Remembering the funky, out-of-this-world life of Detroit’s Amp Fiddler

The late performer was a mentor to many in Detroit’s music scene

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Back in the day, orbiting above the Detroit skies, the Motown Satellite showered the city in soul music. Everyone in the Motor City bopped to the beat of Young America. But eventually, the Motown Satellite sailed off to another solar system, leaving hundreds of wannabe soul children in its wake. After years of dutifully imitating the doo-wop and dance routines of their harmonious idols inside the garages and basements of their parents’ homes, hoping that someday they would join the satellite’s roster of singing sensations, the soul children now found themselves without a launch pad. So, they built their own. For them, building a career was a labor of love. And to one soul child, it was more than love — it was a religion.

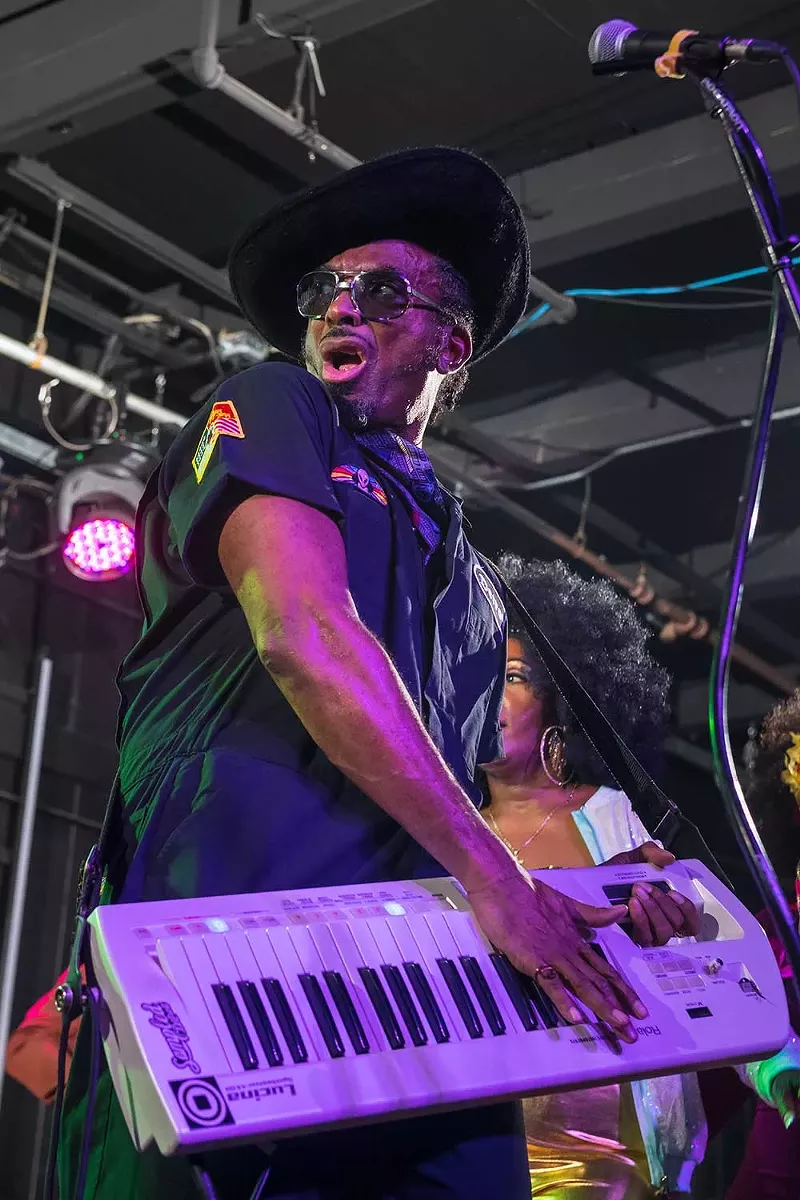

He went by many titles: pianist, composer, arranger, singer, songwriter, rapper, teacher, mentor, techno-brat, and futurist. First and foremost, he was an artist in every sense of the word. What constitutes an artist is originality, and Joseph Anthony Fiddler was truly an original. Music was his passion, a fusion of funk, jazz, techno, reggae, Afro pop, soul, rock, rap, and gospel. An arch-futurist who avoided the weepy ballads and the feel-good anthems of R&B, he created new music, new sounds. But his greatest creation was himself — Amp Fiddler.

His wonderfully funky career came to an end on Dec. 18 at age 65. This year, he was the recipient posthumously of both the Grammy for Best Alternative Jazz Album for his contributions to Meshell Ndegeocello’s The Omnichord Real Book. He was also recognized in the “in remembrance” tribute video at the NAACP Image Awards.

Young Amp — a childhood nickname — grew up on Fleming Street in Conant Gardens, a neighborhood of Detroit. Born into a musical clan, Amp heard his dad, Cleophas Fiddler, a lineman for Uniroyal, sing the songs from his youth growing up on the Caribbean Isle of St. Thomas, Amp’s first sampling of reggae. He listened to classical records on the family phonograph, purchased by his mom Christine from the J.L. Hudson department store, where she worked. His older brothers Charles and Thomas (Bubz) had not yet begun their musical ascent as saxophonist and bassist. At the age of 9, Amp had already mastered a couple of Motown compositions on the family baby grand piano. Christine was Amp’s source of strength and she, in her wisdom, succeeded in implanting a strong belief in himself and offered to pay for her son’s piano lessons.

“Motown was alive and kickin.’ Motown music was everywhere,” recalls neighbor and fellow musician Bill Parker. “All we listened to was soul music. After Motown left, Black music continued to grow bigger than ever. We were the only two Black families in Conant Gardens that were Catholic. I think that’s why me and Amp clicked, because we had the same religion.”

In addition to Amp’s brothers, he also had two older sisters. Deborah and Mystic were also musically inclined, and it was Mystic who opened her little brother’s ears to musical possibilities around him.

“When I knew her back then, she wasn’t Mystic. I knew her as Sandra,” Parker says. “Sandra was an adventuress; a civil rights and peace activist, Fleming Street’s very own full-blown Black love child. She wore the regalia of the hippie culture — love beads, fringe vest, mini skirt, and go-go boots. She read tarot cards, dipped candles, studied Eastern philosophy, and could quote both Gandhi and Chairman Mao. Sandra’s greatest achievement was bringing rock ’n’ roll music into the neighborhood. [She] owned an extensive and eclectic record collection which she shared with me and Amp — Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, the Beatles, Taj Mahal, you name it. After a steady diet of soul music, hearing rock for the first time blew our young minds.”

Then there was Mr. Chick, who lived next door to the Fiddlers. On warm summer evenings sitting in a weathered chaise on his front porch, Mr. Chick would strum on his Gibson guitar. A sideman once for the blues legend John Lee Hooker, he accompanied the singer on stage at the Apex bar on Hasting Street. On those summer nights, Amp and Bill sat on the porch railing, soaking up the music. Mr. Chick entertained his young visitors with renditions of Robert Johnson’s “Me and the Devil Blues,” Muddy Waters’s “Delta Blues,” and Hooker’s own “Boogie Chillen,” to name a few.

Just as Mystic had opened their minds to the future, Mr. Chick opened their minds to the past. A nascent guitarist himself, Parker pestered Mr. Chick on finger placement, whereas Amp questioned the sideman on musicianship and received one of the best pieces of advice given to the young pianist. “Check your ego at the door,” Mr. Chick told him. Later, Amp turned Mr. Chick’s words into a mantra.

“We started a band in middle school with Amp on piano, his brother Bubz on bass, me on guitar, and Mikey down the street on drums,” Parker says. “We practiced in the Fiddlers’ living room ‘cause the baby grand weighed a ton and brother, nobody was lugging that thing around.”

It takes money to run a band, however — to buy equipment like effect pedals, guitar and piano strings. “Every time we needed a piece of equipment like a bass pedal or something, Amp and me would pull a Butch and Sundance,” Parker says. “Downtown, Grinnell’s music store sold everything, from pianos to sheet music and every musical instrument between. Downstairs, I was swiping effect pedals and upstairs Amp was five-fingering chromatics. Hendrix used effect pedals. Hendrix is my hero, to me, Hendrix was Black Elvis. To achieve the sound Hendrix achieved, I had to use the pedals Hendrix used. See, I never stole nothing I didn’t need. Makes sense, doesn’t it? What didn’t make sense was the harmonicas Amp swiped. No one remembers hearing or seeing Amp ever play harp. Never played one in concert or on any of his CDs. Anyway, our little light-finger larceny ended abruptly when we got busted swiping records at Federal’s Department Store.” (Another source says that Amp could often be seen with a harmonica, and would sometimes keep it in his shirt pocket, bedroom shelf, or studio desk.)

Tall and lanky like his Dad, the teenage Amp, a rocker in elephant-leg bell bottoms and five-inch platform shoes (making the teen even taller), was like most boys his age awkward, especially toward the opposite sex. The girls who were attracted to Amp had to hit on him first, mistaking his shyness for stoicism.

Amp loved the music more than he loved the ladies. That love deepened each time he attended a rock concert.

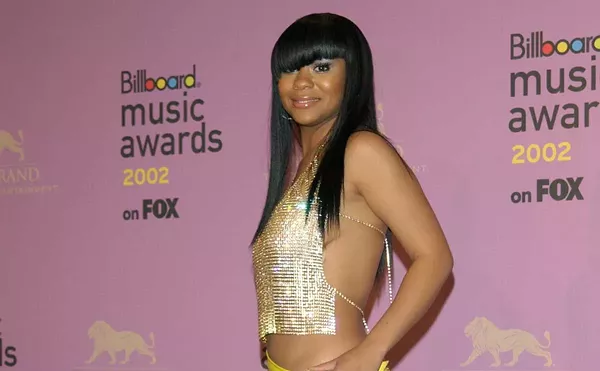

“Most shows we would sneak in,” Parker says. From Aerosmith to Frank Zappa, Amp saw the hottest rock bands of the period. His favorite was Sly and the Family Stone. Amp enjoyed the band’s tight-knit musicianship, the funky quality of their arrangements, and the topicality of lyrics on tracks like “Don’t Call me Nigger Whitey,” “Everyday People,” and “Life.” The teenaged Amp marveled at Sly Stone’s stage presence, envying his sartorial splendor of gold lamé jumpsuits and the Afro mushrooming beneath a large-brim rhinestoned Stetson.

A new breed of hero appeared on the musical horizon — keyboardists like Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Jan Hammer, and Rick Wakeman of the progressive rock band Yes. The sight of Wakeman on stage surrounded by Moog synthesizers greatly impressed Amp; the electronic sounds of the synthesizers changed the young musician’s life forever.

After the shows, whether it was a school night or not, Amp would return home and practice on the Fender Rhodes electric keyboard Christine bought him into the wee hours, sometimes till sunup. But no matter how late Amp practiced, he never missed a day of school. He attended Osborn High School where he excelled in music, as well as athletics (he played point guard on the Osborn Knights varsity basketball team) and art (Amp aped the drawings of R. Crumb and Gilbert Shelton). His drawing abilities came in handy later when sketching his stage wardrobe. Unlike his contemporaries, he enjoyed every bit of school ever since he was an altar boy at Holy Ghost. Amp relished education, but his father died before Amp graduated high school.

After Osborn, Amp did stints at both Wayne and Oakland Community College. Then, onto Oakland University, where he majored in composition and music theory.

It isn’t clear whether Amp met pianist Harold McKinney on Oakland’s campus, where Mr. Kinney taught music, or in the neighborhood where they both lived. But the important thing is that they met. McKinney was founder of the Detroit Jazz Heritage performance lab workshop held in Detroit’s SereNgeti Ballroom, where he tutored countless young musical hopefuls.

With Amp, it was different. McKinney, who had observed Amp’s piano playing on campus, took the student under his wing for personal lessons instead of lumping Amp in with the rest of the pupils at SereNgeti. Both teacher and student immediately clicked, sharing a love of classical music and trumpeter Miles Davis. Apart from Amp’s musicianship, which McKinney thought exceptional, he also found the student’s self-assuredness, as well as the unwavering self-determination instilled by Christine, to be exemplary. Under McKinney’s tutelage, Amp found a kind and knowledgeable mentor, a title Amp would one day wear in the future.

By the mid-’70s, disco music had practically killed the doo-wop quartets. Everyone in the music industry, from the Rolling Stones, Elton John, and even Marvin Gaye, betrayed their roots and jumped aboard the S.S. Disco. Which isn’t to say that there weren’t any doo-wop groups around — there were, like the Enchantment and the Floaters. Both were of Detroit, and both had No. 1 singles on Billboard’s top ten. Amp landed his first gig with the Enchantments thanks to his childhood friend Garry Green, brother of Bobby Green, who was an original member of the group. “Bobby told me they needed a new keyboardist because the old one had left,” Garry says. “So naturally, I told my boy Amp to audition. I knew he could do it and Amp knew he could.” Bobby continues, “I did know Amp. I knew Amp as my younger brother’s running buddy. That’s all I knew about him. I didn’t know he could play keyboards.” On the day of the audition, Emmanuel, the lead vocalist and the de facto leader of Enchantment, hired Amp on the spot.

Amp left college soon after he was hired and toured a year with the group before he jettisoned to R.J.’s Latest Arrival, this time a homegrown rhythm and blues band, but Amp spent less time with R.J. than he did with Enchantment. Amp might have checked his ego at the door, but in private, it rankled him playing soul music when he wanted to play rock ’n’ roll. In a 2003 Red Bull interview Amp spoke of those early years, saying, “I’d been involved in doo-wop and I didn’t like that… because before that, I was listening to Janis Joplin and Hendrix, the Beatles, rock ’n’ roll, Motown.”

Soon, he found himself on a plane heading to Europe with the band Was (Not Was) as a sideman. It would be Amp’s first visit to Europe, but not his last. All the dough he made touring he spent on electric keyboards and drum machines, making a plethora of mixtapes and new sounds and passing out demos to anyone and everyone who could help him professionally. George Clinton, mastermind behind the funk bands Parliament and Funkadelic, was never far off in Amp’s thoughts. Many of the demos Amp made, he made with Clinton in mind, partly because he was a fan of Clinton’s music and the fact that the funkmeister was accessible, living in Detroit in the post-Motown years.

“Parliament-Funkadelic stuck in the back of my mind,” Amp said in the same interview. “I had just started to play a little keyboards. I think we have to keep our vision as far as who and where we want to be in our future … We have to say it to become it. And beyond that, you’ve got to say: ‘I am that and it’s gonna happen.’ Whatever you say is what is. At that time, I said, ‘One day, I will play in that band.’”

Amp met Clinton’s chauffeur Adrian in 1984, when Clinton resided on the top floor of the then slightly shabby Book Cadillac Hotel, where he recorded music. Adrian passed Amp’s demos to Clinton, who immediately rang Amp up and offered the young musician a spot behind the keyboards vacated by Bernie Worrell. Amp would have to quickly learn P-Funk’s catalog, a daunting task.

Fortunately, he could read music, but Clinton and most of the band could not. While some of Amp’s bandmates took umbrage to his musical education, Clinton took pride in it.

“See, that’s where I painted myself in a corner,” Parker says. “I couldn’t read music, and neither could my heroes Hendrix, Jeff Beck, and Jimmy Page. They played by ear. So, I followed the mythos of playing by ear, thinking that’s all the education needed. But Amp — Amp was smart. He built his career based on education.”

Now, for a second time, Amp found himself a mentor, this time in the psychedelic guise of Clinton, who taught Amp about arranging, management, touring, and marketing. Amp also witnessed Clinton’s mercurial side. Clinton had his Rasputin moments when those pitch-black, sleep-deprived eyes bore right into you. Clinton, like Prince, didn’t tolerate fuckup and he instilled real fear in his musicians.

In 1989, Amp took a leave of absence from P-Funk for a recording contract, a reward he felt he deserved for his servitude. He enjoyed recording and jamming on stage with the other funkateers, but he felt trapped creatively and artistically aboard the P-Funk mothership. Having learned as much as he could from Clinton and P-Funk, Amp wanted to fly on his own wings, do his own thing.

Under the name of Mr. Fiddler, Amp and brother Bubz (by now a talented bass player in his own right) recorded With Respect on Elektra Records. Released in 1990, the album was a critical and commercial failure.

In reality, With Respect was a brilliant show-offy piece of record-making. Possibly, on this LP, Amp didn’t leave his ego at the door. His artistry was on full display, showcasing his musical hubris to dare replicate the sounds of Cab and Duke perfectly, while still keeping it funky. The critics were right when they said the album didn’t flow — it wasn’t supposed to. With Respect was Amp shouting at the world to notice him, the new virtuoso on the block.

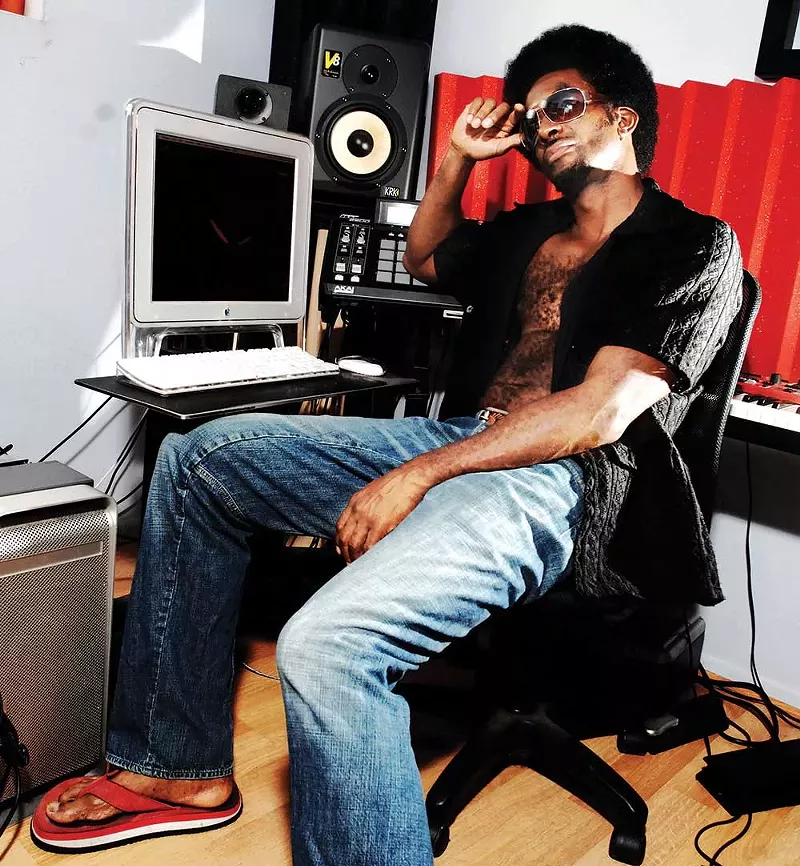

If the lack of sales bothered Amp, he didn’t show it. Perhaps he was content with the $10,000 Elektra advanced him, in addition to the promotional keyboard, synthesizers, and drum machine. Amp used the advance to build a recording studio in the home he shared with Bubz, which he later christened Camp Amp.

As much as Amp enjoyed collaborating with Bubz, his next collaboration would be one of his greatest. Dorian Anthony Fiddler was born from the collaboration between Amp and Stacey Willoughby, Dorian’s mother. From the absolute beginning, Dorian was the light of Amp’s life. Amp used a variety of music to lullaby his infant son to sleep — sometimes classical, other times jazz, with a smattering of rock in between. Music was a constant in the child’s life, and Amp, the proud Papa, took young Dorian everywhere. Early on, Amp mentored the boy, which gave Amp immense pleasure, but what made him even happier was watching Dorian’s musical progress as if Amp were learning all over again through the eyes of his son.

Dorian showed a keen interest in drums and percussion and by high school, he was a master at it. He even began mentoring his fellow bandmates. Both father and son wanted to please the other and nothing pleased them more than to perform together, which they did twice, once at Campus Martius and again at the North American International Auto Show. Both times, Dorian accompanied his Dad on drums. Similarly, Erin Davis, son of Miles Davis, played drums on stage with his famous father.

But fatherhood agreed with Amp, much more than Willoughby ever did. Shortly after Dorian’s birth, Amp fell out of love with his mother, and eventually, Willoughby quietly packed a bag and split. To Amp, Willoughby’s betrayal was simply fuel for his artistic fire. Meanwhile, Dorian worshipped his Dad for his musical brilliance and for Amp’s avant-garde style of dress.

Draped in tailor-made jumpsuits of his own design, Amp cut a striking figure, which landed him a cover photo on Hour magazine as one of the city’s best-dressed men. His clothes, like his music, were eclectic and defined him.

His style could also be seen, unintentionally, as a calling card for others in the industry — like the time in New York when a pair of the singer Maxwell’s handlers recognized Amp crossing the street by the apparel he wore at a show the night before. Although Amp hadn’t performed at the show, the handlers assumed correctly that Amp was indeed a musician. They asked him what instrument he played. Keyboards, he told them. The handlers gleefully told him that Maxwell, at that moment, was in search of a keyboardist, which is how Amp got the gig of keyboardist on the singer’s first LP.

Impressed by Amp’s artistry, Maxwell later invited Amp to play on his follow-up record. In L.A., singer Raphael Saadiq met Amp inside the Sunset Studios during a chance encounter. “I walked in and saw this tall brother in leather pants with an exploding Afro and an Egyptian Pharaoh-type of goatee walking out of the studio,” Saadiq says. “Everything about that cat spelled musician. I had to meet the brother.” In 2004, Amp played keyboards on Saadiq’s sophomore LP, Ray Ray, on the singer’s Pookie Entertainment record label.

Garry Green, a clotheshorse himself, often accompanied Amp to New York on fashion excursions. “Amp was on a first-name basis with every Black-owned haberdashery in Harlem,” he says. “We did our shopping in Harlem at small mom-and-pop boutiques. Amp would go to one boutique and buy a shirt, buy a pair of shoes at another one, and pants at yet another boutique. Amp bought clothes in unmatchable colors. When Amp put it all on, it came together, everything coordinated. The more unconventional the clothing, the better he looked. Now, that’s artistry.” Whenever Amp went on these shopping excursions, tours, or recording sessions, Dorian remained on Revere Street, under the supervision of his Aunt Deb and Uncle Bubz.

Throughout the ’90s and into the new millennium, Amp worked with a parade of the most innovative artists and DJs in the business: Prince, Seal, Moodymann, Jamiroquai, the Brand New Heavies, Fishbone, Sly & Robbie, Theo Parrish, Seal, Corinne Bailey Rae, Basement Jaxx, Scuba, Carl Craig, Will Sessions, and neo-soul singer Meshell Ndegeocello. Then, there was the high school student who was led to Amp’s front door Pied Piper-style by the music emanating loudly from the basement window of Amp’s studio.

The student’s name was James Dewitt Yancey. Across the street from Amp’s Revere Street residence sat Pershing High School, where James attended. After school, on his way home, he would hear Amp’s music and sometimes, James peeped Amp emerging from a tour bus, dropping the musician at his doorstep. This intrigued the young Pershing student, for James had yearnings of being a musician, specifically a rapper. He painstakingly made mixtapes on a cassette recorder in the basement of his mother’s home. Amp listened enthusiastically to the young student’s demo and invited James to Camp Amp.

Much has been written about Amp’s mentoring and grooming of the young artist, who would come to be known as the acclaimed producer J Dilla, such as Amp teaching Dilla the use of the Akai MPC60 sampling machine. Dilla formed the influential Detroit group Slum Village, and later, Amp introduced the nascent producer with rapper Q-Tip, a member of A Tribe Called Quest, when the Lollapalooza festival stopped in Detroit, where the P-Funk All Stars performed on the same bill as Tribe. Dilla went on to produce Tribe and Q-Tip’s solo LP, but not before penning several cuts for his mentor’s 2004 Waltz of a Ghetto Fly. (To learn more of the superstar rapper-producer’s musical journey, see Dan Charnas’s excellent 2022 biography Dilla Time.)

Ghetto Fly is a cool breeze of a LP, funky yet not P-Funky, with hints of Sly and the Family Stone, particularly when Amp’s voice goes into a raspy, reedy, growl à la Sly. Amp explained the album’s title in a 2004 NPR interview. “When I was kid, I used to see older guys walking down the street with a stride,” he said. “They were waltzing a certain way — neighborhood style, to get respect.” The Ghetto Fly title is a nod to Super Fly and Black exploitation flicks of the ’70s, and the LP was a commercial success, perhaps a bigger success in the U.K. than in the U.S. No longer a member of P-Funk, Amp became his own frontman. “Now I’m doing my own thing and it’s a beautiful world,” Amp said in the same NPR interview.

The discovery of Dilla made Amp a kingmaker in Detroit’s underground music scene. Now, everyone wanted to work with him, and he wanted to work with everyone. Amp performed at Campus Martius, promoting his third LP, the well-received Afro Strut. After the promotion, the musician moseyed over to an afterglow for Eric Roberson and Rahsaan Patterson, at the Jazz Café inside the Music Hall. “I was there as a favor to Monica Blaire, so I was introducing her to Eric Roberson,” Tombi Stewart remembers. “Going up the steps, my mother said she wanted to introduce me to someone she’d known. Amp saw me walking up the steps and said he wanted to be introduced to me as well. He said it with a big grin. So, I went up the steps, hoping he wouldn’t be there when I returned. I wasn’t interested. I was trying to give myself a break from the last relationship. I didn’t want to be bothered, but I said OK, if the brother is still there when I get back, I’ll give the brother a word. He was there in the same spot with the same grin. Now, I didn’t know who he was, and he didn’t know me, but I think he liked the fact that we shared so many mutual friends who approached us both at the event. People knew us. We wondered why we hadn’t met before, so we got to know each other.”

They talked for hours. She told him she was a multi-instrumentalist, namely a pianist. He said he liked old movies, comedies mostly. They spoke of heartache and break-up before the conversation turned to music, his and her likes and dislikes. Amp ended the conversation by asking for her email address.

“I wasn’t interested. I was trying to give myself a break from the last relationship. I didn’t want to be bothered, but I said OK, if the brother is still there when I get back, I’ll give the brother a word. He was there in the same spot with the same grin.”

tweet this

“Most people ask for a phone number, something conventional, but Amp wasn’t conventional,” she says. When she told him, Amp didn’t put the address in his phone. “I’ll remember it,” she remembers him telling her.

“I doubted that he would remember it. And I wouldn’t have cared if he didn’t,” Stewart says of their meet cute. Amp emailed her the next day. He was hosting the Roy Ayers show at MOCAD later and asked if she would like to attend as his guest.

“I didn’t go,” Stewart says “It was my father’s birthday. We emailed a lot. Exchanged cell numbers. We enjoyed talking on the phone. The more we talked on the phone, the more both of us realized how much we were alike, not in a shallow sense of having the same common interests. I saw him in me, a kindred spirit. Maybe he saw me in him, I dunno... But I still wouldn’t go out with him.”

Stewart and Amp hung out a few times before she eventually caught one of his shows, attending alone. “It was magical. Amp’s energy on stage was electrifying and magnetic,” she says. “He had everyone out of their chairs and on their feet. He was having fun as much as the audience and the audience could sense it. There was a lot of good will between them and Amp.”

It wasn’t long before Stewart became a regular at Camp Amp. Both Bubz and Dorian warmed up to the idea of Stewart being part of the equation. It had been a long time since a woman inhabited the Revere residence with any frequency, and her presence dissolved their My Three Sons aura. Amp appreciated Stewart. He valued her understanding of music and creativity, especially nurturing creativity. And she scribbled out lyrics. Stewart helped pen the lyrics on the album Inspiration Information, a joint effort of Amp and Sly & Robbie, the prolific Jamaican power producers. Mystic even supplied lyrics on the LP and sang background. A family affair indeed.

Released in 2008, Inspiration Information was a smash groove with both critics and audiences alike. Also that year, Amp received the Heineken Independent Achiever Award and the Soul Tracks Reader Choice Award for the Male Vocalist of the Year. But by the following year, Amp’s career would come to a crashing halt. On May 1, 2009, Dorian Fiddler died at age 18 of diabetic complications. Amp was beside himself with grief, as inconsolable as any father would be. His family gave as much support as they could give him and yet, it wasn’t enough to break him from his grieving. He cried. He blamed himself.

J Dilla’s death in 2006 had rocked him like an earthquake, but now felt like a tremor compared to Dorian. Although he had abandoned Catholicism years ago, the oppressive weight of Catholic guilt still hung over Amp like a shroud. In his guilt, Amp thought because music came easy to him, his son’s death was somehow the result of Amp’s success. It blocked him creatively. The music stopped. These were the dark times.

Stewart says, “I knew he needed the time to grieve, no matter how long, and I gave him the space to do it in.” Gradually, the musician crawled from under his shroud of guilt. He padded through the house quietly, in a haze. Whenever someone, family member or friend, asked him how he’s doing, Amp quoted the weather, “fair, partly cloudy.” Again, his family circled around their younger sibling, but to no avail.

George Michalski tuned and restored pianos. He loved the sound the piano made, the tinkling of ivory keys. Bespectacled and gray-haired, Michalski was hired by Amp to refurbish his baby grand, by now a family heirloom. Amp watched the old man fine-tuning and restoring the piano, lovingly and patiently, and noticed the pride and inner peace the restoration gave Michalski. Amp wanted what the old man had — inner peace. He made a deal with the piano tuner: Teach him the ways of piano tuning and restoring, and every piano Amp restored he would donate to a church, assisted living facility, school, or to underprivileged young ones.

Michalski agreed, surprised by the musician’s knack for learning. In no time, Amp fine-tuned as perfectly as Michalski taught him. Each piano he tuned restored Amp’s spirit. Together, Michalski and Amp donated over ten pianos, and in these acts of goodness, Amp found his joy. The music flowed again.

Someone else beside Michalski was responsible for Amp’s recovery: 6-year-old Chaka, son of songstress-songwriter Neco Redd, who later put a shine in Amp’s eyes.

Redd opened for Amp as part of the group Platinum Pied Pipers in 2004 at Saint Andrew’s Hall. “Until the show, I didn’t know who Amp was. I never heard of Amp Fiddler,” says Redd. “After the show, Amp and I met briefly. He said he liked my voice and before I could thank him, he was whisked off somewhere. In those days, he was always being whisked somewhere.”

Platinum band member Maestro phoned Redd the next day, telling her Amp wanted her to go on an upcoming tour with her as backup singer. She jumped at this chance and instructed Maestro to pass on her number to Amp as he had requested.

“That was in March 2004,” she says. “It wasn’t until June that I received a second call from Maestro. He said Amp had lost my number. I gave it to him again.”

Maestro told her Amp would call her that day.

“You hear this all the time in the business, the ‘I’m-gonna-call-you back line,’” she says. “Another trick of the trade is for the record producers to gush about how talented you are, what a great singer you are, and if you want the record, lose some weight. So, when Maestro said that Amp would call that day, I didn’t believe him. I worked in a salon as a nail tech and was up to elbows in tweezed eyebrows and didn’t have time for the run around. But Maestro insisted I answer the phone when Amp called.”

Later in the afternoon, Amp telephoned the singer. She answered and Amp pranked her, disguising his voice in a silly Monty Pythonesque twitter, for Amp had been a long-standing fan of the flying circus. Then he got around to business and invited Redd on his European tour.

“He pulled a Big Red on me, like in the movie Five Heartbeats,” she says. “‘I like your voice. I like your showmanship. Let’s make a deal,’ that kinda thing.”

Amp asked if she had a passport. Redd said she hadn’t. The tour was starting in a week and she knew it would be weeks before she would be granted one. Amp told her that she could have one expedited in less than a week, something he learned from George Clinton.

By late September, Amp, Redd, and the band started the first leg of what was supposed to be a seventeen-date tour. It turned into thirty days. First stop was Germany, where they played Berlin, then Heidelberg, and Mannheim.

In Mannheim, the grumbling began.

“It was about my weight,” Redd confesses. “True, in the beginning I missed a few notes, which naturally didn’t endear me to my bandmates. But mainly, it was my weight. The band didn’t believe I had the stamina to keep up.”

By the time the band reached London, things had come to a head. The musicians’ mutiny became personal. Now, the band ridiculed the singer on how she spent her wages.

“They said I was blowing my money,” she says. “I wasn’t blowing my money. I was buying gifts for my Mama, for family members, for everybody but me. I didn’t buy myself any, not one gift. The way I figured it, the tour was my gift.”

Amp got wind of the backstage brouhaha and lit into the gossipy musicians in a fury that would have made George Clinton proud. First, Amp told the entire band and engineers to shut the fuck up. It was nobody’s business how Redd spent her money, and he told them, as far as her weight was concerned, he didn’t see a problem. All he saw was a beautiful young lady with a beautiful voice.

Amp’s diatribe might have silenced the musicians, but it did little to alter their avoidance of the singer. Offstage, Redd was ostracized by the band. Her bandmates would pair up between shows for lunch, dinner, or for a little sightseeing, leaving Redd behind to her own devices. Even Amp was nowhere to be found during those off hours.

“I was sitting alone at a café when Amp stepped in,” she recalls. “He asked me why I was by myself. I told him why.”

“‘Not today,’” she remembered him telling her. “‘Get up. I wanna show you the sights.’”

Strolling through the streets of London, Amp told Redd of his times in Europe and how he was ostracized by the Funkadelics for the mistakes he made musically on stage.

Redd apologized for her onstage mishaps like hitting wrong notes and forgetting song lyrics. Sometimes, he forgot the songs he was supposed to sing.

“Have fun with it,” he told her. “The audience doesn’t know you messed up if you’re having fun.”

On Mayfair Street, Amp confessed to his being different; how he had always been different. As a child he preferred classical over soul music. Growing up, he wore hippie garb, like his influential sister Mystic. The neighborhood kids cursed him for the clothes he wore. Half a fag, they called him mostly. But thanks to his mother, he could be himself without fear or doubt of who he was, which enabled him to be exactly who he was.

“Neco,” he said as they crossed Binney Street. “You got this. You got this.”

“On every show, Amp gave the band thirteen minutes of solo time onstage,” she says. “I would dread those thirteen minutes. I struggled with this one song, my solo song, every night until I got to Ireland. I hit this one note. I didn’t sing off. Everybody in the band gasped in relief. I had finally got it. I remember Amp grinning at me the entire night and I knew he had taken me under his wing. He had my back. Amp was very patient with me. He nurtured me. He’s a nurturer, not a shouter, as some producers can be. Those stories he told me about himself gave me the confidence to be myself. Amp opened me up musically.”

Amp’s genius was his ability to see a person’s musical possibilities before they could. Like Svengali, Amp could draw them from their inhibitions to a level of excellence, knowing instantly a singer or musician’s weaknesses, as well as their strengths. Amp was a keen observer and with very few words corrected any problems they may have had.

“Amp was bigger than a movie star to me,” Redd says. “He was like the Dalai Lama, and the Europeans treated him as such. Everywhere we played they treated us like royalty. We ate like kings. Everything was lush. The tour bus we traveled on, the clubs we played in, the hotels, everything.”

To show how big Amp’s tour was in Europe, jazz legend Roy Ayers opened for Amp in Paris. It irked some in Ayers’s camp that he was an opener since Ayers was a bigger name in the U.S. than Amp. But in Europe, Amp was the headliner, not Ayers.

Overseas, Amp might have been King, but back home he watched his son die. The piano tuner, Michalski, only partly brought Amp out of his funk. Amp received the calm he needed from the older man to accept what had happened to Dorian and in turn absolve himself of blame. But something was needed to break through the sadness. He wasn’t sure what, though.

Then, Amp found it in Redd’s son. By this time, she was a regular on Revere Street and brought Chaka along on those visits. They became close friends, Amp and Redd, almost like family, watching basketball together on TV while Bubz barbecued in the backyard. Sometimes, the two would collaborate in the basement.

Amp took a shine to the six-year-old immediately. Bubz too. The two brothers held sleepovers for the boy, picked him up from school, and drove him to his football games, where they rooted him to victory. The brothers even cooked young Chaka Sunday dinners.

To some, Amp could be a closed book. Secretive. To Chaka, he wasn’t like that. He was as open to him as he was with Dorian. Amp often told Chaka’s mom how much her son reminded him of his son. “Chaka filled the void Dorian left,” Redd says.

Amp welcomed the extended family, especially since he was losing his own. He had lost his dad, then his mother, who had died in the early 2000s in her birth state of Virginia. Then Dorian. Mystic died in New York. Amp was there with Mystic when she died. Crushed by his sister’s death, Amp sat in Central Park afterward, remembering her kindness and guidance. Uncle Bubz followed in 2016. Amp regretted not collaborating more with his older brother. Charles died in 2018, and Deb after that in 2021. With grace, Amp endured the deaths, burying his grief in the music.

He managed to produce four albums: Motor City Booty in 2016, Kindred Live and Amp Dog Knights 2017, and The One in 2018. Then, in 2020, Amp received Kresge Artist Fellows grant.

Yet the albums and awards did little to assuage the cancer ravaging his body, a fact he had known for several year prior to his passing. Why Amp kept the disease discreet is ripe for speculation. Maybe because it was his secret to keep. Amp was in and out of the hospital for most of ’21 and ’22, playing the occasional show when he could do so.

In 2022, Amp performed three concerts. The first one was held at the DIA, the second one at the DSO, and the third, at the Dequindre Cut in July, was his last. The back-to-back shows meant rehearsals during the day and playing at night, which left Amp little time to rest between shows.

“Those concerts were the best I have ever seen,” Stewart recalls. “Amp was gaunt. He had lost weight, but his performance, his stamina and voice were super strong. It was amazing, even Amp said so.”

Amp’s doctors, Jeffery Mensah and Sheba Roy, found Amp amazing as well. Dr. Roy wept the night she caught Amp’s show at the DIA, overwhelmed by the musician’s endurance.

Stewart accompanied Amp to Ascension St. John’s Hospital a few days after the Dequindre Cut show. Overnight, Stewart became Amp’s Florence Nightingale, his bodyguard, the keeper of the proverbial flame. “I was there by his side unconditionally,” Stewart says. “I was there advocating for the correct medical treatment, helping Amp to make the proper medical decisions, coordinating with the advice of Doctors Mensah and Roy. This level of caretaking was much more extensive & complex than what I’d experienced before. Yet, somehow, everything came together.” Slender and beautiful, Stewart seemed more comfortable on a fashion runway than as someone’s caretaker, but Stewart proved to be more than capable of the job.

Stewart rarely left his side. When needed, a number of Amp’s close friends would fill in. Stewart turned Amp’s hospital room into a sanctuary of calmness and clarity, soothing the musician with courage, positivity, and most of all love, even with him slowly slipping away in front of her eyes.

Around Christmas, Amp was no longer in his hospital room, but inside the belly of a shimmering gold satellite, the size of a mothership, which at first, he thought he was on, except the music he heard was all wrong. It wasn’t P-Funk he heard echoing through the cavernous corridor. Bubz, he said to himself, recognizing the sound of a thumping bass guitar.

Amp stepped inside a glittering ballroom, and with great delight he saw his family, all dressed in white, Bubz on bass, accompanied by Dorian on drums, and Charles on alto sax. Mystic sang back up. Amp looked at his parents beaming from the sidelines. Now, Amp found himself draped in white, the color of lamb’s wool. Grinning, Amp slipped behind the baby grand and joined in.

Editor’s note: The original version of the article misspelled the names of Fiddler’s sister Deborah, Stacey Willoughby, and Monica Blaire. There were also some chronology errors, and those who knew Fiddler say he did in fact play the harmonica. The corrections have been made to the online version.