Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

U.K. musician Billy Bragg is widely known for his long career in music and activism, which includes a blend of grassroots forms, such as punk rock, folk music, protest music, and heritage traditions. In addition to a recent tour with Joe Henry in support of their collaborative album, Shine a Light, Bragg has written a forthcoming book on the history of a lesser-known roots movement called skiffle. Argued by Bragg to be the oft-overlooked transition between American blues and jazz and the wildly popular rock and roll bands that fueled the British Invasion of the 1960s, skiffle was a largely subterranean culture, inhabited by jazz fanatics and purists, trying to breathe new life into the stagnating post-war U.K. music scene.

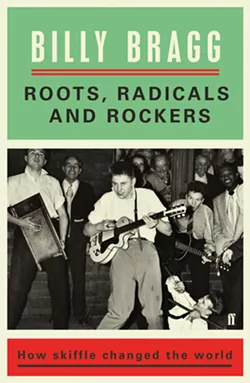

Bragg's book: Roots, Radicals & Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World (Faber & Faber, out July 11) traces skiffle down to the detail, beginning with a history of the railroad in the United States, which laid down the pathways for jazz and blues as it connected the country to its crucial musical epicenter: New Orleans. In anticipation of his U.S. book tour, which includes a stop hosted by Literati Bookstore and the Ark in Ann Arbor on Tuesday, July 18 (the event is ticketed, and includes a copy of the book), Bragg connected with Metro Times for a Skype interview on the subject of skiffle, the practice of translating complex history into exciting and approachable language, and the empowering process of viewing history from a personal, rather than an academic, perspective.

Metro Times: It struck me that your writing about music history comes from a very personal place.

Billy Bragg: It does, very much so. I was born in the year of peak skiffle, so none of this is firsthand experience, but my interest in it comes from my experience of punk rock, when I was 19. That was a very similar craze, really — the idea of do-it-yourself music, here's three chords, now form a group. In many ways, [punk rock] still shapes the things I do, in the sense that I believe you don't really need to be asked to do something or [be] given permission, you just do it. The more I read about skiffle, the more I understood about it, the more it seemed to me to be a very similar impulse.

MT: Your book kicks off with a history of the railroads in the United States, and that seems sort of counterintuitive, but the book reveals how, wherever you are when you encounter something, immediately you realize that it's connected to a whole lineage of things.

Bragg: Yeah, I mean, look at the story of "Stewball," in the book, the song that Donegan puts into the charts in 1956 — he's learned it from Lead Belly, who learned it from the Lomax recording of African-American agricultural laborers, who doubtlessly learned it from ancestors who were singing it 100 years before they were recorded in New York. The people in New York picked it up from British people — the song was sold as a broadside on the streets of London in the Georgian period — but the actual event happened in Ireland. So if you want to talk about cultural appropriation, it's difficult to know where to start with that one.

MT: And I think appropriation is often framed as this very negative thing, but there's a way that this could also be empowering, to realize that there's a great deal of global connectivity through music, even prior to our technological age.

Bragg: Particularly the appearance of the guitar in Great Britain in the mid-50s was an attempt to connect with outsiders. Before, the people who would be seen or heard playing the guitar in British culture would often be people of color — Caribbean immigrants playing calypso. Calypso came to be the identifier for post-war immigration from the West Indies, beginning in 1948. So it was an outsider instrument, and by picking up that instrument, the people doing it were siding with those outsiders.

MT: I wonder if there's also a way that, once you understand these things exist in an ongoing historical cycle, that you can also parlay it forward, to see what type of music arises, given certain economic or political or social circumstances?

Bragg: What I think you can see is that when music gets really boring, there becomes an impulse to kind of reboot the whole scene, which is often driven by people who go back to basics. The Ramones did this in America in the '70s, and Dr. Feelgood did this in the U.K., and they were both precursors of what we now think of as punk rock. That's exactly what Ken Colyer was doing, when he went to New Orleans [to learn jazz and roots music] — he was a back-to-basics purist. Now in the U.K., the interesting scene is grime. It's a type of very hard-edge rap, not mainstream at all.

MT: Another thing that I picked up on is this sense of selling out — authenticity, or the difference between appropriation in the form of homage and a sincere desire to learn, and appropriation as a form of trying to commercialize something and exploit it for profit?

Bragg: In terms of Donegan, it definitely began as homage, but what happens is that there just simply wasn't a path to making a living that didn't involve becoming a mainstream, all-around entertainer. Because he's the first, there was kind of nowhere for him to go — there wasn't a circuit for Donegan to perform in the U.K. And then, also the idea of trying to expand what you're doing. Over the years, Donegan kind of moved away from the more hardcore stuff that he'd started with, the more bluesy stuff, and moved to more mainstream stuff. His biggest was a song called "My Old Man's a Dustman," just before the Beatles came along, and that wasn't skiffle at all.

MT: I wonder if you have any feelings about being in an active conversation with this history? Bragg: That's how I want it to be, more conversational. I want to remind people that I'm not an academic — I'm a music fan and I'm a music player, trying to join the dots between some things that most of us can see. I scoured the music papers from the 1950s, and picked out the facts that I thought were pertinent, and tried to make a narrative out of them.

MT: I would rather, any day, read something by someone who is really obsessed, than something in a formal and academic tone.

Bragg: I didn't want there to be distance between the narrative and me. I wanted it to be almost first-person.

MT: Music is such a living art. You say: "Before commerce made ownership the key transactional interest of creativity, songs passed through culture by word-of-mouth and bore the fingerprints of everyone who ever sang them." So in a way, it's making this history something you can put your hands on.

Bragg: Yeah, I'm putting my hands on the history of skiffle, now. You know, it may be that people come to skiffle through my book, and then find out other things that contradict some of the things in there or add to some of the things in there. I'm trying to draw people's attention to something important that happened, and I hope that they'll be fired up about that to find out more — particularly Americans who are interested in the British Invasion, because it's a very important part of that particular narrative.

MT: So, let's assume your fondest hope is realized, and people want to know more? What's an album I should get or a book I should read to learn more about skiffle?

Bragg: Well, weirdly, there are no real skiffle albums. Most of it happened on 10-inch 78 singles — apart from Donegan, who is the exception who proves the rule — but you can still find it dotted around on Spotify. So you should use the titles in the book to listen to stuff on Spotify, Colyer and his Jazzmen, and to the skiffle artists as well, and see if you can hear just an echo of the shockwave that went around Britain in the 1950s. It's something that I think Americans would be interested to know about.

Literati Bookstore presents musician Billy Bragg at the Ark in Ann Arbor on Tuesday, July 18, to talk about his new book Roots, Radicals & Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World (Faber & Faber). Bragg will read portions from the book, speak on the importance of skiffle in U.K. musical evolution, and sign books. Doors: 6:30 p.m.; Show starts: 7 p.m. Tickets are $35 and include a hardcover copy of the book.