Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

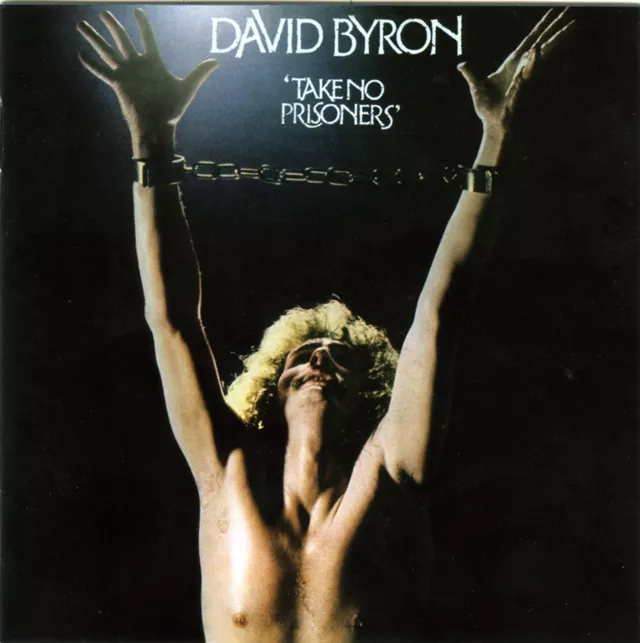

The rock 'n' roll heap is piled high with never-wases, burnouts, has-beens and straight-up tragedies. File singer David Byron in the latter, his fame equal parts salve and curse. He sold 30 million albums fronting Uriah Heep in the '70s, earned countless gold records and headlined arenas the world over. He drank himself dead in early '85 once his wife, most friends and fans had abandoned him — even his funeral was sparsely attended. There was arguably no greater fall in rock, and it's hard to imagine the once superstar dying alone, his body discovered later. After attempted comebacks, a lost mansion and fortune, Byron became a kind of rock 'n' roll Norma Desmond, tortured by ideas of a normalized, post-fame reality.

(Alice Cooper's life eerily paralleled Byron's then; Cooper was drinking himself to death and, by 1983, his career was finished; he was living far from his old Beverly Hills house, drunk in Scottsdale, Arizona — his aging Rolls Royce the metaphor; it showed dents, missing hubcaps and would stall at lights. Cooper, of course, sobered up and staged a Herculean comeback, scoring his biggest-selling single in 1989. Byron died too soon to ride the international hard-rock resurgence.)

This 1975 album — out a year before Heep booted Byron for being an out-of-control libationist rock star— is, despite the era's critical opinion, surprisingly good in context, great even, like Cooper's same-year solo debut, Welcome to My Nightmare.

Unlike the Coop though, critics abhorred Byron and Heep — mostly for Ken Hensley's too-often banal, pretentious songwriting — and the frizzy-headed front man, in his unfortunate satin shirts, Harry Reams 'stache and Icarus hubris, couldn't have seen the Damned, Clash and Sex Pistols around the corner.

Beyond the glam-disco élan, Byron had real range as a writer, singer and style interpreter, and Prisoners has aged much, much better than any Heep album and most mid-'70s rock records. Byron mercifully restrains his Heepster vocal histrionics and proves he was too lazily dismissed as a shallow singer; his skills and personality were potent enough to sustain a solo career.

The album's dark-pop opener, "Man Full of Yesterdays," merges organ drones and a soaring guitar hook with Byron's chilling slide-to-oblivion prophecy — though it was written as an ode to OD'd Heep bassist Gary Thain.

Suzi Quatro could've hit on "Sweet Rock 'n' Roll," a '70s classic-rock "spiritual" cloaked in gospel choruses; and you'd swear Stevie Wonder organist Clarence Bell propels the infuriatingly catchy "Steamin' Along," a prime piece of white-boy funk-rock, albeit with dirty rock compulsions.

"Stop (Think What You're Doing)" mixes '50s rock 'n' roll with beautiful overproduction, and the Mellotron-loaded "Love Song" certified Byron's considerable pop-crooner skills — tender, breathy dynamics with sexual tension for girls — a killer cross of Alice Cooper and David Cassidy. Album-best "Silver White Man" features singsong choruses with sweet "Ruby Tuesday"-like "Ew-la-Ew-la-las."

(The CD remaster includes an alternate version of that song plus a single edit and an out-take of others.)

The album's guests included some Heep alum, such as undersung, punk-riff guitarist Mick Box, and Moet & Chandon, Remy Martin and Mateus Rose are all credited. Prisoners is remarkable artifact to lost era when rock star excess was still counterculture ritual whose downside had yet to be defined on grand scales. It showed a man who'd no idea he was at his peak, in his life, in his career. —Brian Smith