This refrain of inner-city lawlessness being the impetus for "white flight" appears again and again in these stories. But what if somebody told you it began in the 1940s, not as a reaction to urban unruliness so much as integration?

Of course, you can't deny that, as the disinvestment industry kicked into high gear in the 1970s and 1980s, high crime rates drove out people of means. Thanks to Detroit's famous street violence, even today struggling black families will scrape up the money to move from some of the city's more violent neighborhoods to the suburbs. But in its early stages, urban flight wasn't in response to crime, it was in response to integration. And thanks to "block busting," it proved very profitable to real estate companies.

This is part of a "counter-narrative" that has been making waves in urban studies over the last 20 years, examining the ways industrialists, developers, and real estate companies exploited the movement of millions of African-Americans to Northern industrial cities such as Detroit, playing white people against black people. It's part of a whole body of research attempting to show how racism was used by the powers that be to divide and profit from working people of both colors. It has been pioneered by historians such as Thomas Sugrue, author of The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, and enlarged upon by historians like Beth Tompkins Bates, author of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford.

Frankly, all this talk of white flight being an earlier phenomenon rooted in real estate got me curious. I spent several days this summer at the Burton Historical Collection, part of the main branch of the Detroit Public Library. It contains boxes and boxes of letters written to the mayors of Detroit by Detroiters. In the time period I was searching, the 1940s, some of the most interesting letters came from white Detroiters. And if I have to bring up the race of these correspondents, it is only because these letter-writers are so quick the bring up the subject of race themselves.

Grab a fistful of these letters from the 1940s, on almost any topic — housing, transportation, parks, jobs — and you'll find at least one letter from a white citizen outraged at having to live, commute, recreate, or work near people of color.

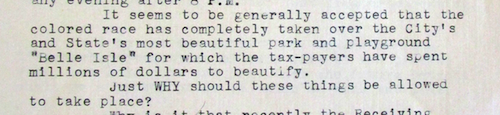

It is an ugly business to pore over these letters, but it pays off. White Detroiters of the 1940s seemed obsessed by their city services being shared by black folks. Many white Detroiters want segregated facilities, segregated streetcars, segregated parks, and for Belle Isle to be returned to whites. Here's one exasperated comment that illustrates that fact.

Another right-wing bugaboo of the 1980s, Ronald Reagan's "welfare mother," turns out to be at least as old as the career of the B-grade actor himself. Here's a golden oldie with an outraged white Detroiter who says blacks only moved up to Detroit for the "easy life."

!["My aunt's colored maid said she worked just in the summer. The Salvation Army helped her in the winter. I asked a colored woman why she left Alabama and she said, 'Detroit has such a nice well fare [sic] help station.' I would make tracks to get rid of them before we have them all in charity. Respectfully, An old Detroiter." - Courtesy the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library](https://media1.metrotimes.com/metrotimes/imager/u/blog/2460493/angry_detroiter_5.png?cb=1643053645)

Courtesy the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

"My aunt's colored maid said she worked just in the summer. The Salvation Army helped her in the winter. I asked a colored woman why she left Alabama and she said, 'Detroit has such a nice well fare [sic] help station.' I would make tracks to get rid of them before we have them all in charity. Respectfully, An old Detroiter."

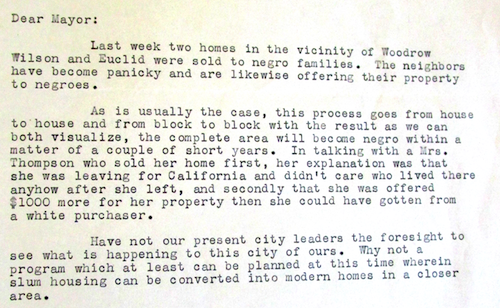

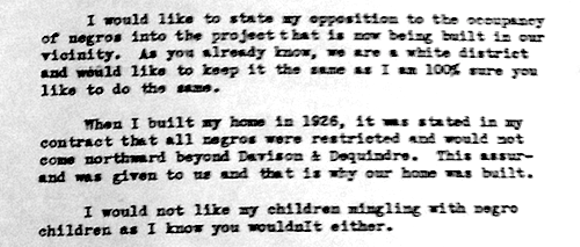

One of the most common complaints, though, is about housing. Here are your white Detroiters of yesteryear complaining that integration will damage the most valuable investment of their lives: their homes.

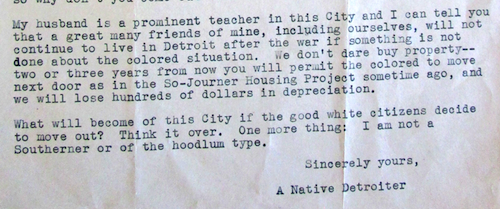

Notice how real estate is a central concern in these letters. It helps demonstrate how white opposition to integration was rooted in dollars and cents. See if you detect the veiled threat written in this 1943 letter to the mayor: If you don't do the right thing and keep Detroit segregated, we will take our money and we will move elsewhere.

Note well that the writer, like many other letter-writers, is quick to point out that she is not a hoodlum or one of the many white Southerners who've moved to Detroit in the previous years. She is a "good white citizen." (At least as long as Detroit remains segregated.)