Quincy Jones suggested in his autobiography that the difference between 1950s-era jazz and hip-hop artists is this: Most jazz artists were more concerned with mastering their craft.

Hip hop is driven as much by profit as aesthetic.

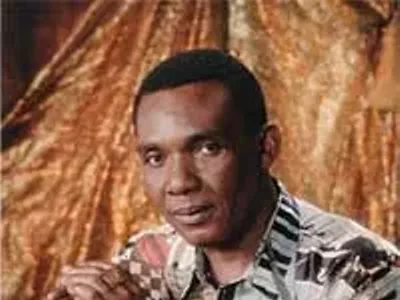

Take 25-year-old Detroit emcee Owen "Swann" Raines. The year 2005 was one hell of a ride for him. He won two nationally televised rap battles, one of which was aired as a reality show episode. Then, at the Vibe Awards, he was hailed Best Freestyle Rapper in a ceremony shown on VH1.

It's an interesting career path that's landed Swann on MTV twice, and made his name and likeness Internet-ubiquitous. MTV documented Swann's triumphant treks to the Fight Klub and the Rap Olympics — two hugely popular national competitions — last year for its reality show, True Life. Viewers may recall the emcee sprinting through the street with his pants down, waving the enlarged $5,000 check he'd just scored after winning the Fight Klub. The network also aired the Roc-a-Fella Records battle, where the unknown rapper nabbed second place.

Battles have earned Swann international acclaim, while providing him with the means to pay his bills. "I've made tens of thousands from it," he says. "I'm real proud of that."

As things go with fame, he's had parts of his personal life aired that he might've kept private. An appearance on the MTV reality show True Life led to the outing of a particular addiction — sex — which the network waved to the world like a hip-hop freak flag.

And all of this from rhyming.

So what makes rap battling so popular? It seems simple enough, if you can stand in a circle surrounded by an incendiary crowd, and then string together a bunch of rhymes more clever and insulting than those of the opposing emcee, who's probably pointing and gesturing in your face. In fact, he or she might get close enough for you to smell the rosemary on last night's chicken dinner.

Through it all, your rhymes are supposed to be delivered spontaneously and in time with the beat. That's called freestyling. Simple, right? Hardly.

At a glance, Swann is an opponent's wet dream. He looks like a wild-haired black computer geek with an awkward tilt, and on TV he wore circular glasses, and a dingy sweatshirt over a slight pot of a belly.

The garb's a ploy, of course. It's like Eminem waiting for opposing emcees to reference him as the only white guy in the room. Swann knows that, when battling, someone will rip on his purposely unkempt appearance without understanding the get-up is so obvious that there is no joke. It's too easy.

His style, meanwhile, is surprisingly simple. "I don't use no multisyllabic metaphors," he says. "I just be straight joke-crackin'. 'Ya nose is way too big for your face,' shit like that. I found it was just that simple, and it got the crowd response."

Swann built a rep as a battler at Mumford High School in the early 1990s. A few years later, he entered the Detroit hip-hop scene with his crew, the Mountainclimbers. Stryke, the emcee who played Lickety Split in 8 Mile, was a member. The group opened shows for Capadonna, De La Soul and Usher, and much like the legendary Wu-Tang Clan, the Mountainclimbers had strong personas.

Swann says his role in the group was to be the competitive edge. It wasn't long before his rep began to precede him. "Cats knew if I was gonna be at an event, it was gonna be a problem," he says. "I was going up against people I learned the game from. Cats like [Slum Village's] Elzhi. He's one of the illest to ever consider rappin'."

He also counts Proof, Eminem and Jin as some of the best battle emcees in the country.

The respect is mutual. "The guy's skill level is crazy," Elzhi says. "I've seen him flawlessly murder cats in a battle. A couple times, he's told me, 'Yeah, this gon' be easy. I'm gon' do this, and blah-blah-blah.' And he did it."

Turning passion into profit wasn't as easy, however, because props didn't follow every battle. At 20, Swann entered The Source magazine's Unsigned Hype battle. He got disqualified or, as he says, shafted. Disappointed, he quit and went into the corporate world. He used the gift of gab that worked so well in battles to win a position as a manager in the Environmental Services Department at Botsford General Hospital, a boast confirmed by the hospital.

"I was the man," he says. "I was like a kid with a new toy. I had 100 employees, and I was straight-laced, by the book, suit, tie."

He says he relished the power that came with the position. Subordinates had to call him "Mr. Raines." He says he found terminations therapeutic, especially on bad days. He'd fire people to make himself feel better. Just make a note of any insubordination, and wait for an opening. Kinda like battling.

"I used to tell my employees I wasn't just their boss. I was the illest rapper in Detroit. They still call me from time to time, 'cause they can't believe they saw me with my pants down, running around with a $5,000 check."

But hip hop kept calling. The Motor City scene was progressing, and new names were being bandied about. Q.W.E.S.T. McCody and Marv Won became marquee monikers on the battle circuit. Swann turned in his two-week notice.

He traveled, suffered canceled competitions and settled for auxiliary status in others until the MTV battle opportunity came up.

Swann laughs at the mishaps, saying, "They say if you throw enough shit at the wall, some of it is bound to stick." The rest is underground history.

If there is one byproduct of his modest fame that he finds regrettable, it's MTV's disclosure of his battle with sex addiction. But Swann admitted it on television, and even allowed MTV cameras to attend a Sexaholics Anonymous meeting with him.

"True Life exposed it a little more than they needed to, but I can't really dispute it," he says. "These chicks, man. That's my vice. If you've never been to one of those meetings, it sounds funny, but it's not funny at all. It's hard to imagine pussy being that serious. But it's dudes whose lives are in serious jeopardy 'cause they can't keep their dick in their pants. One dude's son almost drowned, 'cause [the son] was in the pool, and [the father] didn't notice 'cause he was beatin' off to some girl in a bikini."

Swann says he learned that any enjoyable activity becomes a problem when it hinders productivity. He uses rap to exorcise his own demons, albeit with comedic flair. Take "Crack Addict," a song he recorded for his forthcoming independent release Uncommon VIP. It ain't about smoking rocks.

The album drops this spring. Swann has the luxury, given his underground, Internet-savvy following, of taking his time to deal with major record companies. So he might win yet again.

"It's a wonderful thing, what Swann's doing," Elzhi says. "He's defeating the odds. A lot of people faded away from the scene. They felt they had to go in the studio to get noticed. But Swann is overcoming all the obstacles. He's done the impossible."

Khary Kimani Turner is a freelance writer. Send comments to [email protected]