A conversation with Black Rebel Motorcycle Club's Robert Levon Been

Creature comforts

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

The first time Black Rebel Motorcycle Club reared their unwashed heads was around the turn of the century. "I gave my soul to a new religion," Peter Hayes screams against frayed and fuzzy guitars of their breakout hit, asking, "Whatever happened to our rock 'n' roll?"

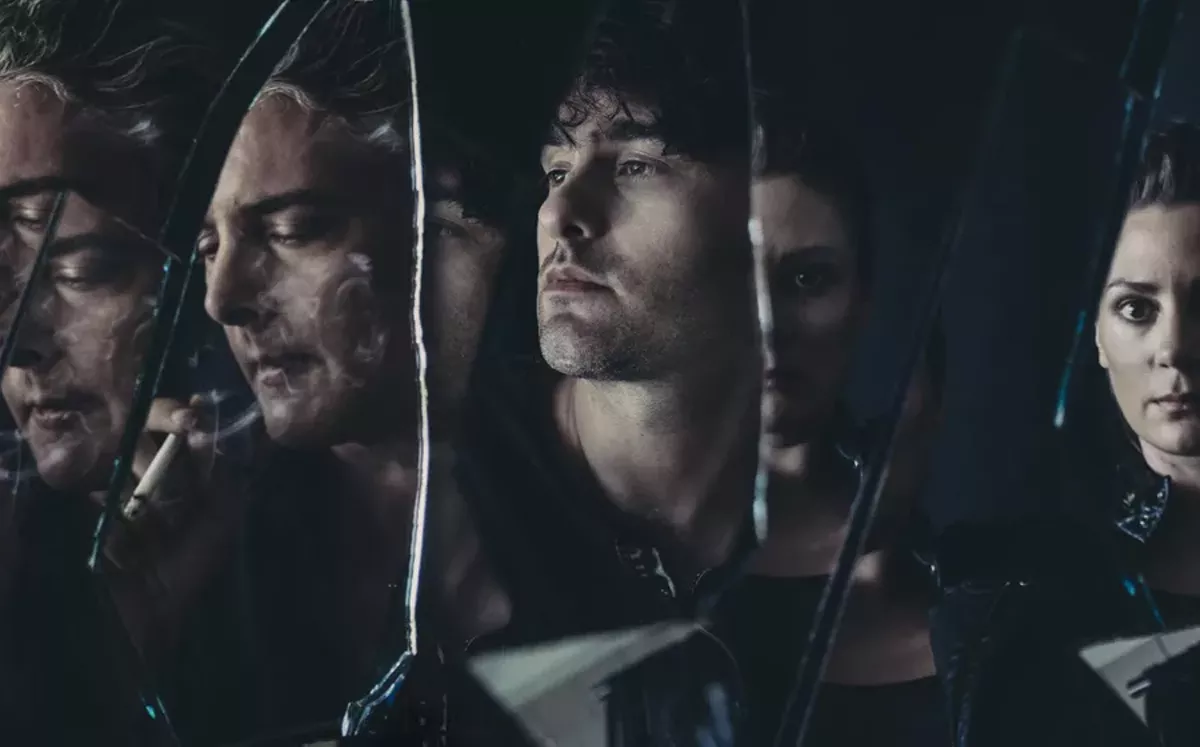

In terms of rebellion, they are not the first, nor will they be the last, to exercise defiance with scuzzy guitar licks, foot-pounding drums, or an all-black leather uniform. What BRMC's Robert Levon Been, Peter Hayes, and Leah Shapiro prove is that rebellion has little to do with shock and awe and everything to do with the sanctity of rock 'n' roll — even if it means staggering down a different path to a frequently visited destination. What BRMC offers is a provocation by virtue of restraint — leaving plenty of room to breathe and bleed.

This is true of BRMC's latest record, Wrong Creatures. By no means is it a departure from the frayed and formulaic BRMC default. Instead, Wrong Creatures is a graceful rumination peppered with chaos and it perhaps answers the question better than any progressive leap into unexplored territory could — what happened to our rock 'n' roll?

Well, it never really left. After 20 years and eight albums, BRMC's Robert Levon Been has a confession to make: "It never gets easier."

"Maybe it's just the pressure we put on ourselves to dig as deep as we can to get to something worth saying, something worth bringing to people," he says. "Each album we kind of give a little less of a fuck what happens. Each album we shed another layer of skin which is hard. It's like we're trying to move mountains that don't exist."

The mountains on Wrong Creatures may not be an impossible climb, but represent a defining moment. The five years between 2013's Spector at the Feast and Creatures was riddled with uncertainty as drummer Leah Shapiro underwent brain surgery after being diagnosed with Chiari malformations — a rare condition that challenged balance, coordination, and offered grim, life-altering symptoms.

"You experience things you never expect to," Been says of Leah's recovery. "We're kind of proud people to a fault, so we didn't want to ask for any help. Then a couple fans started fundraising for her and I didn't know what to do with that level of kindness. I had never experienced that before," he says. "It kind of shakes me from my tree of pessimism that I like to climb and hide in."

BRMC has often been criticized and praised for their ability to skirt the line of ambiguity. Lyrically, they've been known to paint in broad strokes. Love songs are synonymous with potential protest anthems and declarations of grit, gore, and recklessness could just as easily be interpreted as a search for salvation. Even when politics and America's many blunders serve fair fodder for rock 'n' roll commentary, when it came to Wrong Creatures, Been preferred to let the light in by leaving the door open.

"It's not so much the man or the government or the propaganda — it's the sense that we're all different and so disconnected, and polarized," he says. "I think that's what sells newspapers and it creates a sense of tribalism. I don't trust it. I have tried to find my way in that. You just have to take the names and places and addresses and street corners out of the song to kind of open the song up as much as you can while also making it sting. That's the more interesting song to write."

"Little Thing Gone Wild" is inarguably the most BRMC moment on the album — with its shrieking, shredding, searing animalistic urges, the song reminds us that the band has not lost its grip on rattling rock bravado as Hayes growls, "I wanna shake the ground till I am done reaping/ Lord do you hear me loud; Unto my soul speaketh/ Oh won't you let me out, you got the wrong creature."

"A lot of the songs on the album felt like they had something to do with feeling locked inside yourself and scratching or clawing your way out of it," Been says. "Then again, Wrong Creatures, just sounded cool."

Been knows a thing or two about "cool," a word he can't say without laughing. He grew up on the road. His father, the late Michael Been, fronted cult-status rockers the Call. "It seems like pretty normal because I have nothing to compare it to," he says. "It's not an MTV music video or a magazine cover. For me, my memory of music is very different than other people's. It's more like a blue-collar job. You always get people who can only relate to music in the terms of big success or that kind of glory and fame that comes with it. The music is always better when you can shut that out, let it be what it is."

Time, both past and pending, seems to distress Been. He stammers when asked about legacy and openly grapples with the band's rightful place between the shadows and the spotlight. He is overwhelmed by compliments or any gesture of fandom, and when it comes to the future, he can't look that far ahead. It is this marriage of humility and angst that keeps the band relevant, and maybe that's why Black Rebel Motorcycle Club still feels as rebellious as they did 20 years ago. They don't try, they just are.

"I kind of just go back and forth between being really resentful that we never got our day in the sun," Been says. "At the same time, knowing that if we ever did have arena-level, number one album success we would have probably imploded and it would have been the last of us. I know us as people, we couldn't have handled that."

"It's a blessed curse that keeps us right in between threading the needle of success and existence."

Black Rebel Motorcycle Club will play on Wednesday, Feb. 7 with special guests Night Beats at the Majestic Theatre; 4140 Woodward Ave., Detroit; 313-833-9700; majesticdetroit.com; Doors open at 7 p.m.; Tickets are $25-$30.