Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Boiling Shakespeare’s play down to its most elemental parts, Joel Cohen’s Tragedy of Macbeth is an exercise in lavish, purposeful minimalism executed from a place of experience and taste. With an air of efficiency lending some sense of opacity (as is common in many collaborations with his brother Ethan, who’s absent here), the project doesn’t bear many obvious markers of the personal, even as it stars his wife (Frances McDormand, capping off a refreshingly good year). But with its themes of fate, ironically meted retributive justice, pride, and scrabbling, dubious ambition, it resonates across his shared body of work and more widely nonetheless.

Much of what Coen’s about here seems to be an exercise in cooking-down, working with cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel (Amélie, The French Dispatch) and production designer Stefan Dechant to give Tragedy a honed, intensely deliberate look. Centering his compositions symmetrically as in his signature work with Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Delbonnel’s subject matter here is far less sweet, spotlighting barely-furnished castle halls and chambers opposite outland shacks which seem to float on seas of grass and fog. Channeling Orson Welles’ scrappier, leaner, and, as a matter of both vision and necessity, more suggestive black-and-white adaptation, Coen’s aesthetic feels sharp, orderly, and compressed here, lacking any trace of shagginess and avoiding the hubris of its cast in its direction. But in this largely familiar mounting there’s still some tinkering done: one(?) figure (played with a reckless sense of invention by Kathryn Hunter) seems to take the place of three witches (it’s complicated), rolling sound-stage sets create a barren landscape whose contours shift with the mind of its inhabitants, and a procession of splendid performances and smart flourishes casting lend a variegated sense of ingenuity. Overall, there’s a diffuse air of hazy, dream-like subjectivity or surreality that complicates the production’s tidy air.

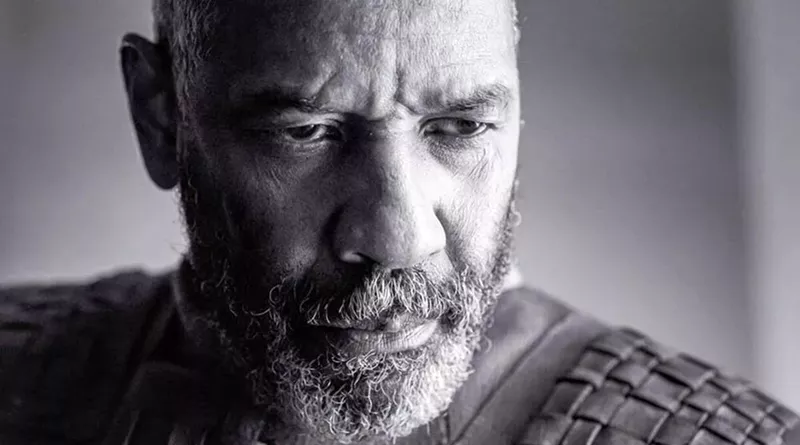

Chief among them — unlike in most Macbeth re-stagings, in which the Lady steals the show — is Denzel Washington’s rendition of the title character, with which he seizes control of the film with less apparent effort or agony than his character takes the throne. Delivering his lines in the source text’s precise verse, he manages to grant them an offhand, freely modern quality that makes them all the more beguiling. Prone to a kind of self-contented, low-boil vanity more than any roaring, outward-facing sort of ambition, Washington’s Macbeth acts out violence with an air of largely muted grievance at the goading of his Lady. Outbursts at courtiers, finely rhythmicized soliloquies, and manic, late-stage visions (or encounters?) provide a range of surfaces for him to break against as an actor. But Washington, mutable though he is here, is inevitably himself: sometimes distractingly but always beautifully so. Coen’s aesthetic work here on some level seems to merely make way for him, as the text feels more truly to belong (if not too loudly or as a matter of effortful force) to Washington over anyone but Shakespeare himself.

Washington’s ability to so easily take over the film, though, speaks nearly as much to his own skill and presence as to the film’s erosion of obstacles or distractions that might fight him for the spotlight. For Tragedy is relentlessly direct (though to be fair, the play — to me, at least — has always seemed like one of Shakespeare’s juiciest, plainest, and least-adorned). Coen and Delbonnel frame dialogue scenes in stark shot-reverse shot sequences before well-shaded walls with high-angle architectural shots cut in. The latter work can feel a bit like seasoning for the former: a measured doling-out of some needed variety rather than personal expression through form. But if what Cohen’s doing is at once applying a finely wrought if slightly rote style as a means of getting out of the way, there are many worse ways to do so — and it stands to flatter the elemental qualities of the text as well as the film’s troupe of able performers.

As a companion to Washington here, McDormand’s work strikes a contrast. Performing in modes both rangier and more overtly chewy, she operates in a more familiar theatrical mode. Delivering Shakespeare’s lines with a clearer sense of relish, her quick-flowing consonants fall with an air of crisp, informed decision, giving space to a rushing stream of emotional (and rhetorical) tones in her private moments of intimacy and coercion. To the film’s small onscreen public, she seethes with a barely-veiled readiness to strike, offering cordial gestures of hospitality with clipped, eager lines given out only to be countered from a restless, almost frantically busy face. Compared to Washington, her Lady is more straightforward beneath her air of insistent connivance. A being of exceptionally pure ambition, volatile discontent, and self-regard, her guilt by the story’s end (“Out, damn spot,” etc.) comes off on a psychological level as something of a surprise. Washington, on the other hand, seems a far less reliable instrument of her aims, rocking quietly between his own conflicting doubts, desires, and designs.

Such figures as his are what the Coens’ work has long been made of. Their penchant for ill-fated acts of violence, retributive and karmic logic, and buffoonish strivers all certainly have a home here. But while the events of Tragedy of course go awry, there’s not too many traces here beyond Washington and Hunter’s performances of bemusement, of comic irony, or of subversion that make it to the screen. Such features are amply present, by contrast, in the Coens’ other recent work. Take Hail Caesar! or The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, which skewed more iterative of old modes and responsive to cultural and political history than they were concerned about offering something self-styled or forcedly “authored.” But these works were imprinted anyway with the Brothers’ stamp, being slyly reclamatory, and subversive in their trademark (and increasingly opaque to many) polyvalent fashion. I’ve little doubt there are forms of subversion and personalization I’m missing in Tragedy, but Cohen’s solo effort here feels more artisanally than artistically shaped anyway. The result, while distinctly pleasurable and often striking, can feel like something of an exercise, a brilliant director and his collaborators presenting a cut-and-polished version of a beloved gem of a text: something I’d register more as a description than as complaint.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Reddit.