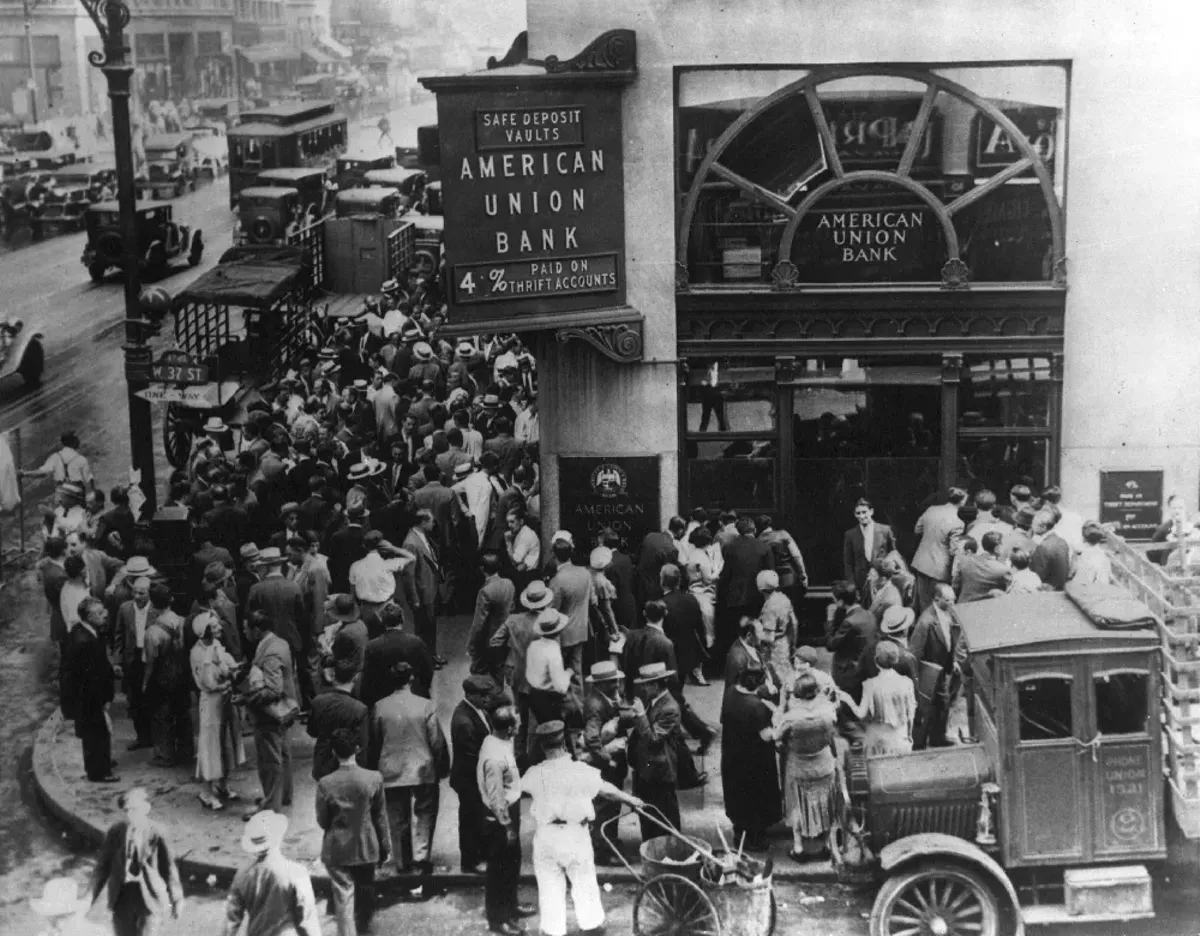

In 1933, at the height of the Great Depression — a year after the U.S. economy contracted by 10 percent and just before FDR's New Deal took effect — American unemployment hit an almost unimaginable 24.9 percent, a record that stands 87 years later.

It's time to imagine it again.

In the week that ended on April 11, according to the Department of Labor, more than 5.2 million people filed initial jobless claims — more jobs lost in one week than the economy gained in all of 2017 and 2018 combined. This was, stunningly enough, an improvement over the two weeks prior, when more than 6.6 million and nearly 6.9 million filed claims. All told, in the four weeks after President Trump (finally) declared a state of emergency, the U.S. economy lost at least 22 million jobs, about the same number it gained since 2010.

The Great Lockdown, in other words, destroyed in a month what the recovery from the Great Recession built in a decade.

Economists say unemployment is probably hovering around 20 percent or higher. In Michigan, more than one in five workers have already applied for unemployment. The same goes for Florida. In North Carolina, about 14 percent have. In New York, at least a million people have filed for benefits despite a problematic and overloaded system. More than 15 percent of Americans could fall into poverty this year, researchers say, many of them Black and Hispanic.

This is going to be ugly — and we're only at the beginning.

The annualized second-quarter GDP contraction could hit 30 percent, three times what it was following the financial collapse in 2008, as commerce has frozen in place for a month or six weeks or longer. And the optimistic scenario foresees us ending the year with unemployment at about 10 percent and GDP recovering to about a 5 percent loss.

But that depends on us getting the new few weeks right.

Before moving on, let's pause to acknowledge the scale of the human tragedy: As of Friday morning, the United States had 671,425 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 33,286 deaths from the disease. That's about 50 percent more deaths and 360 percent more diagnoses than the closest countries, Italy and Spain, respectively. While the U.S. is much larger — more than five and six times their respective populations — the Trump administration also had a longer window of time in which to prepare for the pandemic, and it failed to do so.

Writing in The New York Times, epidemiologists Britta L. Jewell and Nicholas P. Jewell say that had President Trump acted sooner — issuing social distancing guidelines on March 2 instead of March 16 — "an estimated 90 percent of the cumulative deaths in the United States from COVID-19, at least from the first wave of the epidemic, might have been prevented." Even issuing those guidelines on March 9 would've meant "a 60 percent reduction in deaths."

At the time, however, the president was more interested in propping up the stock market than acknowledging the crisis. On March 6 — a week after promising that cases in the U.S. would soon be "close to zero," the virus will "disappear," and "everything is under control" — Trump insisted that "anyone who wants a [coronavirus] test can get one," a statement that was not true then and is not true now. On March 10, Trump said, "Just stay calm. It will go away."

The administration's dithering also did enormous damage to the economy. An analysis by Robert J. Shapiro — a senior fellow at Georgetown University's McDonough School of Business who served in the Clinton Administration's Commerce Department — comparing the U.S. to Germany and South Korea argues that at least 40 percent of the carnage can be traced back to Trump's inaction.

Which is to say, there's both blood and misery on Trump's hands.

In late March, Congress passed a $2.2 trillion rescue package to keep businesses afloat and prevent the economy from spiraling. Its shortcomings are already obvious.

The $349 billion Paycheck Protection Program, designed to subsidize employers not to lay off employees, ran out of money within two weeks. The Economic Injury Disaster Loan program has almost run dry. Even the $1,200 stimulus payments haven't gone out smoothly: Paper checks were delayed so the Treasury Department could put Trump's name on them, and millions of taxpayers didn't get their funds direct-deposited because they'd used third-party filing services like TurboTax.

From the outset, the PPP has been a bureaucratic train wreck. The administration was rewriting the rules until just before the program launched, leaving lenders in the dark. The second it did launch, systems were overloaded with demand, and small businesses without established relationships to connected banks couldn't even put through applications.

Once applications went through, rural and red states, some of which were barely touched by the coronavirus, appear to have gotten more PPP help than hard-hit blue states. In the first 10 days of the program, according to a Bloomberg News analysis, Nebraska got enough money to cover 75 percent of its payrolls, and Wisconsin received 63 percent. But California and New York? Just 24 percent and 25 percent, respectively. Michigan and Florida: 39 percent. North Carolina: 38 percent.

And because of a loophole allowing giant restaurant and hotel chains to cash in on money meant for struggling small businesses, the Florida-based Ruth's Chris Steak House chain scored $20 million from the PPP pot, while the Potbelly Sandwich Shop chain got $10 million.

The administration now says it needs $250 billion more. Congressional Democrats want to tie to help for devastated states and cities, hospitals, and people on food stamps who are likely to otherwise be left holding the bag. Republicans have refused. The longer the stalemate, the more businesses will go under, and many of them won't get up again.

Even for those who get the money — and who hold on to their employees until the end of June to make the PPP loans forgivable — the funds are only designed to hold them over for two months. So if the economy's not roaring back by summer, another Depression-like round of massive layoffs is coming.

That's why Trump is hellbent on reopening the economy even when public health officials are wary. On Thursday night, the White House released guidelines for reopening the country. Written by doctors, it's a cautious document, certainly more cautious than the president, who days earlier was insisting (absurdly) that he had "total" authority to force states to lift stay-at-home orders.

Trump was more cautious in another way, too. While he encouraged governors to open sooner than later, and he preferred they did so before May 1, he said it was their call. The deferential announcement, it seems, was timed to get ahead of own-the-libs govs in Texas, Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi who were going to reopen anyway, so Trump wouldn't look feckless. Trump being Trump, however, this move is also a rather obvious ploy to shift responsibility: If a state's economy is in the toilet, Trump can blame the governor for waiting too long; if a state has a deadly coronavirus outbreak, Trump can blame the governor for opening too soon; if a second wave grips the country this fall, Trump has partners with whom to share culpability.

This is part of a pattern of diversion and blame-shifting, of course. To blame China for the novel coronavirus, Trump and his advisers are pushing an evidence-free conspiracy theory that it emerged from a research lab in Wuhan, where it might have been engineered; scientists say the virus's genomes make this highly unlikely. Trump also cut off funding for the World Health Organization — amid a worldwide pandemic, no less — accusing the WHO of furthering Chinese propaganda and causing "so much death." (In late January, Trump praised the Chinese for "their efforts and transparency.")

It's China's fault. It's the WHO's fault. It's American governors' fault. But Trump? "I don't take responsibility at all."

To reopen responsibly, the U.S. needs a testing-and-tracing system like South Korea implemented. To make that happen, the director of the Harvard Global Health Institute says we need to test 500,000 people a day — 350,000 more tests per day than we're doing now. (That's a lowball: A white paper from the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics puts the number of daily tests in the millions.) Without being able to quickly identify and quarantine the infected, social-distancing measures have to stay in place to prevent an outbreak. Otherwise, everything we've endured over the last six weeks has been for naught.

But states don't have the resources to do that kind of testing right now; to get there, they'll need the feds' help.

"The biggest problem we have right now is testing capacity," North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper said on MSNBC Thursday. "What we need from the federal government right now is help on that testing capacity and with supplies and with personal protective equipment."

The White House, however, has told them that testing is their responsibility.

"The President doesn't want to believe that testing is a problem," Cooper continued. "And it is a problem, particularly if we want to get the country going again."

The coronavirus has made life difficult for independent media. You can help keep Informed Dissent viable by contributing to patreon.com/jeffreycbillman.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.