Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Drummer Gayelynn McKinney — who you may know from her all-women jazz group Straight Ahead, or her recent work with Aretha Franklin — grew up in a magical place for musical development to be nurtured: the home of beloved Detroit pianist, composer, educator, and Tribe member Harold McKinney.

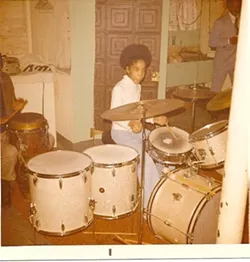

McKinney's mother, the late Gwendolyn Shepherd McKinney, was an accomplished musician herself — an opera singer before "Dad sucked her into jazz," Gayelynn recalls mischievously. It was Gwendolyn that bought McKinney her first drumset at age 2.

Tribe Records, which also published a magazine, was an artist-run collective based out of Detroit that was active during the '70s. Among its members, it counted Wendell Harrison, Phil Ranelin, Marcus Belgrave, Doug Hammond, and of course Harold McKinney.

Only eight proper albums were released during Tribe's too-brief existence, but all of them are more or less fantastic. Of these, Harold McKinney's sole release on the label is 1974's Voices and Rhythms of the Creative Profile, a funky, soul-jazz delight. Gayelynn remembers being in the studio, abuzz with curiosity during the recording sessions and fascinated by Darryl Dybka's Moog, the first synthesizer she had ever seen.

McKinFolk is a project that was begun by Harold, but Gayelynn is preserving the name and keeping the concept alive by leading her version of the group now, with a new record coming out soon on Detroit Music Factory called McKinFolk: The New Beginning. The tracks on the album are a rich mix of her father's compositions throughout the years, with the sole exception being "Freedom Jazz Dance," the original itself a cover of the Eddie Harris composition made famous by Miles Davis.

Harold's version of "Freedom Jazz Dance" is a spirited take, spaced up a bit with some Moog. Gayelynn gives the track the same treatment in her own style, preserving that ever-memorable Moog. A handful of songs from the 1974 Tribe release appear on the upcoming McKinFolk album, including "Ode to Africa," which features a sound clip of a young Gayelynn speaking with her father during their daily philosophical talks, and "Heavenease," which is actually a song that Harold wrote about Gayelynn.

Gayelynn says when she was 1 or 2, she was looking up at him and babbling something, and it really looked like she was trying to communicate. After that, a song started flowing into his head. That song became "Heavenease." Gayelynn's version features her aunt on flute and her young niece speaking in "baby talk" at the beginning. Her father and mother both sang on the original, making this one an especially McKinney-heavy piece.

In advance of McKinFolk's upcoming Jazz Fest performance, which includes a Detroit dream team personnel, we spoke with Gayelynn about memories of growing up surrounded by music, youthful encounters with jazz legends, and more.

Metro Times: Who is in your version of McKinFolk?

Gayelynn McKinney: The thing about McKinFolk is that it's made up of movable parts. Next time you see the group it may be a different set of people. But on this run, at the festival, I'm delighted to have Dwight Adams, Marcus Elliot, Vincent Chandler, Marion Hayden, Glenn Tucker, Michelle McKinney, my second mama, on vocals, and special guest Regina Carter.

MT: Your father was heavily involved in Tribe, for one, and music all his life. What was it like growing up in that environment?

McKinney: I feel really blessed, because both of my parents were musicians. My mother was a part of Tribe, too. Every morning I woke up to music. It was a mixture of music too, because my father would be wailing away, working on a composition, so I'd hear him playing this beautiful jazz piano, and my mother, who had started out as an opera singer, would be in the kitchen singing songs from Carmen. I would wake up to this every morning, and after breakfast, Dad and I would have what we called philosophical conversations. He did this with me from the time I was at least 9.

Growing up in that environment, Wendell Harrison and Marcus Belgrave and George Davidson, all those guys, were rehearsing at Dad's house almost every day, so my house was filled with music from sunup to sundown. They would come over and rehearse, and they were very passionate about the music. Especially Dad and Marcus, they would get into some heated conversations about the music, and then after they would get all of that out of their systems, they would play, and it would just be fantastic.

It was a musical playground for me, running from one place to the other, looking at music and playing drums. Ed Gooch used to bring his trombone over to the house so I could play with it while they rehearsed, so I was in the basement playing his trombone. I got the chance to play a lot of different instruments growing up. It was great, a wonderful experience.

MT: What set you up on drums as your main instrument?

McKinney: My mother said I was extremely busy when she was pregnant with me, I was always moving around. As soon as I can remember I was tapping and beating on things. My mother bought me a drumset and said, "Here honey, beat on these." [Laughs.] So I started beating on the drums at about 2 years old. I sat up under musicians that came to the house. The first drummer Dad had was Jimmy Allen [who also played with Sam Sanders], and I used to sit at his feet and look at everything he was doing. After him, George Davidson [Tribe, Strata, and more] came into the picture when I was about 5 or 6, and I stayed by his side. In fact, George says that he was always worried about getting my nose caught up in the hi-hat cymbals because I sat so close. [Laughs.] I had to see what his hands and feet were doing. I wanted to see everything. When he left, as soon as he got in the car and turned the corner, I would jump on his drums and play them.

‘As soon as I can remember I was tapping and beating on things. My mother bought me a drumset and said, “Here honey, beat on these.”’

tweet this

Dad had all these drummers coming through the house, but one in particular had a big influence on my playing, along with George. He came into the house one day, and I didn't recognize him. I knew all the drummers that came through the house and this guy I didn't know. He was tall and had this wonderful stick bag in his hand. I thought, 'Oh, he's a drummer.' I went over and followed behind him. He sat down, threw the stick bag on the table, opened it up, and laid it out. He had a pair of red drumsticks, like a natural wood reddish color, that fascinated me. I was looking at those sticks, and I looked at him, and I sat really close next to him. I tapped him on his shoulder and I said, "Hi." He looked at me but didn't say anything, he just smiled. I said, "Can I have those sticks?" [Laughs.] He said, "You want my sticks?" I said, "Yes. Can I have those?" He said, "What are you gonna do with my sticks?" I said, "I'm going to play with them." He said, "Hm. Alright. I'll tell you what, I want you to listen to me first." I said, "OK." So he said to me, "I want you to remember the melodies of every song."

I looked at him, my face scrunched up, and I said, "Why?" He said, "Because if you remember the melodies, people will know where you are when you solo." I was mulling that over in my head, and there was a moment of silence, and then I tapped him on the shoulder and said, "Hey, can I have those sticks?" [Laughs.] And he said, "Go on, girl — take these sticks and go!"

Fast forward 10 years later, I'm starting to check out the players and who's doing what. My friend and I are sitting there looking through this jazz book, and we get to this page and I stop and say, "Oh wow, that's the guy!" My friend said, "What guy?" I said, "That's the guy that gave me those drumsticks!" My friend said, "Get out of here, that's not the guy." I said, "Seriously. When I was 10 years old, he gave me some drumsticks." It turned out that that guy was Max Roach.

Max Roach gave me a pair of sticks and told me the most valuable information I could have ever received to shape my playing. When Straight Ahead got signed to Atlantic Records, we ended up opening for him at the Fillmore, when it used to be the State Theater. At the sound check, I walked over to him, and by now it must have been 12 or 13 years later, but I walked up to him and said, "I don't know if you'll remember me," and he said, "Oh, I know who you are." I said, "Really?" He said, "Oh yeah. You're that little girl that took my drumsticks."

I met people and didn't realize who they were until much later. Herbie Hancock [is another person] I met and didn't realize [who he was] until I was older. It was quite an environment to grow up in.

MT: Speaking of Herbie Hancock, what can people expect out of the performance at Jazz Fest?

McKinney: You're gonna hear some of my father's great compositions and have a good time just listening to the interpretations of his music. It'll be a little bit of funkiness, definitely some swinging-ness, and some wonderful, beautiful ballads that he wrote.

McKinFolk performs on the JPMorgan Chase Main Stage from 2 p.m. to 3:15 p.m. on Saturday, Sept. 2 during Detroit Jazz Festival in Hart Plaza, Detroit; detroitjazzfest.org; Admission is free.