How the NBA’s John Salley gave Detroit hip-hop producer J Dilla his first big break

An excerpt from the new book ‘Dilla Time: The Life and Afterlife of J Dilla, the Hip-Hop Producer Who Reinvented Rhythm’

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

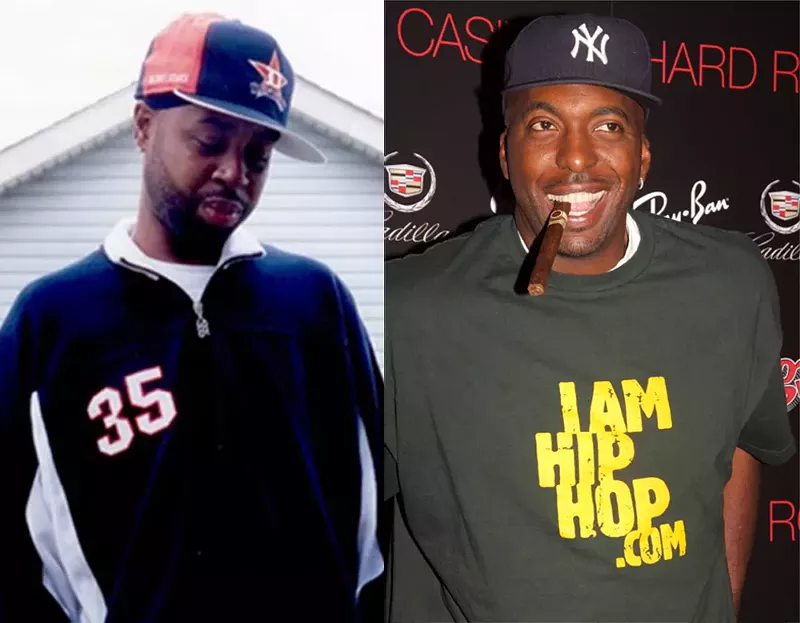

A new book — Dilla Time: The Life and Afterlife of J Dilla, the Hip-Hop Producer Who Reinvented Rhythm, out now on MCD/Farrar, Straus, Giroux — chronicles the life and legacy of James DeWitt Yancey, the influential rapper and producer from Detroit whose promising career was cut short when he died in 2006 at age 32 following a battle with a rare blood disease. In this excerpt, shared exclusively with Metro Times, Yancey and his partner T3, then two-thirds of Detroit hip-hop group Slum Village, link up with NBA player John Salley and producer R.J. Rice to get Slum Village a record deal.

Yancey and T3 saw commercials on WGPR-TV’s New Dance Show in 1991 advertising Hoops, a recording studio founded by the Detroit Pistons power forward John Salley. Word spread among Detroit’s aspiring musicians, singers, producers, and rappers that the basketball star was starting a label of the same name, and that he was hunting for artists.

Detroit loved Salley because Salley loved Detroit. The role of “The Spider” in the Pistons’ recent championship streak aside, he made his home in the city, not the suburbs; and he invested in local businesses. Salley was convinced that even though Motown Records was long gone, the talent that made Motown possible was still here in Detroit. But Salley knew next to nothing about the music industry. For that expertise, he turned to a local producer named R. J. Rice.

Nearly everyone who came up in Detroit in James’s generation had danced to “Shackles,” by Rice’s Latest Arrival, a group produced by Rice and featuring his wife, DeDe, on vocals. A progressive dance classic, “Shackles” was one of the few records out of 1980s Detroit to break nationwide, the song rising to No. 6 on the Billboard R&B chart in 1984. The road to that hit, and back from it, had been rocky. Ralph James Rice had been driving it since 1979, releasing a dozen different singles and three different albums — each titled R. J.’s Latest Arrival — before “Shackles” blew up. A major deal with Atlantic Records fizzled when his follow-up singles stalled just shy of the top ten; and his next relationship, with EMI Records, was plagued by corporate restructuring and the market’s sharp turn toward hip-hop, from synthesized to sampled sounds. Rice had learned that a record contract was a slippery thing, the words on paper mattered less than the relationships behind them. Sometimes executives did deals just to stand next to people who made them look good. If you weren’t making them money or making them look good, your deal was done.

By 1990, R. J. Rice was looking to stay closer to home. He and DeDe had a child now. He wanted to build a recording studio, but the loan officers at First Independence Bank told him that the music business was far too risky for their tastes. Rice pondered the implications: the biggest Black-owned bank in the birthplace of Motown Records, P-Funk, and techno, declaring that Detroit music had no future. When Rice was introduced to John Salley shortly thereafter by their mutual accountant, everything turned around. First Independence was suddenly happy to extend over a quarter-million dollars in loans. Sometimes the money mattered less than who folks wanted to stand next to. Salley looked at Rice’s utilitarian Dodge Raider. If you want to stand next to me, Salley told him, you need to get a new car.

Rice was not used to his partner’s extravagance. Salley remodeled a grand old bank building in Oak Park and put a recording studio in the vault. He bought custom-made desks and chairs. He bought TV and radio spots. He brought in his childhood friend Michael Christian to scout talent. And Hoops opened its doors to a new generation of Detroit artists.

When Yancey and T3 showed up with a tape in their hands — the rooms lit in purple and thick with the smell of air freshener — they met Christian, who called Salley down to Hoops: You gotta hear these kids. Salley loved the Slum Village demo on first listen. Rice didn’t know what to make of them. After Salley escorted the two hopefuls back to the vault where Rice sat, Rice listened to James and T3, both of them stuttering from anxiety. Then Rice listened to their tape. They were stuttering on the tape, too. Maybe, Rice thought, this is the style?

Rice showed James their equipment — including an E-mu SP-1200 drum machine — in a studio that far surpassed anything in Amp Fiddler’s basement. In short order, Slum Village became a part of Salley and Rice’s Hoops roster, which came to include R&B singer-songwriter Tony Rich; local hip-hop group Dope-A-Delic; a foul-mouthed quartet of child rappers called Kid Je’ Not (pronounced “kid ya’ not”) that included Rice’s son, Young R. J.; and Rhythm Cartel, a duo of white MCs from the Detroit suburbs — one skinny, one heavy. The latter of the two, a towering, boulder-sized teen, had acquired his own nickname, “Paul Bunyan,” on account of his resemblance to that mythical Midwestern lumberjack, but his real name was Paul Rosenberg.

John Salley used his celebrity and R. J. Rice his industry connections to bring the Slum Village demo to record companies in New York. Salley met with executives at Def Jam, Atlantic, and MCA, touting James as “the next Pete Rock.” Within a few months Slum Village was offered a deal by a new label, Pendulum, funded by Warner Music. When it came time to negotiate, John Salley asked Rice to step aside.

“Let me do it,” he said. “Nobody will lowball me.”

But Pendulum’s offer for the group did come in too low for John Salley, and nothing he said could get it any higher. Salley didn’t want to just give Slum Village away, so he balked, and Pendulum ended up signing another offbeat rap group, Digable Planets. Rice delivered the bad news to Yancey and T3. They were furious with Salley for rejecting the offer without consulting them, but by now the whole Hoops situation was bad news.

The press raved about Salley’s numerous business ventures: a sportswear shop, Funkee Flava, and an erotic boutique, Condomart. The TV host Robin Leach came to Hoops and to Salley’s fifty-two-room mansion to film an episode of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. But Salley had a full-time job in the NBA and couldn’t pay attention to the details. He discovered that the contractor they hired to build the studio had been double-ordering materials and sticking Hoops with the bill. Rice socked the contractor in the face, but the money was gone regardless. The partners had different creative visions: Salley had no use for the older-style R&B that Rice liked, and Rice didn’t much care for all the little rap groups that Salley was signing. He respected Slum’s talent; but talent didn’t sell records, hooks did. Salley and his artists got used to hearing Rice’s skeptical rejoinder to any music they played for him: But is it a hit, dawg?

This wasn’t a side hustle or hobby for Rice. He had a wife and a kid to support. When Rice could practically feel the creditors knocking at the door of their refurbished bank, he began quietly moving equipment out of the vault. By the time the real bank, First Independence, sued Salley and Hoops for defaulting on $325,000 in loans in 1993, Salley had been traded to the Miami Heat, and Rice was working out of his house. Salley had guaranteed the loans personally and was stuck with the bill. He would later comment that it took him many years and a meditation retreat to Costa Rica to forgive his former accountant and erstwhile partner; but that he never regretted advocating for Yancey. He just had a feeling that the kid was going places.

Excerpted from Dilla Time: The Life and Afterlife of J Dilla, the Hip-Hop Producer Who Reinvented Rhythm by Dan Charnas. Published by MCD an imprint of Farrar, Straus, and Giroux Feb. 1, 2022. Copyright © 2022 by Dan Charnas. All rights reserved.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Reddit.