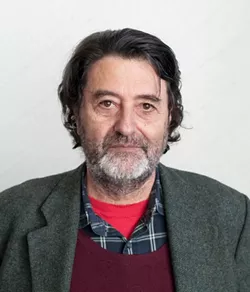

Chilean-born Camilo Jose Vergara is the country's premier photographic chronicler of the American inner city.

He started out in New York City in the 1970s and 1980s, carefully re-photographing urban landscapes from the same position, creating a visual record of poor neighborhoods as buildings fell victim to disinvestment, arson, and demolition. Long before the term "ruin porn" was coined — and decades before Google Street View — Vergara was systematically documenting the flagging fortunes of U.S. cities.

"You'd carry a little slide with you," Vergara tells us from his home in New York City, describing how he'd return to locations and shoot the same view years later. "Of course, I wasn't redoing every single shot, but before going back, I'd look at what I had. ... And you also had to do remember how you shot from different places, whether from the ground, the roof of a car, or the roof of a building"

Vergara's findings were compiled in the 1995 book The New American Ghetto, which burned through three printings, and a popular photographic exhibit of the same name. He began to be regarded as a sort of modern-day Jacob Riis, showing how the other half lives — with the difference that the ghettos in the days of 19th century Riis were crowded and dense, while Vergara's photos laid bare the 20th century's spatial deconcentration of the poor.

Vergara went on to win a MacArthur Genius Grant, authoring several books about his photographic preoccupations, inner city Christianity and vernacular art, among them. While the places he photographed at their nadir in New York are now glittering with wealth, his efforts to document the Rust Belt still showcase our region's signature decline.

Vergara, who has been visiting Detroit every year since 1991, has finally compiled his photographs of Detroit into a new book released last month, Detroit Is No Dry Bones — a long, fond look at the city Vergara finds, in its intact opulence and even in its decay, rich with beautiful imagery. His book from a dozen years ago, How the Other Half Worships, lingered lovingly over Detroit's profusion of storefront churches.

These days, with Detroit basking in media attention, the timing must have seemed right for a book devoted to the Motor City.

"Attention is a form of capital, and Detroit has gotten a tremendous amount of attention from the media," Vergara says. "And of course, Detroit has been the epitome of depopulation."

Often guided by a few locals in the know, Vergara has spent more than 25 years putting together a treasure trove of photos of Detroit, some showing how buildings have evolved over time. "I have little sequences," he says. "I can't put everything in the book, so I often put in the first and the last one."

It also gives him a perspective quite different from the national journalists who paratroop into select neighborhoods, see a restaurant crowded with people, and declare the city as rehabilitated.

Referring to a recent piece by Michael Kimmelman in The New York Times, Vergara says with a laugh, "In the article, he goes to that block of Livernois that everybody goes to, to the restaurant that everybody goes to, and he tells everybody it's full of people, you know, so Detroit's coming back. ... Because you figure if something was getting better, you'd think you would notice it in what used to be called the worst places."

It is those places that arts correspondents from The New York Times don't go that Vergara knows best and loves most. It's where he has met solemn pastors, longtime residents, and even by-the-job muralists like Bird, profiled in a recent Metro Times article.

For all the disinvestment, though, Vergara says, "That's a very vibrant side of these neighborhoods, that's very much being missed."

While Vergara's book opens with pictures of Detroit's skyscrapers and civic treasures, it doesn't take long for him to get to the things he loves best: vernacular art, and the way the city's shifting fortunes are visually recorded.

"Basically, what happens is, there are thousands and thousands of establishments — storefront churches, liquor stores, all that stuff — that feel they have to have a mural because they're in the neighborhood. Then there are all these sign-painters that go down the street. Here you have a place that would sell new cars, but new cars weren't sold in Detroit anymore so it would turn into a mechanic shop, and then there were no mechanic's shops so it turns into a car wash, so all that downward mobility was recorded in signs, by people who lived precarious lives. Some of them were homeless. Sometimes they would be given whatever paint the shop had there already. And the owner of the shop would say, 'I want a picture of myself,' or 'I want the Bible.' So then they had to do it."

"All of that are elements of a lifestyle of design," Vergara says. "I mean this is what The New York Times chronicles regularly — but for rich people. But I don't want it to be ignored.

"The story is not very complicated. It's just that tens of millions of people live in ghettos in the country, and we all know examples of movie actors that came out of there, athletes, musicians, but you know what you don't have? None of the famous black artists, and I mean visual artists or architects, come from that area. And then I remember all these years of going to storefront churches and looking and seeing all the stuff that people put up there. You know, going into the party stores, barbershops, getting a haircut, and seeing a completely different sense of order, design, signage, and also seeing that nobody was preserving that stuff."

Vergara sees a wealth of vernacular art to be shared and extolled, and you can sense his despair as it is overlooked by the very people who choose to become the city's newest residents.

"That's why I want to make them visible. And that's why the book, by the way, ends with one of those reliefs by Corrado Parducci, where you see money being carried to a vault and all these white men with suits. That as well as the symbols of Detroit at its highest point, they are visual elements that define the Detroit that's coming out. And then all of this is as if it didn't happen. It's sent into oblivion.

"And it's not just being erased, it's being replaced. You have a population that stayed there that is close to 600,000 people and that population when it comes to internet use, self-promotion, being assertive, it's lost most of the people who would be assertive. They've moved out. You know, so what they have left there are people who don't have the means to connect to this modern society, this global economy, the way your average gentrifier in Detroit does. And that's why I think it's very important, at least, to be aware of that. I don't know what you can do — but I can't imagine the future. But it's important that there is an awareness of things like this."

Camilo Jose Vergara is scheduled give two artist's talks this week. At 7 p.m. Jan. 25, he'll appear at Literati Bookstore, 124 E. Washington St., Ann Arbor; 734-585-5567; literatibookstore.com. At 7 p.m. Jan. 26, he'll appear at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, 4454 Woodward Ave., Detroit; 313-832-6622; mocadetroit.org.