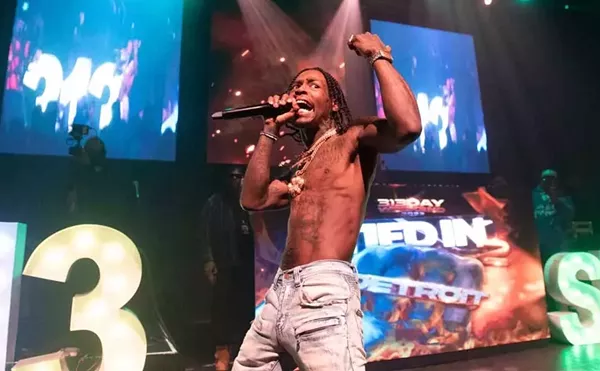

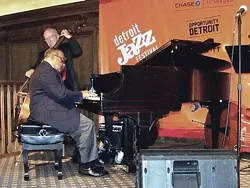

It was 45 minutes before their set was to start when the four members of the Charles Boles Quartet began warming up in the musicians’ lounge at the Dirty Dog Jazz Café on a recent Tuesday evening.

Ron English, his guitar slung over his shoulder, goes over the set list. He plans to opens with Charlie Parker’s “Quasimodo” and Horace Silver’s classic “Song for My Father,” concluding with a Boles original. Bassist John Dana plucks some bottom notes from his upright. Drummer Renell Gonsalves slides out front to ready his drum kit.

Boles, the eponymous lead musician, sits at a table talking to a local music reporter. This is all too familiar for the 80-year-old jazz pianist — a reporter picking his brain about Detroit’s vast jazz history — and how Boles figures into it.

Boles is one of the remaining Detroit bebop pianists from an era that included greats such as Tommy Flanagan, Sir Roland Hanna, Barry Harris, Hank Jones and the recently departed Claude Black.

On this Tuesday, Boles is still around to talk about his career, which spans six decades. He’s played steadily since 1947, except for a one-year convalescence after a life-threatening heart attack.

Boles is short, outspoken and blessed with genteel manners and a reputation as a first-rate storyteller. And Boles is full of stories. He tells of the time he tracked down his boyhood hero, jazz pianist Erroll Garner, who was staying at a hotel in Detroit. Boles booked a room at the hotel, although he couldn’t afford it — so he could meet Garner. He did meet Garner, but got less than he hoped for his investment. The dazzling pianist and composer of “Misty” was, according to Boles, a windbag who talked two hours straight about himself. Then there’s the time Boles declined a lucrative gig in China, fearful his loose tongue and political view would get him locked up.

On the piano, Boles compresses decades of African-American music — from gospel and blues to bop — into a single set. Boles’ playing is more about elegance than improvisation.

The jazz great grew up in Detroit. He lived in an orphanage until the Boles family adopted him as a 4-year-old. The Boleses were a family of pianists, and his adoptive mother was related to the famous stride pianist Fats Waller, who encouraged her to get the young Boles piano lessons.

At Northern High School, Boles was part of the famous seventh-hour jam sessions that included future jazz stars Tommy Flanagan, Donald Byrd, Sonny Red and Paul Chambers. Back then, there were many places for young musicians to play, and Boles took full advantage. All this jamming had a negative impact on Boles’ high school studies. He didn’t graduate until he was 20 years old.

Immediately after graduation, Boles toured with the R&B band Emmitt Slay & his Slayriders. The band played mostly U.S. Army bases. When Boles returned to Detroit, he worked regularly on Hastings Street; to make ends meet he sold insurance and worked at a car wash.

That workload took a physical toll on Boles, who had a heart attack at 28. He was sidelined a year. Once he recovered, he says he decided to play music exclusively.

Boles toured with a young Aretha Franklin as her musical director. He worked with the legendary female comic Moms Mabley, and toured nationally and internationally with B.B. King. When Boles stopped touring, he landed steady work back in Detroit — first at the Playboy Club and then lengthy stints at the Roostertail and the Troy Marriott.

Many of Boles’ boyhood friends had become jazz stars. Barry Harris and Tommy Flanagan encouraged Boles to join them in New York. They found him a place to live and guaranteed him steady work. Boles relocated for a year. Then he returned to Detroit. He wanted more long-term security.

“I wanted to be able to retire. When I call Barry, he’s always has to call me back because he’s on his way to Japan. I didn’t want to be an 80-year-old and have to tour,” Boles says.

Boles taught at a program called Metro Arts at Northern High School in the city and at Oakland University. Thankfully, the musician saved enough money for retirement.

Boles didn’t record as much as his friends though. Harris and Flanagan recorded for some prestigious jazz record labels. Flanagan recorded scores of discs right up to his death, and Harris had a new release as recently as 2010. Boles only recorded once as a bandleader, part of a 4-disc compilation of material from the early years of the Montreux-Detroit Jazz Festival. As a sideman, Boles only recorded with B.B. King.

“Now that I think about it, recording wasn’t really that important to me,” Boles says.

The manager of the Dirty Dog appears at the lounge door and informs Boles it’s getting near show time. For a year at this swanky jazz spot, the quartet has been a popular attraction, playing swing, bebop, hard bop, blues, even R&B if the spirit hits them.

Asked whether the key to longevity is playing jazz, Boles says there isn’t one. He made up his mind long ago to play the piano, which was how he wanted to make his mark, and he has stayed true to that.

“When I started playing the piano professionally in 1947, I never imagined I’d still be playing it in 2013. That’s amazing,” he says.

Charles Latimer writes about jazz for Metro Times. Send comments to [email protected].