he staged the massive Heidelberg Suite, a big-band-plus-strings homage to Detroit artist Tyree Guyton, co-composed with guitarist Anthony Wilson.

Come Labor Day weekend, Belgrave will be at it again. At the urging of the Detroit Jazz Festival's artistic director, Chris Collins, Belgrave has put together an all-Detroit, all-star jazz ensemble, which includes Detroiters Marion Hayden on bass and Vincent Bowens on sax. That's along with former Detroit trombonist Curtis Fuller and drummer Louis Hayes, who became part of the New York scene back in the '60s, and vocalist Harvey Thompson, who's spent his recent years in Japan. Up-and-coming Ian Finkelstein joins them on piano.

It'll all be billed as the Marcus Belgrave Homecoming Band, specially tooled to play the music of the iconic composer Horace Silver, jazz classics like "Song for My Father," "Señor Blues" and "Sister Sadie."

"I can't think of a period in my career since doing those grueling one-nighters when I was touring with Ray Charles that I have not been busy," Belgrave said on a recent Sunday afternoon, sitting on the patio of his Ann Arbor home, reminiscing about his storied career, and the hectic present. The present, to his dismay, is complicated by a serious bronchial condition that has vexed him for the last three years.

A tank of oxygen and medication regimen are constant companions, slowing down his performing and teaching schedule just when he'd like to be more active than ever. In mid-August he was hospitalized to have fluid removed from his lungs when he slacked off on the meds that he felt were hindering his playing.

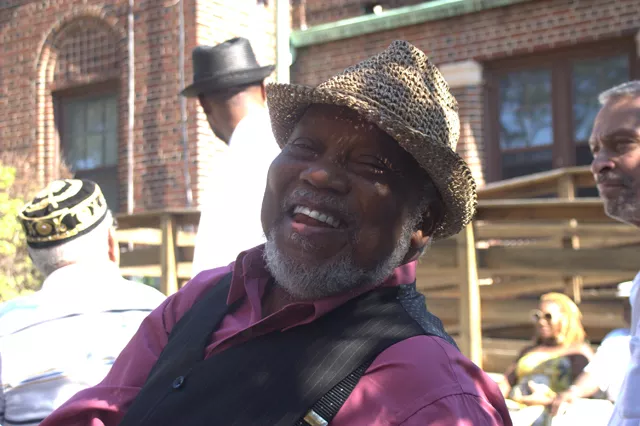

But this day, he's in good spirits, even if his breathing is a little labored. And to be around Belgrave in a talkative mood is to hear his career and experiences come alive. He's been playing since his teen years and, six decades on, at 76, he has the key to a vast warehouse of stories. Ray Charles, Charles Mingus, Booker Little, Wynton Marsalis ... he's walked with the legends.

There is the one doozy of a tale about leaving Ray Charles — or rather trying to. With a complaint to the union that the young musician had walked off with one of the band uniforms, Charles essentially shanghaied Belgrave back into service.

That cut short his work with Charles Mingus alongside alto saxophonist Eric Dolphy. Mingus, by the way, Belgrave explained, had a special way of magnifying what he paid his musicians. He paid them all in singles.

"We'd be walking around with a wad of money in our pockets, thinking we were doing something," Belgrave recalled.

Belgrave grew up in Chester, Pa., and he started playing the trumpet at age 4. He studied with his dad for eight years. Then he took private lessons. At 15, he met and sat in with his boyhood idol, bebop trumpeter — heck, co-inventor — Dizzy Gillespie.

"They used to have dances around the city and jazz musicians used to play them. My friends took me to one that Dizzy happened to be playing. I was 15, and I had just learned how to play all Dizzy's solos. I asked could I sit in, and Dizzy asked my friends if I could play. I played one tune and Dizzy left the bandstand and went outside and started hitting on all the girls. He liked my playing so much that he let me play out the rest of the set, but of course he didn't pay me."

In 1958, Belgrave was a shoo-in for a spot in Dizzy's big band, but the spot went to Lee Morgan, and Belgrave went to the Army. After he was honorably discharged, he joined Ray Charles' band and toured two years. Then he moved to New York, when the city was studded with trumpet players of the caliber of the aforementioned Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, Donald Byrd, Johnny Coles and Booker Little.

Those cats had the choice gigs cutting records. Belgrave worked here and there, but he couldn't get a record deal. He went back on the road with Ray Charles from 1959 to 1961. Finally, he moved to Detroit and got steady session work, thanks to Motown hit songwriter Norman Whitfield.

That's also when the great lost Belgrave records were cut, three albums' worth of jazz recorded at the Graystone Ballroom with George Bohannan, Kirk Lightsey, Pepper Adams, Paul Riser and Cecil McBee. The tapes are still in Motown's vaults somewhere, despite his attempts to buy them back.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Belgrave became a mentor to a bunch of aspiring jazz musicians: Kenny Garrett, Regina Carter, Geri Allen, Marion Hayden, and Robert Hurst. Given Belgrave's long list of accomplishments, he acknowledges he's most proud of shaping those musicians.

He taught at various venues, from impromptu sessions at nightclubs to schools and community centers and even in home workshops similar to the legendary ones the pianist Barry Harris held at his home during the 1950s.

Belgrave's workshop was open to any young musician who was serious about playing jazz.

"I got a strong foundation from Marcus. It didn't matter that I played the violin. I could have come to him if I played the kazoo, and he would have taken me in because I was genuinely interested in the music," said violinist Regina Carter recently during a telephone interview from her New Jersey home.

Carter continued: "Marcus is a gem and he's full of stories and history. You can get a degree in music just hanging out with him."

Bassist Hurst was a 10th grader at Rochester High School when he met Belgrave at a school concert. He asked his band director if he could play a duet with Belgrave. Belgrave liked Hurst's playing and hired Hurst for some gigs.

Hurst said, other than his dad, Belgrave was his most influential mentor. Belgrave could play his butt off, conducted himself well and always lived a good life. He prepared Hurst for life as a jazz musician, instilling in him the importance of continuing the art form through teaching.

They'll take the stage to give props to a musician who's built an international reputation over the decades. And despite the health issues, he doesn't plan to slow down. He keeps looking for the next big project. It could be a record with Blue Note Records, which would be his first disc as a leader for a major label. (Although, for the record, he's been prominently featured on major label releases before. Notably, he was a star on Geri Allen's 1991 Blue Note release The Nurturer, which was pretty much a tribute to Belgrave, beginning with the title.)

Before his wife and manager, vocalist Joan Belgrave, cut the interview so Belgrave could take his scheduled breathing treatment, he was asked how he feels about being partly responsible for the successes of Hurst, Allen, Carter and Hayden.

Belgrave answered in his low, raspy voice: "It makes me want to keep on giving and keep on living."

Charles L. Latimer will post to the Metro Times Music Blahg during the festival. Send comments to letters@metrotimes.com