The last word on the MC5

Against all odds, a new oral history about the influential Detroit rock band is finally here

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

The first time music journalist Ben Edmonds heard about the MC5, it was from musician friends in a band called Magic Terry and the Universe. He liked what his friends had to say about the band, so Edmonds made sure to go to the MC5’s first New York City show at the Fillmore East. The verdict? “I thought they were hands down the best rock and roll band I had ever seen in my life. It’s an opinion I hold to this day,” Edmonds told journalist Jason Gross in a 1998 interview, adding, “With all the research I’ve done and all the time I’ve spent thinking about the band, I’m not sure I can put their legacy into a simple sound byte. The story is far more complex than anybody knows… What exactly is the legacy of this band that I’ve spent most of my life obsessing over? We’ll see.”

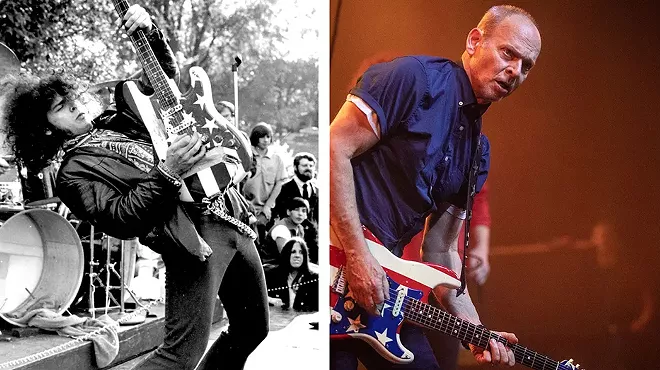

An answer to that question is presented in MC5: An Oral History of Rock’s Most Revolutionary Band, out now from Hachette Books. The book is based largely on Edmonds’s extensive archive of material about the band formed in Lincoln Park in 1963, and was shaped into existence by CREEM editorial director Jaan Uhelszki and author and former Guitar World editor Brad Tolinski, who share a byline with Edmonds. Its release comes near the end of a year in which the last remaining founding members of the MC5 and its manager have died, and right at the cusp of the band’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the “Musical Excellence” category later this month in Cleveland.

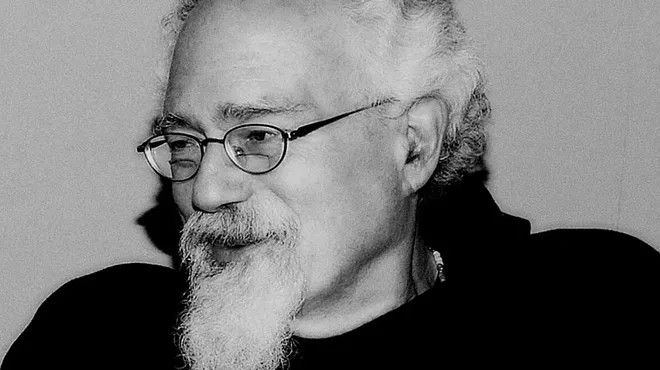

MC5 diehards had heard rumors of Edmonds’s book for years, plans he had given up on until he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2015; Edmonds died in 2016 at age 65. In an obituary in the Detroit Free Press, Ben Blackwell of Third Man Records shared that Edmonds had told him, “‘I can’t do that book and keep everyone happy. If I put out the book the way I want it, everybody’s going to be pissed off.’ … So his stand was, ‘I’m not going to do it at all.’”

But Edmonds’s unexpected cancer diagnosis changed all of that. He asked Uhelszki, his best friend (and later, literary executor) to come to Michigan to help him finish the book. She tells Metro Times, “I said, ‘Sure, I’ll do that.’ I’m thinking it’s three-quarters finished, in a month I could, you know, help him just jam it out, and we’d finish it. And when I got there, there wasn’t anything. There were, like, boxes and boxes and boxes of handwritten transcripts. He didn’t type anything. So I sat in a back bedroom for three weeks and read everything that was in there.” Eventually she had to return to her life and work in California, but with the intention that they would continue to work on the book together. “Of course, he thought he could beat it,” she says, “and I wanted to believe it.”

After her friend left the planet, Uhelszki decided that the way she could keep her promise was to put together an oral history, based on those thousands of pages of interviews. She enlisted the help of Tolinski, a fellow Detroit-area native. She’d previously worked with Tolinski during his 20-year tenure as editor of Guitar World, putting together a 30,000-word package on Alice Cooper’s Billion Dollar Babies. She also knew he’d worked through massive quantities of interviews for his previous books on Eddie Van Halen and Jimmy Page. Eight years later, the results of that collaboration are here, ready for fans, friends, and the MC5-curious to enjoy.

It’s important to clarify that putting together an oral history is still, very much, writing a book. It’s more involved than simply pulling out chunks of interviews and lining them up logically in some kind of order. To do it right requires a deep knowledge of the subject matter as well as the ability to identify what is important, what is bullshit, what contradicts something someone else says later, what is the opposite of something the same person said in an earlier interview. In this context, contradictions aren’t always “gotcha” moments; they can be human error or they can be major opportunities. You also have to create a chronology, a timeline, and a narrative arc — what is the story you are telling, and how are you telling it? What’s over-represented, and what’s missing?

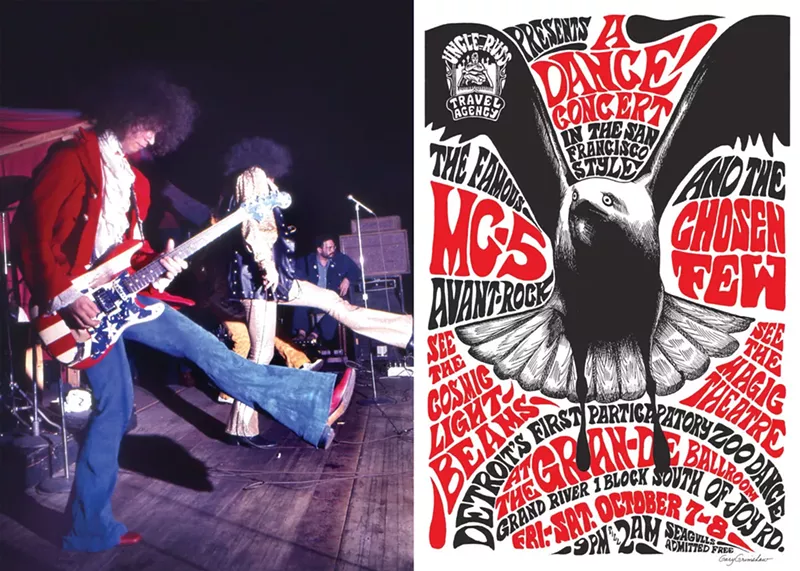

And that is the place where this book excels. Uhelszki was there, not just at CREEM, but as a teenager in Detroit in the late ’60s, taking in as much live music as she could. Uhelszki explains that she first saw the MC5 in the early fall of 1966, playing at the Michigan State Fairgrounds, before seeing them at the Grande Ballroom, the storied Detroit club where the MC5 would become the house band and later record their first album, Kick Out the Jams, in 1968.

This isn’t in the book, but it should be: Uhelski and her friends were only 15 at the time, too young to get into the Grande legally; you had to be 17. So she borrowed a friend’s sister’s ID to get through the doors, and once inside: “We’d go up the girls bathroom and we would drop the ID down to our other girlfriends through the bathroom window, and that’s how we all 15 year olds were getting into the Grande Ballroom.” That borrowed ID turned out to be kismet, as the sister of the ID owner was dating someone who worked at the Grande, and she told him that he should hire her friends.

Before you ask how underaged kids were working as bartenders, the Grande didn’t serve alcohol; they didn’t even have a liquor license. (Russ Gibb, the late Grande founder and impresario, once said: “We really didn’t need drinks in those days. There were plenty of other ways to get high.”) But this was how a 15-year-old Jaan Uhelszki suddenly found herself behind the bar at the Grande Ballroom, serving up trays of Pepsi and Sprite and orange pop (at 15 cents a glass) to thirsty concert-goers between sets. “I always took the station at the very end of the bar, near the girls’ bathroom, so I could see the band,” she remembers. “My job was really to dole out the drinks and to make sure people didn’t put LSD in them.”

It’s hard to get much closer to the story than that, or have better bona fides to weigh in on its accuracy. Combining her real-life experience with her years at CREEM in the early days of rock journalism uniquely positions Uhelszki as the one Edmonds entrusted with the burden of materializing his magnum opus. None of this is in the book because it’s not her story, but it still informs and supports the work as much as her skill and experience as a music journalist.

MC5: An Oral History of Rock’s Most Revolutionary Band is a book written by two people who never planned on writing it, drawn from the archive of the person who considered it his life’s work, but made a decision to not pursue it. That’s an enormous responsibility and a whole lot of juju to take on. It’s also one thing to finish a book someone had already started. It’s another to have to manifest it into thin air from thousands of pages of raw handwritten interviews and have it meet your personal journalistic standards, have it do justice to the band’s work and legacy, and to get it right. The verdict? They do.

The chronology is clean and logical; there’s no advanced literary techniques or anything fancy. There are no large jumps between eras taking the reader out of the place they are in and forcing them to make connections they may not be able to. The book clocks in around 267 pages, and feels even and balanced despite there being more material from guitarist Wayne Kramer (because he was a notorious motormouth) and vocalist Rob Tyner (because Edmonds spent an enormous amount of time with him and his wife Becky). Nor does anyone get off easy. The book moves forward, always onward, and there is energy and personality — there’s a memorable quote from someone on pretty much every page.

You couldn’t tell this story without Big Chief John Sinclair, and he offers his perspectives not just as the manager of the MC5, but also as a major cultural arbiter of the place and the time. They also make sure that there’s enough space for other key voices, like Gibb, poster artist Gary Grimshaw, or the late Ron Asheton of the Stooges. And Becky and Chris Hovnanian (Wayne Kramer’s girlfriend at the time) are there because they were willing to speak on the record and because they were witnesses to events — “They were like Beatles’ wives,” Uhelszki says — but also, they’re part of the story because they made the band’s outrageous, flamboyant stage gear. “Our pants were a universe unto itself,” Tyner says in the book. “They were made to be worn sans underwear and designed to be as provocative as possible.” Hovanian tells the story of spotting a tapestry rug at a fabric store and deciding it would make a nice jacket for Wayne Kramer, or a combo of orange satin pants with matching orange ruffled shirt.

The authors are absolutely not reticent in using material that may not show the individuals in question in the most positive light, whether it’s the band ganging up on Tyner (because they didn’t think he was cool enough) or any number of drug-related sagas. There’s honestly nothing that terrible or earth-shattering, which makes one wonder what Edmonds was specifically concerned about, but the passage of time also tends to wear down the sharpest of memories. It also makes sense that a band that was so important to so many people would have the staunchest defenders of its honor, especially one that many right-thinking folks would agree never got the respect that it was due.

This is a chewy book. It is substantial. Uhelszki and Tolinski pack a lot of substance into every page. The chronology they establish does the work of guiding the reader through the story, but at no point does it feel like a slog, despite its complexity. There are a lot of voices, a lot of perspectives, a lot of history, a lot of moving parts, and what you feel is not the weight of the quantity of the material, but the weight of the story. You will be a little lost if you are coming to this story without knowledge of the basic history of Detroit or an understanding of the major cultural touchstones of the ’60s, but it’s not as though the authors don’t provide context. If anything, you will come away from this book understanding exactly to what extent Detroit is a company town, which is hard to see if you didn’t grow up here.

Guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith, who died in 1994, is the one voice who is not in the book directly. There are no interviews with Smith in Edmonds’s archive; Uhelszki confirmed that there are no notes indicating whether Edmonds tried to talk to him and he declined, if there was a larger issue than that, or if, as the book points out repeatedly, he was simply not a man of many words. But despite that formidable hurdle, Smith is still very present in this book. The narrative does an excellent job of incorporating observations and insights from the other members of the band and its inner circle about Smith, but what would have been helpful to readers coming to the book was if they’d provided some kind of warning or clarification somewhere about why his voice wasn’t included.

If you love the MC5 and this is your band, this is the book you have been waiting for. It’s going to be hard for any book to meet that level of expectation but it feels fair and accurate in that no one in the book gets off lightly. There are no publicists hanging around at the edges sanitizing any of this book. Uhelszki notes, “I had to go through a really extensive permissions procedure because the publisher was afraid that they would resent things that they said.” But everyone in the band, or their surviving representatives (like Davis’s wife) signed off on everything that the co-authors had included in the book.

Does this book make you care about the band if you don’t already? If you’re interested enough in the history of the MC5 and want to try to understand why they’re important, this book does the best job of anything that’s come out thus far in terms of telling the story of the band from start to finish. It brings you into the band’s days playing teen clubs and sock hops, into the Grande Ballroom and to the chaotic 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention (where the band performed as part of the protests against the Vietnam War), through the missteps and questionable decisions (and the truly bad ones), through the internecine battles and the drugs and the decline and the complete and total free-fall that ended the band. It is all here, and you get to hear about it from the people who lived through it in their own words. While we’ll never have the benefit of Edmonds’s incisive observations and keen analysis (and enthusiasm!) about the band — not to mention his great writing — it is what Uhelszki could do and still keep her promise. And what the reader still benefits from is what she refers to as Edmonds’s “lethal interviewing prowess. There is no question the man wouldn’t ask.”

If you’re already converted, at points this book will make you want to reach into the pages and grab each person and tell them that they are making a huge mistake, to please not do that, whether it’s casually try heroin or move into a house together in the middle of nowhere to make their next record, or ask their parents to front them the down payment for a Jaguar they can’t actually afford just to maintain appearances. Even if you think you know all of the stories, it is another thing to read them adjacent to each other. Even if you know what happens next you will feel uncomfortable. This isn’t a story with a happy ending, but it’s a story that Edmonds wanted to tell, that needed to be told. Now it has.

There are a number of upcoming events around the book’s release. There will be a discussion with the co-authors featuring a performance by the Detroit Cobras from 7-8:30 p.m. on Friday, Oct. 11, at Rivera Court at the DIA; 5200 Woodward Ave., Detroit; dia.org; the event is free to attend with museum admission. There will also be a celebration of the MC5 sponsored by the Lincoln Park Historical Society from 3-9 p.m. on Saturday, Oct. 12 at the Memorial Park Bandshell in Lincoln Park; lphistorical.org; the event is free to attend. There will also be a book-signing from 3-5 p.m. on Sunday, Oct. 13 at Book Beat; 26010 Greenfield Rd., Oak Park; thebookbeat.com.