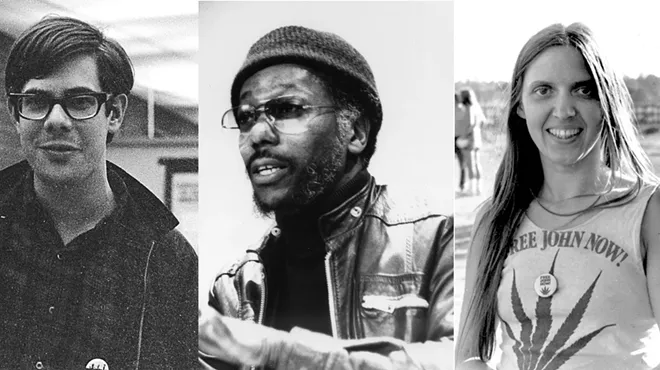

This perspective on the events of the summer of 1967 comes from a few Metro Times fellow travelers in the form of John and Leni Sinclair, and Fifth Estate staffers Harvey Ovshinsky, Peter Werbe, and Frank Joyce. We also sought out John’s old pal Pun Plamondon, as well as author, activist, and longtime MT editorial adviser Herb Boyd, and scholar, journalist, and Hush House co-founder Charles Simmons. Additionally, we talked with Reggie Carter to represent the teenage black radical contingent of the day. Between all of these folks, we hoped to gain some insights into what political radicals and the “hippie counterculture” — a phrase many of them privately grimace at — have to say about that time.

In our interviews, we heard the words “rebellion,” “riot,” and even “ri-bellion” to describe what happened 50 years ago, but the “rebellion” in the title of this feature is not a reference to the incident. It’s rather an allusion to the subversive spirit of those who were generous enough with their time for this entertaining oral history. Find more detailed narratives from this uncommon group of freethinking Detroiters here.

Charles Simmons: Why did '67 occur? What led up to that? When I start thinking about it, well, the coming of Columbus was the beginning of it. There's an unbroken continuity of struggles against injustice all the way back to that period. [laughs]

Harvey Ovshinsky: It started when we took Belle Isle from the Indians. It's inherent. Detroit was an American city. It has American problems. And slavery is the curse of America. Until we work it out, it's just going to bite us all in the ass.

Charles Simmons: It's like Langston Hughes said: "What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? ... Or does it explode?"

Harvey Ovshinsky: It was incremental. It was both big and incremental, but mainly it was incremental. I mean, how much shit can you put up with before ... You put a pot of water on the burner, and if you don't lower that heat it's going to boil over. And that's what happened.

Charles Simmons: There were so many issues. Economic issues: At that moment, you've got the speed-up in the factories with the new technology. There was also the Vietnam War. And we're seeing this war on television, and then we've got the soldiers going back and forth, and they're sharing their experiences about racism in the military, as well as the racism at home. Discrimination: We didn't have any black foremen or any black people working in the offices. And then you've got the housing stuff. We were paying high rents. And, earlier in the decade, the City Council had actually voted to support segregated housing.

Peter Werbe: Just 24 years earlier, there had been this horrible race riot in Detroit, and so the contradictions of race were still really throbbing. You add to that the beginning of the disintegration of the economic structure and this brutal, corrupt police force, and it's a prescription for what we saw.

Herb Boyd: Relations between police and black Detroiters have a long and troubled history.

Frank Joyce: Enough can't be said about the politics of the white police as an occupying force in the city of Detroit. This notion that it was the job of the police to sort of keep control of the black community in general, and black males in particular, was a very entrenched feature of life at the time.

Harvey Ovshinsky: There were two policings of Detroit citizens. If you were black, you got one style of policing, and if you were white, you got another style. If you were white, you didn't worry, you respected the police. If you were black, it was another story.

Peter Werbe: We always got treated very badly by the Detroit cops. Even when I was 13 and 14 years old, these cops regularly would stop us and steal our cigarettes. They'd say: "Got my pack today, Pete?"

Frank Joyce: Joining the civil rights movement was eye-opening in many ways, including being with black people when they had police encounters, which were, of course, nothing like anything I'd ever experienced, in terms of the hostility, the fear.

Peter Werbe: We began running into cops when we were with the civil rights movement. When they attacked the group, they didn't discriminate then.

John Sinclair: I don't know if they had 10 percent black officers. I'll bet it was less. Certainly in the command structure, there might have been two blacks.

Reggie Carter: The police department was overwhelmingly white, and even the few blacks that they had on the police force had a reputation for viciously assaulting blacks.

John Sinclair: They knew they were wrong, too, in terms of policing the populace in a rough, and rude, and illegal manner. So I guess they expected something to happen. They had to. They were probably shocked that it took so long. [laughs]

Some of the roughest, most illegal policing came from elite units known as "the Big Four."

Frank Joyce: The Big Four were beefy white guys who rode around in Chrysler 300s. They were correctly reputed to have in the trunks of their cars an arsenal of shotguns and other weaponry beyond the pistol and nightstick of the average beat cop.

Peter Werbe: They were just the meanest, ugliest, stupidest guys you'd ever run into.

John Sinclair: The Big Four could do whatever they wanted. They were patrolling the black community to make it safe for the white merchants, and landlords, and city government, and white people in the suburbs.

Charles Simmons: I knew of the Big Four since childhood. And I witnessed them beating up people, young teenage boys. Young black guys would stand out in front of the pool halls. Standing outside, in the black community, is a cultural thing. But the police would threaten you and curse at you and say, "If you don't give me that corner, I'm going to kick your ass when I come back, motherfucker." That was their style. The composition of the Big Four was one uniformed white dude and three big brutes in suits, and they had baseball bats, billy clubs, brass knuckles, all sorts of torture stuff, and they would whip your ass. And God forbid they should take you to 1300 [Beaubien St., Detroit Police headquarters]. You'd just get stomped, and you were lucky to leave there alive.

‘He was throwing a bottle because of slave ships and chains and whips and what have you that coalesced right in that moment.’

tweet this

Herb Boyd: You knew when the Big Four was cruising around the neighborhood, really harassing and intimidating people, saying, "You're kind of dark over here, gang. You better get away from here." It was like a continuation of the plantation experience, you know — unlawful assembly: too many black people in one place. We may be plotting, scheming to do something. So we were always wary of that growing up, even in our little doo-wop sessions under the lamplight in the North End. Because we knew: They come through, they'll hit you upside the head if you disobey.

Harvey Ovshinsky: We had been reporting on the relationship between the police and the black community for a while. The troubles that were brewing were not a surprise to us.

John Sinclair: They just harassed you at all times. And the thing about hippies was, like black people, you could see them. You could tell them by their long hair, different clothes, headbands, so we stood out against the landscape, and that was all they needed for "probable cause," you know? In our neighborhood around Wayne State, you couldn't walk from one side of the expressway to the other without getting stopped. And they'd go through your pockets. "He's gotta have some weed in his pocket." And usually you did.

Leni Sinclair: They would stop and frisk anybody they didn't like. They called us names, like "longhairs." But we just kept on doing what we were doing. The only thing that they could hold against us — and did us in eventually — was the marijuana laws. I mean, making poetry and music were not against the law. But smoking a joint is. And it was so much against the law that they used that to bust John three different times.

Against the backdrop of repressive policing, Detroit was a fermenting hotbed of liberation groups. Far from dampening the expectations of inner-city residents, the unfair conditions seemed to radicalize people.

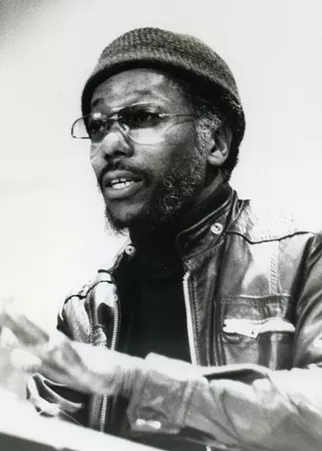

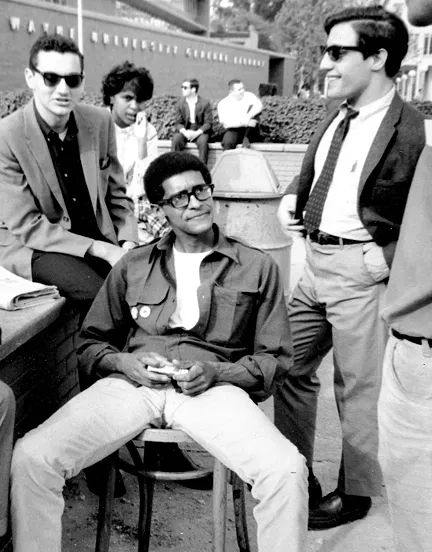

Reggie Carter: In 1967, I'd had some exposure already to radical politics. I had an older brother at the time who was involved, and I was heavily influenced by him. Detroit, primarily because of the Great Migration, was a center for social movements. It had [the] Nation of Islam, the Republic of New Afrika, black Christian nationalism with Albert Cleage, the All-African People's Union, Grace and Jimmy Boggs, Dan Aldridge, what emerged as the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement, the Pan-African Congress. Ed Vaughn's bookstore on Dexter was a hive of activity, where anybody with a social conscience came through at one point or another.

Charles Simmons: There was something wrong with the economic and political system that had to be changed. Organizations like the Black Panther Party, Uhuru, and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and some of the SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] people, the activist youth of the 1960s, raised some fundamental questions about the system that our elders in the civil rights organizations did not address. NAACP and CORE — their position was that desegregation was the solution, period. And after that, we'll live happily ever after. But they couldn't restrain the young people. In the '50s and '60s, the youth didn't want to hear anything about "go slow." Martin Luther King appealed more to the older people and the Southerners. But Malcolm X appealed more to the young men in the North.

Herb Boyd: We realized we could go ahead and flex our muscles politically and otherwise. We were empowered and emboldened, I think, to a great degree. And of course it was happening internationally too. We were being fed and energized globally because of the winds of change that blew across Europe, Asia, South America, and, of course, the African continent, and many of us began to connect with revolutionary movements across the globe. Those were very powerful symbols of change and self-determination, and many of us bought right into that. Hey, we thought the revolution was right around the corner.

Charles Simmons: So you've got the Vietnam war, you've got economic conditions that are physically brutal, and racism, and, because of segregation, we generally only interacted with whites who were police.

It's cumulative. You could never say, "It's going to happen this year." Every year they would announce, "Well, there might be a riot this year, when it gets hot." You know: Negroes like to come out and riot in the hot weather. [laughs]

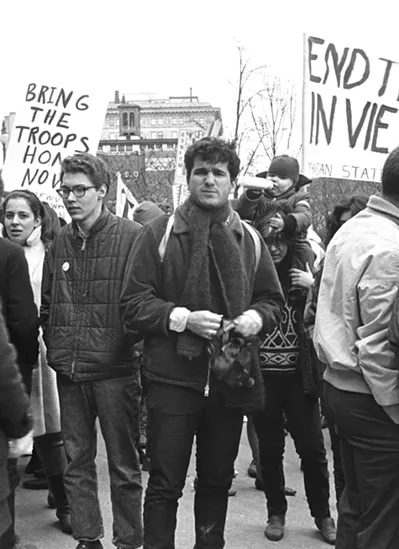

The mostly young and white radical contingent had created a small community at Warren Avenue and the Lodge Expressway, with the Detroit Artists Workshop, the Fifth Estate offices, the Committee to End the War in Vietnam, and a couple of Victorian townhouses dubbed "the Castle." The group's own troubles with the police were already boiling over.

Leni Sinclair: On Jan. 24, 1967, the whole Detroit police department came swooping down, "Lightning Dope Raid on Wayne Campus: 56 people arrested for marijuana." Oh, man. Including myself. The next thing I know I've got handcuffs on, and I'm off to jail with 55 other people. [laughs] And my case got thrown out by Judge Cockrel. And everybody else's case got thrown out. They were only after John Sinclair. They had to arrest 56 people just to arrest John. Yeah, those were the "good old days."

John Sinclair: At the end of April we'd had our maximum hippie event, a Love-In on Belle Isle. The police raided it and drove everybody off the island. So that was our relationship with the police. We hated them. And when the black people rose up against the police, nobody could have been happier than us.

Leni Sinclair: I remember how it started. The evening before the rebellion, we were invited to a party by people who had a house on Grosse Ile that extended over the water. I remember it was kind of the very tasteful, classy, laid-back atmosphere of the beautiful people. The lady of the house had a long dress on that was topless. At the time, even fashion was rebelling. And then at midnight somebody took us on an enchanted walk through this incredible garden at night. It was just mind-blowing. And then we went home, and then the next day it started. I just remember that it started with such a beautiful evening.

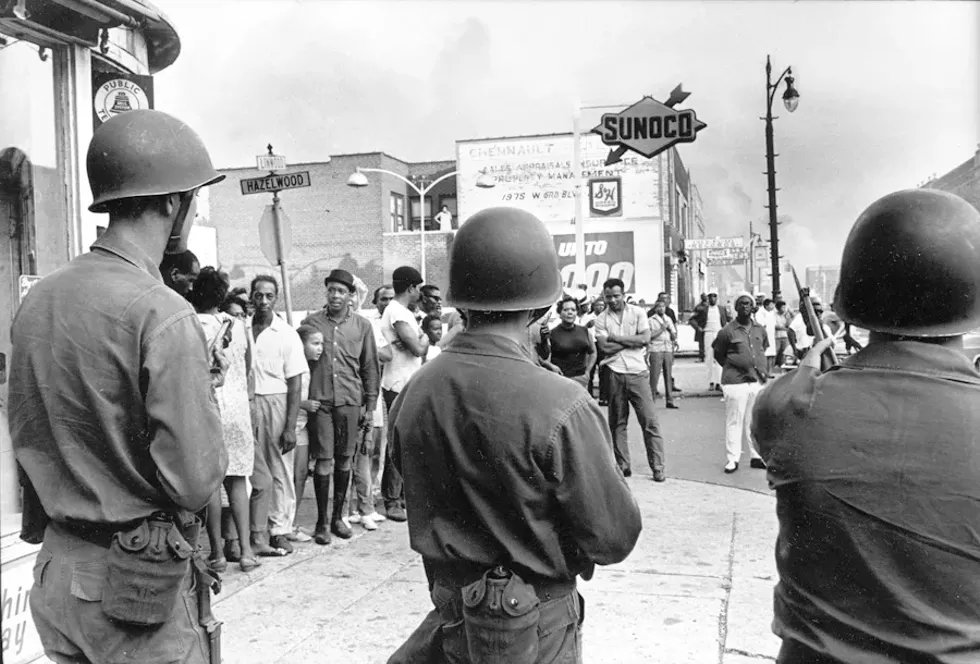

In the early morning hours of July 23, 1967, a crowd confronted a police raid on an unlicensed bar — or "blind pig."

Peter Werbe: There were longstanding grievances. When that man threw that bottle at the cop, it wasn't just because he was a little pissed off. He was throwing a bottle because of slave ships and chains and whips and what have you that coalesced right in that moment.

Charles Simmons: What happens in a riot is that all of those years, decades, centuries of abuse just explode.

Reggie Carter: When police went up in that blind pig, they found more people than anticipated at a party for returning black vets from Vietnam. Police made the decision to arrest these people. They went off and fought a war. You come back and this is how you get treated. You put your life on the line for a country that you come back to and nothing has changed.

John Sinclair: It was just a party at an after-hours joint. They weren't hurting anybody. Booting those people out of the blind pig at 5 in the morning into the paddy wagon, people just said, "Wait a minute. Fuck this!" and started throwing shit at them. And then they set some shit on fire and they overturned some police cars, and then people said, "Wow! Finally! It's bustin' loose!" That's the way I looked at it. You heard about this isolated incident, at 12th and Clairmount, and by the time you heard about it at noon it was already raging. Raging!

Pun Plamondon: The corner of John Lodge and Warren was a real center of the community in a lot of different ways, aside from being a gathering place at the Detroit Artists Workshop. It was the real heartbeat of the community, and I just happened to come down one morning and was asked if I heard about the riots.

Charles Simmons: I was sitting on the porch over [on Wabash Street] when it started. I saw smoke and then I saw people coming around with shopping carts full of stuff. [laughs] I ventured out ... I think neighbors told me there was a riot going on, and then I heard about the curfew.

Herb Boyd: When the thing went down, I was living on Richton between Lawton and Linwood, about 10 blocks north. That Monday, as soon as I heard it happened, I jumped in the car with my two sons. In fact, while we were driving around, we ran into Kenny Cockrel. [laughs] We ran into Kenny out there. And we had a nice discussion about what was going on, and then I drove on off and started to survey and look at all of the stores and people. I mean, there was still a lot of action in the street, because this was early, before the police or National Guard or any kind of Airborne could come in there and do anything.

Reggie Carter: I wanted to go out in it, and my stepfather stood at the back door and said, "You aren't going anywhere." He and I didn't get along the best, but I thank him even today for that. Because I had no reason to go out in it. Anything could have happened.

Frank Joyce: On July 23, 1967, I was in London, England, at the Dialectics of Liberation Congress, meeting with people from worldwide liberation movements. As news of what was going on in Detroit was reaching London, all of a sudden I became a person of interest in a way I had not before. Here I am at a conference where people are talking about anti-colonial struggles all over the world, and then come the headlines of Detroit in flames and troops being called in. And I was frantically trying to rearrange my travel to get back to the United States!

Harvey Ovshinsky: Where we were, the Warren-Forest area, the looting was more like a circus.

Herb Boyd: The A&P and the Kroger, some of the larger outlets — they didn't have a chance. People running up and down, cars pulling up, loading up with all kinds of groceries. If you were near anything like that or a pawn shop, or jewelry store, or something like that, it was obviously like a domino effect.

Leni Sinclair: We published some fliers during the rebellion. One of the fliers said, "Loot: It's the American way!" [laughs]

Peter Werbe: On the front page of the Fifth Estate was the headline "Get the Big Stuff."

John Sinclair: We went over on Trumbull and did some looting. We had our Trans-Love Energy cars that we used to ride around the neighborhood and pick up hippies and give 'em free rides. We saw you walking down the street, we'd stop and pick you up. That was our concept, you know? We were hippies. On acid. [laughs] So we would give people a ride with their goods that they'd gotten from the store. [laughs] We'd drive them home. We got a few goods ourselves. I remember we went into a store on Trumbull by Forest. It was a yard goods store.

Leni Sinclair: I have a picture of someone from the Artists Workshop walking down the street with a bolt of material that he had liberated from the five-and-dime. For years afterward, we used that material to sew band clothes for the MC5. [laughs]

John Sinclair: If you showed a picture of them, I could tell you which parts came from the store.

Peter Werbe: Harvey and I were out in the streets and found no hostility toward us whatsoever. We were around Trumbull and Forest, which was an integrated neighborhood, so there was integrated looting. And I remember Mayor Jerry Cavanagh took a tour while the riot was going on and said he was horrified there was a "carnival-like atmosphere." And I always wondered, "What did he want? Did he want it to be like a race riot like 1943?"

Harvey Ovshinsky: The looting was biracial. [laughs] ... The looting was permission to fight back anonymously, in a way that you couldn't get caught. Because things were out of control. I mean, when Peter and I were down there, we couldn't believe what we were seeing. There was a picture in the Fifth Estate that covered the riot of this young kid — he must have been 13 or 14 – carrying a rifle around. That was weird. It was a Fellini movie.

Peter Werbe: At the A&P [supermarket] at Trumbull and Forest, there was a young black kid about 12 years old, the whole front window was shattered and people were entering, and he had all these bags. And he would snap open these bags, like a bag boy, and hand them to people going in. [laughs]

Herb Boyd: People wandering down the street with a mannequin? I mean, come on. Just to grab something. Like mismatched shoes!

Leni Sinclair: When the rebellion started, on the first or second day, I think, we had a ball. We thought that it was just the greatest. We could drive down the street ignoring all the traffic signs. There were no cops. There were hardly any people on the street. We would see fires and everything.

Pun Plamondon: I guess you could say this was thrill-seeking: John Sinclair and I rode for three or four miles on the wrong-way side of the Boulevard, which was just unique. It was just unusual; there were no cops around. Where were the cops? The cops were out protecting the white property or firemen putting out fires. So if you were away from the action, it was true freedom.

Peter Werbe: My favorite counterculture thing was that people were playing out of the windows, "Light My Fire" by the Doors. And the cops would go running into these apartment buildings on Prentis, which was, like, student housing from one end to the other, trying to find out who was playing it.

Pun Plamondon: Have you ever gone 100 miles per hour in a car, squealing around corners and throwing gravel, losing your hubcaps and then you end up at the bar saying, "Man, wasn't that cool?" That's what it is, it's just a rush of dodging the cops. If you get caught up in it, you either get grief from the police or get shot or firebombed.

Leni Sinclair: And some of the hippies who lived in the Castle took a TV up on the roof, probably a case of beer, and were watching the riots on TV, and at the same time you could see the fire. I thought, "Wow. This is great." [laughs] But you know, that was in the first moments of rebellion. You think this is the end of the old order and the beginning of the new!

Pun Plamondon: Me and my wife at the time, we crawled up through the ceiling; there was an access door in the attic, and we got up to the roof, where you could see what looked like about 12 blocks or 15 blocks that were on fire. When you looked to the east side you could see fires. And then in about two hours you looked back to the east side and those fires had doubled. Fires on the west side had doubled. When you looked down toward downtown, you could see Grand River was ablaze. We were just smoking joints, listening to tunes and making reports to each other.

Peter Werbe: That's right! I haven't thought about that. We went up on top of the roof of John's apartment. And people were dropping acid too, which wouldn't have even occurred to me to do. And I just remember seeing fires everywhere. It looked like a city that was being bombed. And I remember thinking this was the end of Detroit.

John Sinclair: On our second floor, we were watching the riot coverage on television. We never watched television, so it was extraordinary to be sitting there watching this, 'cause then you could look and see all the fire and see smoke and all of that right out your window. We were watching TV to see what they were doing in other parts of the city, because they had kind of a secondary riot area on the east side. The report we watched most avidly was when they said the 10th precinct was pinned down by sniper fire. We were exhilarated! [laughs] I have to say the truth. We thought this was the beginning of the end.

Pun Plamondon: I had a pretty significant attitude against the government when I moved to Detroit in May. Seeing the relationship between the Detroit police and the citizens, primarily the black citizens, added to an already organic distaste for government and oppression. So that people were kicking the Detroit police's ass was just a thrill. I never took a joy in anyone getting killed. I was just thrilled about the resistance of the population against the police.

‘It looked like a city that was being bombed. And I remember thinking this was the end of Detroit.’

tweet this

Reggie Carter: You could hear gunfire, particularly at night, and there was looting on Dexter and there was looting along Davison, but it didn't penetrate into the residential community. Thing is, one or two blocks away, houses were burning up. People were living in stark fear that they were going to lose their homes, their investment.

Harvey Ovshinsky: Depending on your socio-economic-racial situation, that generally impacted how you felt. I knew black middle-class parents who were furious at the rioters.

Herb Boyd: Fires were raging all over the place. A lot of people got burned out. You had a whole block that was extinguished, on Euclid and Woodward Avenue — boom-zoom: The gas station went up and took out the whole block.

Peter Werbe: People put up "Soul Brother" signs. We had one on the Fifth Estate office — which could have been why the National Guard threw a tear gas grenade through the Fifth Estate office window.

Pun Plamondon: There was a historical marker that identified a house as the birthplace of Charles Lindbergh. In big 3-foot letters across the front porch, someone wrote, "Lindbergh was a fascist," and I just thought this was so cool. And then someone burned it down.

Charles Simmons: I had lived on Philadelphia between 12th and 14th, so I was aware of the various businesses that were burned down, and I remember there was one store, the owner was a very mean person. He was just nasty to everybody. He got burned out. So it seemed like they were selective about who they got. I'm told there was one of these rip-off furniture companies on Grand River where they had extended credit at high interest rates and all that, and people broke in there and stole all their records, [laughs] so they couldn't catch up with all the debtors.

Harvey Ovshinsky: The neighborhood of the Grande Ballroom, at Joy Road and Livernois, that was pretty much on fire, and buildings were being destroyed. And Russ Gibb came down with Tim Buckley to get their equipment, and they were shocked to see that everything was still standing at the Grande — but not around the Grande so much. And Russ asked one kid, "Why is our building still here?" And the young black kid said, "Well, that's where they make the music, man!"

Pun Plamondon: In the daytime, there'd be three or four black dudes riding down the street in their car, hanging out the windows, pumping their fists, giving the "V" sign. At night it was a lot different.

Harvey Ovshinsky: At night it was scary. There was the night riot and the day riot. By day, at least in the Warren-Forest area, it was a circus. By night, you didn't know who was going to hurt whom.

Pun Plamondon: There weren't civilian cars on the road. The only cars I remember were police cars, and they were driving around with their lights off, and some of them would have four cops to a car. And the back doors would be open, so they could jump out real quick with their shotguns. That was scary; there's no doubt about it. They would creep along at 5 miles per hour down an alley, and you wouldn't really see them unless the streetlight reflected off their chrome.

Frank Joyce: I don't remember what day I arrived back in Detroit, but by the time I got back to the city it wasn't that there were lots of new fires starting — there was just this enormous military and police presence.

Harvey Ovshinsky: It was surreal. You were watching the president on television saying, "I'm calling in the troops" — and then you'd look out your window and there were the troops. It was like he was narrating our own story.

Herb Boyd: As the National Guard and Army arrived, it was a whole different climate then, in terms of clampdown. It was just the Detroit Police Department in the first day or two. But then quickly Governor Romney unleashed the armed forces. They came here in, like, in waves, you dig it?

John Sinclair: We were clearly on the side of the residents, not the police. And especially not the National Guard.

Reggie Carter: Then you've got these weekend soldiers, folks who lived up in the northern part of Michigan and come down here with all of their prejudices. I talked to black people who were part of the National Guard at that time, and they say they overheard some whites saying they were "going out to kill some niggers."

Harvey Ovshinsky: Most of these rural folks had never really set foot in Detroit or an all-black community, so I think they were out of their element. And as a result, people got hurt. People got killed.

Charles Simmons: The guardsmen were looking very frightened. They were white guys from upstate. They had never been in Detroit. But then also some of the Regular Army, who had been in Vietnam, came.

Reggie Carter: Federal troops had experience in Vietnam, and they were more disciplined and more accustomed to dealing with situations.

Frank Joyce: To this day, one of my memes about 1967 is that the reason the 82nd Airborne federal troops really came to Detroit was to get the National Guard under control. They basically had a shoot-first, ask-questions-later mindset.

Peter Werbe: The National Guard was just shooting all the time. They shot so much they ran out of ammunition.

Herb Boyd: Many of them were as terrified as some of the people they were supposed to be corralling. I came face-to-face with several of them. They were a little nervous in the face of all the stuff that was going on. And their reflex! They heard a noise or a flash of light, their reaction was: boom! They were shooting first, asking questions later.

Harvey Ovshinsky: I do remember saying, "Well, the war is now home. It's official. Welcome to the '60s. It's there and it's here. It's everywhere."

Charles Simmons: I was listening to the radio, and they were in this neighborhood, on 12th Street or something, and the reporter was riding along while they were going to wipe out this sniper. The sniper had some small-caliber weapon compared to what the soldiers had. And you hear this pop-pop-pop-pop-pop, and then the military opened up with tanks and all kinds of shit: "WHAM!" You know, it sounded like Vietnam.

Herb Boyd: The tanks in '67, boy, you got .50-calibers on top of these tanks. They'd damn near knock a building down.

Charles Simmons: And they said, "Well, we got the sniper's nest," and they drove off. And then a few seconds later you'd hear the pop-pop-pop-pop-pop. [laughs]

Herb Boyd: I lived not too far from La Salle Boulevard. We drove over there and, in the night, we cut all our lights off, because the word got out, "Man, you don't want to have your lights on." You could see the tanks drove right across people's lawns. You could see some of the pockmarks where these .50-caliber shells had hit up against the buildings and left gaping holes.

The hippie contingent on Warren didn't escape encounters with police and the National Guard. In some ways, they invited them.

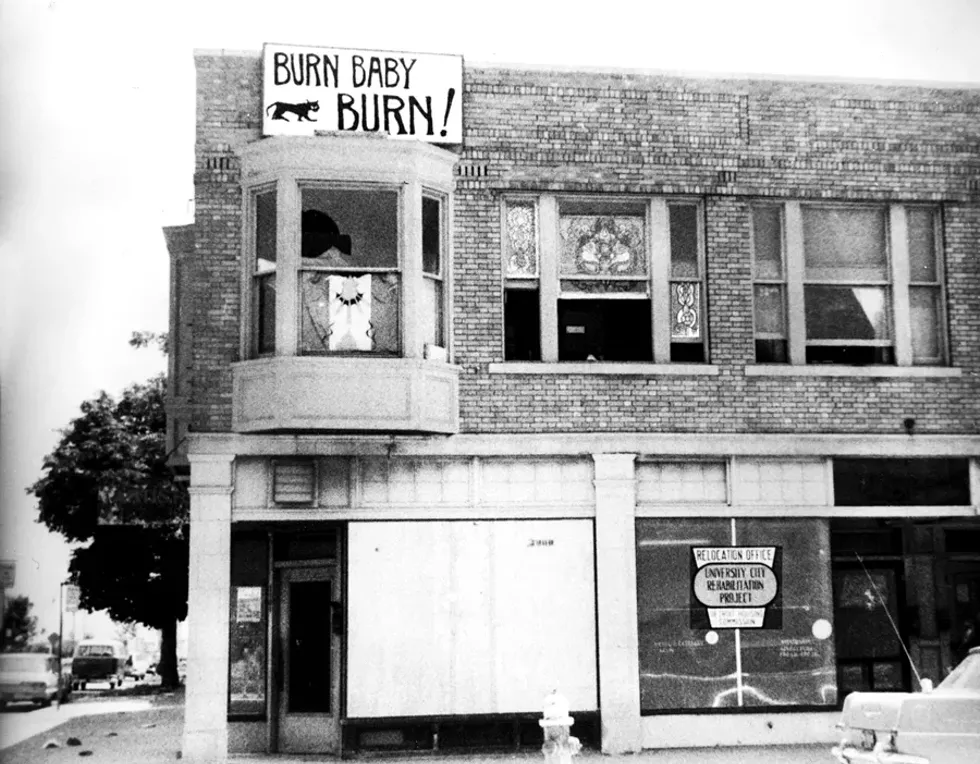

Leni Sinclair: Just before the rebellion started, Gary Grimshaw had taken a bedsheet and painted a black panther on there and "Burn, Baby, Burn," and hung it out the window. Even though that "black panther" looked more like a little black kitty-cat. [laughs] Oh, god. And then the riot started, of course that thing came down in a minute. I can't blame them for thinking we had snipers in the closet.

John Sinclair: The Grimshaw flag! I don't remember the taking-down part, but certainly we had a banner that had a picture of a black panther and it said "Burn, Baby, Burn!" hanging on the downtown side of our building at Warren and John C. Lodge. We were flying the freak flag. See, I don't think they liked that very much.

Leni Sinclair: When the National Guard came into our apartment, John had a confrontation with them. Now, mind you, our daughter Sunny was born May 4, so she was just a few months old, and I was standing there with the baby in my arms while John was hollering at the National Guard: "Get out of my house! You don't have a warrant! You can't come in!" He always had a bad temper when it comes to the police.

John Sinclair: I'm sure a lot of my memories are warped ... by terror! [laughs] It was frightening. Because they came up to our apartment and banged on the door, and then they called me by name. That was the worst part of the whole thing. And I just had my baby daughter, who was three months old, and I just snapped and said, "Well, shoot us or get out of here! You can't do this! If you're going to do this, you might as well shoot me, because I don't even care about living in this kind of an environment if you can walk into my house and just put a gun in my face! Fuck you!"

And they left! [laughs]

Leni Sinclair: The commune members in the Castle were very adventurous. They thought they would hold off the police by barricading the street, and they put out sofas and couches on the John C. Lodge. That was no deterrent to the tanks. And the cops went in and beat the people up. I think some of the people in the MC5 got arrested too. I never got the whole story.

Meanwhile, in many quarters of the city, an unsympathetic occupation by inexperienced, trigger-happy soldiers ensued. News reports talked of "snipers," and tanks rolled down main streets.

Charles Simmons: I remember going down on 12th Street and I ran into a guy who I knew who was a hustler. He had gone into a jewelry store or pawn shop and stole a lot of jewelry. He had all kinds of bling, and the National Guardsman, the soldier, was standing right there while I was talking to him. They didn't know what was going on.

Peter Werbe: All the hostility I saw, with numerous incidents personally, was threats to me from National Guardsmen and the cops. One of the bivouacs was at Central High School, and we rolled up there. This guy sees these two white guys, and says, "Can I help you?" And I said, "Yeah, we're from the Fifth Estate." And he raises his Garand and says, "I know who you are. Get the fuck out of here!"

Herb Boyd: You had this feeling that obviously it's an occupying army and the best thing, my mother told me very well, as she learned in 1943: Take cover. Go in, cut off your lights, and get down, because there's a certain madness out there. You flick the light in your apartment and suddenly they start shooting at the apartment building, scattering bullets all over the place.

Harvey Ovshinsky: And then coming home to hide under our beds because the tanks are rolling down our street, and you daren't light a cigarette, or turn on a flashlight, or attract any attention because there were reports of snipers everywhere. ... Yeah, the war came home — and we were in it.

John Sinclair: And then they had the National Guard coming down the street. Whew. That's pretty severe. I'd never seen anything like that in my life. What? A tank? On Warren Avenue? Are you nuts?

Peter Werbe: One morning, we were in a friend's apartment on Jefferson and Rivard. Why were we smoking dope in the middle of the day? Probably just because we had it. And someone says, "Wow. Look what's rolling down Jefferson." And we look out the window at personnel carriers and go, "Whoa."

Frank Joyce: Now, everybody says this, but I have to say, there is something about just seeing tanks rolling down the streets of your city that is powerful.

Peter Werbe: My wife Marilyn and I lived on Third and Delaware. After we'd gone to sleep, we heard some commotion outside at like 3 in the morning. We look outside, and this National Guard contingent in front of a Jeep has this black man spread eagle on his face wearing just a tank top and boxer shorts. I have no idea where he came from or why he was there or anything, and they're all yelling and nervous as hell, pivoting around, pointing their guns everywhere, and there was nobody on the street — at all. And they were yelling at this guy, and I said to Marilyn, while we were crouching down by this window, I said, "Those sonofabitches."

And I didn't realize on this carport right below us there was a guardsman and he turns around. I guess I'm lucky I didn't get my head blown off. He said, "Get down!" and Marilyn and I both froze, and I remember he put the bayonet — they had fucking bayonets — and pushed it against the screen and said, "I said, 'Get down.'" And I just took Marilyn and just pushed her head down and we just lay there. And I remember they got in their Jeep and they went. I don't know what happened to the guy.

Marilyn said, "Can we get up?" And I said, "Let's just wait a minute or two."

Frank Joyce: It was already known on the street, meaning in the black community, that the police, and the military, and the National Guard in particular were out of control. That they were randomly both arresting people, shooting people and killing people.

Harvey Ovshinsky: In our very earliest reporting, we took for granted that it was the rioters who were doing the sniping and the shooting. We didn't find out until later, with our investigative reports and from elsewhere, that a lot of the shootings were done by the National Guard.

Frank Joyce: I don't think there were any snipers. If there were any, it was like one or two people. And not necessarily because they were part of any political group, but simply because then, as now, we're a weaponized country.

‘I’d never seen anything like that in my life. What? A tank? On Warren Avenue? Are you nuts?’

tweet this

Herb Boyd: They were talking about [how] there was some kind of armed resistance. Well, you might have one or two that may have fired back at the National Guard, but there was never a concerted effort in that direction because it would have been absolutely suicidal.

Peter Werbe: The Detroit News and The Detroit Free Press were essentially just bullhorns for whatever the established powers in Detroit wanted to see in print.

Harvey Ovshinsky: I remember it felt like they were getting it wrong because they were focusing on what was obvious. It didn't feel like they were on the ground. You have to understand, in those days, the black community was pretty much invisible. Unless you were in trouble or arrested, young people and black people were mostly invisible to the media. And women, forget about it: They were quarantined to the society section.

Frank Joyce: I wrote a front-page piece for the Fifth Estate called, "Who killed John Leroy?" Leroy was shot in cold blood by, I believe, a National Guardsman. We were really reporting on the rebellion from the point of view not of what the rebels were doing, but what the authorities were doing.

Peter Werbe: Frank Joyce found out that a carload of black men coming home from their jobs were stopped at a National Guard checkpoint, these frightened young white guys from Escanaba. Who knows — maybe somebody made a sudden move. And these guys just shot up the car, killed a man named John Leroy, and severely maimed somebody else. I thought this was pretty deep investigative reporting that nobody did about the riot dead in Detroit until a few years after that.

Harvey Ovshinsky: We really rose to the occasion. It really tested our skills as journalists. The paper demanded that we not cover it but uncover it. And obviously the Michigan Chronicle did too. And I'm sure there was some fine reporting done at the News and Free Press; I just can't speak to it. Because their sources were mainly in the police. We had different sources. Who were we going to call?

Frank Joyce: I recall having a sense that there's going to be hell to pay for this, there's going to be a backlash for this, and just this physical destruction is going to have profound and difficult effects for the city and the people who live in it. It was sobering in that way. I do remember saying, "Hmm, maybe this isn't the whole romantic thing we imagined."

John Sinclair: After the National Guard and Regular Army troops had established control of the streets and stopped the fires, they just started picking up people, getting them off the streets. At least 4,000 people were arrested. And most were arrested just for being out after 8. People of every kind got swept up. If you went to the store after 3 p.m., you didn't get home, you know?

Herb Boyd: It was a very nervous time for a lot of our friends who were taken out to Belle Isle, getting brought into night court where Judge Crockett was letting them go left and right.

Charles Simmons: When you look at who got locked up, I'm sure some white people got arrested, but it was mostly black people. And the houses that got burned were our own houses.

Leni Sinclair: We had to leave. We gathered a few people and went to Traverse City for refuge, because we didn't know what was going to happen. It was very scary after the National Guard took over the city. It was like war, with tanks driving down the street, and we had to escape.

John Sinclair: We fled to Ann Arbor in '68 because of the street-level relations between the hippies and the police. Because after the riot, the police were really in charge then, and we just had to get out of there. We thought, "Ann Arbor? They've got like 10 police cars."

Frank Joyce: I wrote one thing in early '68 that was about the repressive response that was coming. The City Council passed a bond issue so they could buy machine guns and armed personnel carriers. There was a transition from the Big Four to the Tactical Mobile Unit. That was, in turn, followed by STRESS.

Charles Simmons: What I remember most was that the attitude of the people had changed so radically. There had been this fear of police. And that vanished after that week. And the idea of racial pride and black pride in general, and identification with African and African-American culture, there was an explosion of it — suddenly. After '67, immediately you saw people identifying themselves culturally with the dress, the attitude, and the pride, that all spread immediately after the rebellion.

Herb Boyd: The '67 rebellion kind of fueled our struggle at Wayne State University. We could put pressure on Wayne State University because they were so fearful that possibly we would have another eruption. So we created the Association of Black Students.

Charles Simmons: I wanted to be a journalist. But when I had applied for jobs as a student in Detroit, they basically laughed at me. All of a sudden, they wanted us to come in. Well, one reason was that white reporters were not allowed into the hood because of the rebellion. They would chase them out. So they had to hire people of color to go in and do interviews and stuff in the midst of all the fires and people getting shot. [laughs]

Pun Plamondon: I wouldn't say it improved things, but it definitely changed things. There's more black cops on the force, though I hope everyone quickly learned cops are cops — it doesn't matter the color of your skin.

Charles Simmons: We said we wanted black people on the board of directors, we wanted black foremen, we wanted black people as secretaries and all that. Well, they did all that. But that didn't change the nature of the exploitation of the system that continues to rip us off. We saw the face of the exploitation change its color.

Reggie Carter: Even when you have the ascendancy of Coleman Young in '73, a black mayor, and a significant black presence on City Council, and suddenly you get black judges, and so on, in the long term we've seen how meaningless that can be. Because what happens is you get a black mayor on one side of the coin and then you get disinvestment on the other side of the coin.

Harvey Ovshinsky: It was exciting. But in retrospect, it's only worth exploring, investigating, and remembering if you learn from it. If people are just commemorating and having exhibitions and writing articles and books, and the intention is just to recall it and remember it, then I think an opportunity is wasted. I think we have to try to learn from it and understand it and make sure it doesn't have to happen again. It had to happen. It had to happen. Make sure it doesn't have to happen again.

Leni Sinclair: The rebellion was a wake-up call. But you know, people never woke up. [laughs]