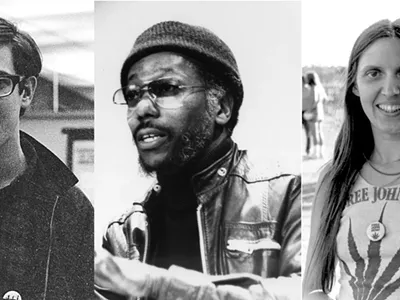

This perspective on the events of the summer of 1967 comes from a few Metro Times fellow travelers in the form of John and Leni Sinclair, and Fifth Estate staffers Harvey Ovshinsky, Peter Werbe, and Frank Joyce. We also sought out John’s old pal Pun Plamondon, as well as author, activist, and longtime MT editorial adviser Herb Boyd, and scholar, journalist, and Hush House co-founder Charles Simmons. Additionally, we talked with Reggie Carter to represent the teenage black radical contingent of the day.

In our interviews, we heard the words “rebellion,” “riot,” and even “ri-bellion” to describe what happened 50 years ago.

Reggie Carter: I think it's important to understand and make that distinction between it being a “riot” and it being a “civil disturbance” or an “insurrection.” Because words matter, and it really doesn't get at the heart of the matter if you're not accurate in the labels you use to describe it.

Pun Plamondon: I mistakenly called it the riot in my book but i now wish I had used the word “rebellion.”

Frank Joyce: I very much call it a rebellion. You know, a riot is something that college kids do in Daytona Beach. This was not that. This was political. And I said it at the time, I've said it ever since, I still say it: It was a rebellion.

Harvey Ovshinsky: The “ri-bellion” ― that's what I call it now. Everybody's been tripping over themselves on what to call it. So I've just recently been calling it the ri-bellion, because it was both. [laughs]

Frank Joyce: So many white people are so wedded to calling it a riot as opposed to a rebellion or an uprising or an insurrection. The history of criminalizing most behavior by blacks goes back to the origins of white supremacy itself. Moral supremacy by fiat force and power is one of white supremacy's core components. As we know from whites destroying property by throwing tea in Boston Harbor, rebellion is in the eye of the beholder. Especially in a nation whose founding mythology honors insurrection, the word rebellion has serious legitimacy. “Riot,” on the other hand, conveys criminality. Hence most media and many whites prefer “riot.” Perhaps more importantly, using the term “riot” perpetuates white denial that blacks would have anything to rebel about.

Peter Werbe: A rebellion is usually launched. It has programmatic content and goals. I don't agree with Frank. I don't think it diminishes it to call it a riot. In fact, in some ways, it seems more honest and genuine, as opposed to a bunch of leftists saying, “Let's get the masses riled up enough so they will carry out the program.” Because if you're going programmatic, how many people are involved with that? In some ways, riots are more democratic. [laughs]

Charles Simmons: Was this a riot or a rebellion? There's elements of both, but the idea of having a plan … the group did not have a plan. It was an outburst of rage, but it wasn't something that was organized, like when you talk about revolt being organized.

Herb Boyd: So often when you hear “riot” usually you put “race” in front of it: It's usually a “race riot” as opposed to a “race rebellion.” The race element was only coming in the sense that you had the white riflemen in there shooting down black people. And it was not so much white residents against black residents. Unless they were racing to throw a brick through a store window. [laughs] There was very little conflict on that level, as I remember. … These people were struggling, fighting back against a certain kind of systemic oppression that they were feeling. It had less to do with antagonism among residents as much as a kind of a standoff against the status quo, the state, the municipality, and the repressive aspects, including the police.

John Sinclair: It wasn't a race riot in any way. If it had to be called a riot, it was an anti-police riot. It was touched off by police misbehavior.

Some of our interviewees reacted strongly to the word “counterculture” – and even “hippie.”

Leni Sinclair: I hate that term: “counterculture.” That's a term that was imposed upon us, same as the word “hippies.” We didn't call ourselves hippies. To me, the “counterculture” wasn't against anything. I think of it more as an extension of the culture or a mind-expanding of the culture that was already there.

Peter Werbe: Counterculture? Well, there has to be terminology to describe events or developments in the culture, and this one that was developed that came out of the bohemian, beatnik era and into the New Left and the hippies, I think it was adequate: It was counter to the existing culture. It was subversive, in that it called into question all the mores of our stultified, stiff, uptight, all-white culture.