Black History 101 Mobile Museum debuts

How rapper Khalid El-Hakim founded his mobile black history museum

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Detroit’s Fisher building is buzzing with the afternoon’s murmur: security guard footsteps, couples with coffee, and a class of high-schoolers taking notes and photos of the building’s art deco structures. They point, they click, and they chit-chat as a gray-haired woman with glasses riding the tip of her nose facilitates.

“That’s how history is kept alive right there,” says Khalid El-Hakim looking toward the group. “This building is over 80 years old, and people still come down here to take pictures.”

El-Hakim, 44, is the founder and CEO of the Black History 101 Mobile Museum, a collection of 7,000 historical artifacts ranging from slavery to hip-hop that has seen the inside of universities and galleries in 23 different states and two countries. The collection has gone from a storage facility to a tricked-out trailer to a permanent home at Detroit’s 5e Gallery. The Mumford graduate, who grew up collecting cards and comics, stumbled onto his passion while at Ferris State University in 1991.

“My sociology professor, Dr. David Pilgrim, brought in a racist piggy bank called a Jolly Nigger Bank,” he says. “The class was floored. Most of us had never seen anything like that.” Pilgrim continued to bring in memorabilia as a way to educate his class on racism, and with every piece El-Hakim grew more intrigued (he found himself repeating this as a middle school teacher seven years later). A few months later, on a spring-break trip to Tennessee, El-Hakim bought a ceramic caricature of a black man eating watermelon, and a collection had started.

“Man, those first pieces were all figurines, sheet music, newspapers, and magazines,” he says, leaning back in his chair. “Now I can say that I have signed documents by Frederick Douglass, Malcolm X, George Washington Carver, and Rosa Parks in my collection.”

The stereotypical and abusive images and symbols of African-American history play a big role in his collection. There’s the Ku Klux Klan hood (that was purchased and donated by hip-hop artist Proof in 2005, along with local KKK Grand Dragon Robert Miles’ personal scrapbook), slave shackles, lynching postcards, “colored only” signs, and discriminatory toys. All have not been embraced.

“Some people believe that some of my artifacts are just rehashing old stereotypes,” he says, shaking his head. I’m able to easily connect old stereotypes with examples of how these attitudes rear their ugly heads in today’s culture and show how this ultimately leads us to hip-hop.”

Though El-Hakim has the youthful vigor of an aspiring rapper, he’s more of an elder statesman to Detroit hip-hop. He’s served as label head for Iron Fist Records, managed acts 5Ela, Jessica Care Moore, Proof, the Last Poets, Baatin, Versiz, and 3rd Eye Open, and consistently extends the proverbial olive branch to all local hip-hop acts. “Participating in the culture of hip-hop makes you a part of the culture of hip-hop,” El-Hakim says as he briskly thumbs through pages of his first publication, The Center of the Movement. The book is a 175-page pictorial odyssey through the history of hip-hop, with a Detroit slant.

“Here, right here,” he says as he opens the book to a photo of a green 1997 flyer that reads “5Ela at the Magic Stick. Also performing: Eminem.” He eyeballs the words on the flyer and grins as if it’s his first time seeing it. “This is when Eminem opened up for 5Ela; it was their first time sharing the stage together. Think about that — Eminem was opening up for them!”

He then turns to a 1998 Detroit’s Most Wanted album cover, an Esham 2002 concert poster, a 1985 Awesome Dre and the Hardcore Committee show flyer, and a 2005 flyer for a show in Helsinki featuring Proof and Royce Da 5’9.

El-Hakim stands up as if he’s in front of a podium.“Before this show, the last time Proof and Royce were together was in a jail cell for pulling guns on each other.”

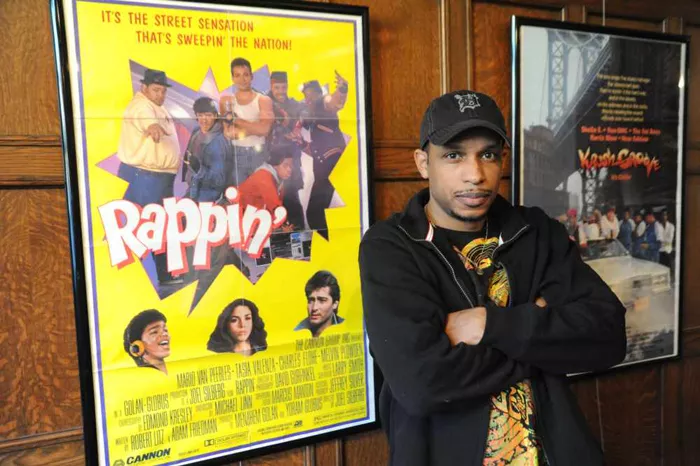

Among the 150 artifacts in The Center of the Movement, there are also several from mainstream artists and projects — a backstage pass and playlist from a Jay-Z concert, Fugees and Nas press kits, Beat Street and Krush Groove movie posters, a Public Enemy jacket, Flava Flav and MC Hammer action figures, Beastie Boys and Run DMC buttons, and autographs from Mos Def, Ice-T, Shock-G, KRS-One, Naughty By Nature, Grandmaster Flash, and Whodini. Despite the star power, El-Hakim acknowledges that the interest in Detroit hip-hop outside of Michigan is what drives him, and it’s never been greater.

“When I’m showing my collection in New York and Cali, folks always ask about Dilla, Supa Emcee, Proof, D12, or Black Milk. They’re even interested in the Kaos & Mystro and A.W.O.L. memorabilia because they understand that preceded the Eminem and Kid Rock era,” he says while pointing out a photo of Awesome Dre. “Detroit has always had a national presence; the first time I heard Awesome Dre was on Yo! MTV Raps,” he says with a laugh.

In 2012, El-Hakim resigned from teaching at the Detroit Lions Academy to pursue his Ph.D. in education and run his museum full-time. He admits he’ll miss the 13 years of working directly with the youth and wowing them with his many historical images, but his resignation was necessary for the museum to move forward.

“A young emcee was looking at my work recently and wanted to know what he could do to be a part of it. I told him he already was.”

The official debut of the Black History 101 Mobile Museum will coincide with the release of the book The Center of the Movement, on May 24, at the 5E Gallery at 4605 Cass Ave., Detroit; blackhistory101mobilemuseum.com.