Grande Ballroom documentary finds Wayne Kramer back on stage and bringing guitars to the Saginaw Regional Correctional Facility

Live'r than you'll ever be

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

You don't have to dig too deeply into the archives of Metro Times to find coverage of Tony D'Annunzio and his 2012 documentary Louder than Love: The Grande Ballroom Story, on Detroit's legendary late '60s music hall.

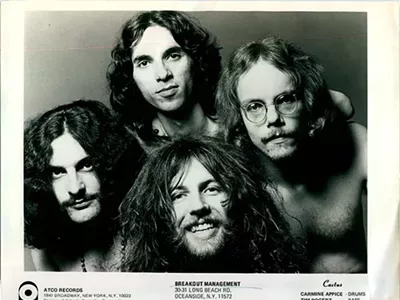

The film documents the music and culture surrounding the onetime dance hall (in the 1920s), mattress warehouse (in the '50s), psychedelic venue (1966-'72), and current ruin. You can still drive by it, at 8952 Grand River Ave., in the Petoskey-Otsego neighborhood. The spot's been closed for 40-plus years, but its lore rings loud and clear, so much that the idea of a feature film about a building does not seem strange or boring. After all, this was where the MC5's magnetic first album was recorded live, where the best local acts (Rationals, Frost, SRC) opened for international artists (the Who, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd) and often kicked their asses. Top blues and jazz artists (Howlin' Wolf, BB King, John Coltrane) were paired freely with those rock musicians, all of it artfully promoted in posters by Gary Grimshaw and Carl Lundgren.

You probably know all that stuff, though. Because while the story of the Grande was once among the great untold Detroit stories, it has been told, now. For music clearance reasons, it's not that easy to see the film; it's not on DVD or Netflix, so one has to wait for a special showing. And this Thursday, April 9, there will certainly be a special showing at the DIA's Detroit Film Theatre, as Wayne Kramer joins the Howling Diablos to play live accompaniment to the film as part of Art X Detroit. We caught up with D'Annunzio by phone to talk about all this exciting stuff.

Metro Times: How did this Art X event come about?

Tony D'Annunzio: I was selected last year as one of the Kresge Foundation's film and theater fellows. That was brought on because of the work I've done in film and theater here in Detroit over the last 25 years, including of course the Grande Ballroom film. As a part of the fellowship, they have this festival.

So they asked about submitting a project. As a filmmaker, I thought it was a great opportunity. But I couldn't see myself finishing a film I would be proud to show that I started in August. They had venues lined up, and then it was just put upon each individual what they wanted to do.

I always thought that my film, as much as I loved showing it, I thought it would be really cool to have a film with a live music element to it. Not in the sense of a silent movie where the band plays all the music, but just the interaction between it. My film is about the Grande Ballroom, so it's about rock 'n' roll, including that era of rock outside of Detroit — the Who and Cream, stuff like that. I had done an event with [MC5 guitarist] Wayne Kramer where he spoke about his nonprofit Jail Guitar Doors, which brings music workshops and donates instruments to prisons. When he got up to talk about it, I could hear the commitment and passion, I could hear what he wanted to do. And then it dawned on me: I've got this great opportunity to bring Jail Guitar Doors here. And although it's been to 40-something prisons around the country and a couple in the U.K., it hasn't been to Michigan yet.

MT: When I read that, I couldn't believe it.

D'Annunzio: I couldn't believe it either. Wayne and his wife, Margaret, who is also his manager, told me, "You know, Tony, it's really cool that you want to get behind this, but it takes years to get in these prison systems; it's not like making a couple phone calls." That was a challenge to me, because I felt, if they're saying I can't do it, I have to do this. You know? I found out that the University of Michigan has a pretty amazing nonprofit called the Prison Creative Arts Program, which was established in the '90s. I reached out to them to see if they would be interested, and spoke with Ashley Lucas, the director of the program. And she was telling me what they've done over their history, and how they've really been concentrating more on performance art and the written word. So I was telling her about Wayne's charity work and she said they really didn't have a music part of the program. The bells went off and I set up a conference call between the two organizations. There was this weird hesitation on both sides, because it just seemed too simple. Wayne wants to come to Michigan, and the University of Michigan wants music? On top of it I've got this great event that could roll out this program and give it a good initial push to tip the awareness? People here are aware of Wayne, but I don't think they know Jail Guitar Doors, and what he's been working on for years now, with it.

MT: I first heard of Jail Guitar Doors from a friend in New York who'd recently made a chunk of money and told me how he had made a donation. And earlier we'd been talking about local techno artists, all of whom seem to make the bulk of their money performing overseas.

D'Annunzio: Isn't that the truth? People come from all over the world to it, and some Detroiters find a way of avoiding it. That holds true for a lot of Detroit stuff. We've got incredibly great musicians and artists. But I think because they're so accessible we take it for granted.

My film was in 35 different festivals over the last few years. And the biggest thing I saw was the acceptance outside of Detroit for this obviously Detroit story. When you could take it to these festivals in L.A. or London, or even Tampa and San Francisco, places totally removed from Detroit, and the story resonates there, that was something. That era I encapsulate, the '60s and '70s era, is when Detroit was strong, 2 million strong. A lot of those people migrated around the world, and they've been telling the story of the Grande to their people. When I would come into another city, I would find it sold out and there would be a dozen people who'd come up and say, "You know what? I went to the Grande, but then I moved from Detroit to L.A. and I've been telling this story, but no one believes me." It's amazing to be the ambassador to this story. It was a tumultuous time in Detroit and for people to remember the Grande as a place of creativity and fun and music is a really cool thing.

MT: How will you incorporate the songs, the music, into playing along with your documentary at this show? Are they also doing incidental soundtrack stuff? Is there a score?

D'Annunzio: That's a great question. The musical direction is actually from Johnny Evans of the Howling Diablos. As it turns out, he was actually one of the judges for the Kresge Foundation. What we decided to do was, since the film is set up in chapters because there are these transition points in the film, and during these points, the film will stop, and the band will play on the stage for a few songs. And while they are playing, a re-creation of the original psychedelic light show will be shown up on the screen. Because when I was putting the film together, I shot these re-creations.

MT: Who did the light shows for the Grande?

D'Annunzio: This guy was one of the originals; his name is Clyde Blair. He and a fellow named Chad Hines were the ones who really got engrossed in it. They were graphic artists themselves and their stuff is amazing. I couldn't find any footage of the original light shows, so I thought, let me get a hold of these guys and let them recreate it. We took them into the studio and shot two or three hours of them just doing all this trippy stuff with different lenses.

MT: So, the day after this screening with the live band, you visit a jail?

D'Annunzio: Fender sent us nine brand-new Fender acoustics; Wayne is sponsored by Fender, has his own model of guitar with them or whatever. We'll take those guitars on April 10 to the [Saginaw Regional Correctional Facility], and Wayne will do a "call to action." They've got inmates ready. I've never been to one of his calls to action, but I know we're providing something for inmates that they normally wouldn't get. This shouldn't happen this quickly so I'm proud that I got everyone together to do this. It's humbling going into the prison — it ain't a joke. I'm hoping that this is going to be one of many prisons that allows for this.

MT: The guitars will stay there?

D'Annunzio: The reason that we were able to get into the Saginaw jail was because they have space for a lockup for these. That's one of the big things, and I think it's one of the reasons it's been so hard to get the program going elsewhere. I just read that there's a prison in California where inmates are recording and releasing their own albums.

MT: Is there talk of leaving a copy of your film there too?

D'Annunzio: At the prison? No, that wasn't even a consideration. To me, it was letting Wayne and the prison arts people do their thing. That's a good idea though — I hadn't thought of it!

Starts at 9 p.m. on Thursday, April 9; Detroit Film Theatre; 5200 Woodward Ave., Detroit; artxdetroit.com; event is free, but online registration is required to attend. On Friday, April 10, Kramer appears at the "Rethinking Justice" panel at MOCAD, alongside formerly incarcerated author Shaka Senghor, and Ashley Lucas from the Prison Creative Arts Program. Starts at noon; 4454 Woodward Ave., Detroit; 313-832-6622; mocadetroit.org; event is free.