One bright May day nearly ten years ago, in 2010, I was stooping in the dark, dank basement of a Detroit Rescue Mission Ministries facility on Mack Avenue and Fairview Street, searching for the remnants of what could be the oldest surviving outdoor African-American mural in the nation.

Lawrence Lewis, the DRMM's kindly, patient maintenance trainer, and I took turns handling his flashlight, its beams bouncing off bare brick and concrete walls, plumbing fixtures, and stacks of boards in a surprisingly cramped subterranean space below the former St. Bernard of Clairvaux Catholic Church. But the Archdiocese of Detroit shuttered the church and its school in 1990, and not long later it became the DRMM's Genesis House III, a residence for homeless women recovering from addiction. (It now provides housing for teen moms.)

There were no mural panels stored in the basement. After I'd called ahead from Chicago, Lewis had already searched the complex's dormitory, where I wasn't allowed; it had been the parish's Community School, where the mural was originally stored when it was removed around 1980. But nothing there, either. No one who worked at the facility could remember them.

I'd been looking for the five Masonite panels that made up the Harriet Tubman Memorial Wall (Let My People Go), a Black-pride mural that had been painted on panels and installed on the church facade in late 1968 by Chicago artists William "Bill" Walker, widely regarded as the "father of the community mural movement," and his late-1960s painting partner Eugene "Eda" Wade, along with church helpers.

I was following up on a lead that the mural, long believed destroyed, might still be alive...somewhere. When I'd started researching my recent book, Walls of Prophecy and Protest: William Walker and the Roots of a Revolutionary Public Art Movement (Northwestern University Press), I'd found references, including in the 1980 first edition of Art in Detroit Public Places, by critic Dennis Alan Nawrocki and Thomas J. Holleman, claiming that the panels were in storage and that there were plans to renovate and reinstall them. I'd called Nawrocki, who couldn't recall where he got that information. Neither the Archdiocese's Archives nor its Properties offices had records for the mural's whereabouts. And the Detroit Historical Society, to which I was eventually directed, didn't have the panels in its holdings, either. They were presumed lost.

******

It's not widely known in Detroit that the city played a critical role in the early development of what came to be known as the community or contemporary mural movement, in 1968-69. During that time, the riot-scarred, racially tense city was the scene of three dramatic, highly visible outdoor Black Power murals directed by Walker and Eda in ravaged east- and west-side neighborhoods. They were assisted by groups of Chicago and Detroit artists, in a post-uprising arts initiative led by a coalition of east-side churches and a community organization.

"Diego Rivera himself could not have wished for a more popular or public art," wrote Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin, in their 1975 book Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, a classic study of the city's radical Black workers' movements. (The authors were comparing the works to Rivera's Detroit Industry.) "Like most revolutionary movements and mass art, the muralist movement was little discussed in aesthetic journals." The book's first edition pictured a portion of one of the murals on its cover.

Yet these long-gone murals have been a nearly forgotten facet of Detroit's Black Arts history — indeed, in the city's art history and its exuberantly profuse mural and street art scene — as well as a largely overlooked chapter in the still-evolving history of the nationwide mural movement. By the mid-1970s, outdoor walls of hope, pride, power, and action by diverse groups of socially conscious muralists became common features in America's inner cities. In Detroit, the 1968 murals can be seen as ancestors of such modern-day programs as Murals in the Market, City Walls, Mexicantown murals, and the Grand River Creative Corridor, as well as many other individual and community projects from Bennie White's destroyed shrine to Malice Green to Chazz Miller's Public Art Workz to Nicole Macdonald's Detroit Portrait Series.

******

Walker, who died in 2011, is regarded as the originator of the mural movement owing to his instigation of the epochal Black Arts landmark, the outdoor Wall of Respect, created by him and more than a dozen other African-American artists and photographers in August 1967 on the side of a gang-graffitied grocery/liquor store in a South Side Chicago neighborhood slated for "slum clearance." (The building was damaged by suspected arson fire in 1971, and soon demolished.)

Members of the visual arts workshop of the Organization of Black American Culture conferred with local residents to identify and paint portraits of 50 "Black heroes" in the fields of activism, rhythm and blues, jazz, theater, religion, literature, sports, and dance. Instead of moderate civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr., the group pictured militants such as Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, and H. Rap Brown. (It also included Motown Records stars Smokey Robinson, the Marvelettes, and Stevie Wonder, as well as Aretha Franklin.)

The wall, wrote key participant Jeff Donaldson, later a founder of the AfriCOBRA collective and art department chair at Howard University, was "a national symbol of the heroic black struggle for liberation in America."

Walker, 40 (at the time), was the senior member of the collective and the only one who'd had experience as a muralist, beginning when he was a student on the GI Bill at what's now the Columbus College of Art and Design, from which he graduated in 1953. From the late 1960s to the 1990s, the Birmingham, Alabama native created several dozen outdoor murals in Chicago that addressed the harsh realities and enduring hopes of the urban Black experience, social and racial justice, and the "unity of the human race," as he put it, which are considered among the movement's highest achievements. Once called a "prophet with pigment," Walker — who co-founded the Chicago Mural Group, now the Chicago Public Art Group, in 1971 — painted walls with a morally righteous, missionary zeal, believing they could save mankind from destruction and provoke social change. (Three 1970s walls survive, and are periodically restored, on Chicago streets.)

The Wall of Respect became the scene of political rallies, poetry readings, jazz jams, and other performances. It drew visitors from all over the city and beyond, as well as undercover cops and the FBI. An article in the December 1967 issue of Chicago-based Ebony magazine spread news of the mural nationally, and by the summer of 1968 similar walls began rising in other Black neighborhoods, most notably in Boston and St. Louis. Spurred by countercultural, protest, and ethnic-pride movements, socially engaged "people's art" murals and organizations soon proliferated in major U.S. cities.

Detroit was where the movement moved first after Chicago, in early spring 1968, becoming (at least for a while) the center of a different kind of "revolutionary art" in response to Rivera's monument to labor and industry at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Rebecca Zurier, an associate professor of art history at the University of Michigan, became interested in the murals while teaching a class on the history of art and culture in Detroit. She e-mailed, "It's interesting to me that Walker and Eda painted soon after the 1967 uprising — in the neighborhoods that suffered the most damage — and their work became part of the process of Detroit becoming, and redefining itself, as a majority-Black city."

******

In Detroit, the newly formed Churches on the East Side for Social Action — a coalition of 36 interracial Protestant and Catholic churches — called the 37-year-old organizer Frank Ditto from Chicago to start a grassroots organization in the struggling neighborhood.

Ditto was the key link. An East Texas native who had picked and chopped cotton as a kid, Ditto was working as a cab driver in Chicago in the early 1960s when he became a school desegregation activist. He organized a South Side community group and marched regularly with comedian-activist Dick Gregory in Chicago in the mid-1960s to protest the racist school system; he also accompanied Martin Luther King, Jr. on his final Selma to Montgomery March in 1965.

Ditto founded the East Side Voice of Independent Detroit in a storefront office on Mack Avenue, blocks from St. Bernard Catholic Church, ministered by Father Thomas J. Kerwin, a CESSA founder. Ditto couldn't have arrived at a more opportune moment — weeks before a police raid in an after-hours club stoked long-smoldering racial tensions that flared into the five-day rebellion, leaving 43 dead.

According to a June 13, 1969 profile in Time, ESVID was "a civic action organization that is the moving force behind a dozen 'black pride' projects in the slums, where burned-out shops still define the fury of the 1967 riots." Funded by New Detroit, a coalition of community leaders that formed to find solutions to the violence, projects included Black Panther-like youth patrols, police monitoring, neighborhood cleanups, playgrounds, a free employment agency, and a weekly newspaper, The Ghetto Speaks. The projects would also soon include murals.

Ditto had the idea when he saw the Wall of Respect on a trip back home to Chicago in late 1967. "I was so fascinated each time I saw that," Ditto told me in a 2008 interview. (He died in 2011.) "There was such a sense of pride and dignity and history. I couldn't get it out of my mind." Ditto knew Bill Walker, a constant street presence, from his days as an activist in Chicago, and invited him to Motown. "I admired Eugene's and Bill's work in Chicago. We decided we wanted to put up some murals in Detroit."

******

Walker and Eda shuttled between Chicago and Detroit a number of times through 1968 and early 1969, usually in Eda's Volkswagen bus. At the time, the Baton Rouge-born Eda, 29, was a middle school art and history teacher who'd soon earn his MFA degree from Howard University (and was later an art professor at Chicago City Colleges). The two often also stayed at the St. Bernard Church Rectory as they worked intermittently on the three murals. Sometimes they hauled panels they (and others) had painted in their studios in Chicago to install in Detroit.

"Me and brother Eda were fortunate to get the project," Walker told me, in one of our many interviews before he died in September 2011. "Things in Detroit were not good at all, but we worked toward painting about love, unity, and understanding, as best we could. People understood — they had a desire to get along. We had a good group of people."

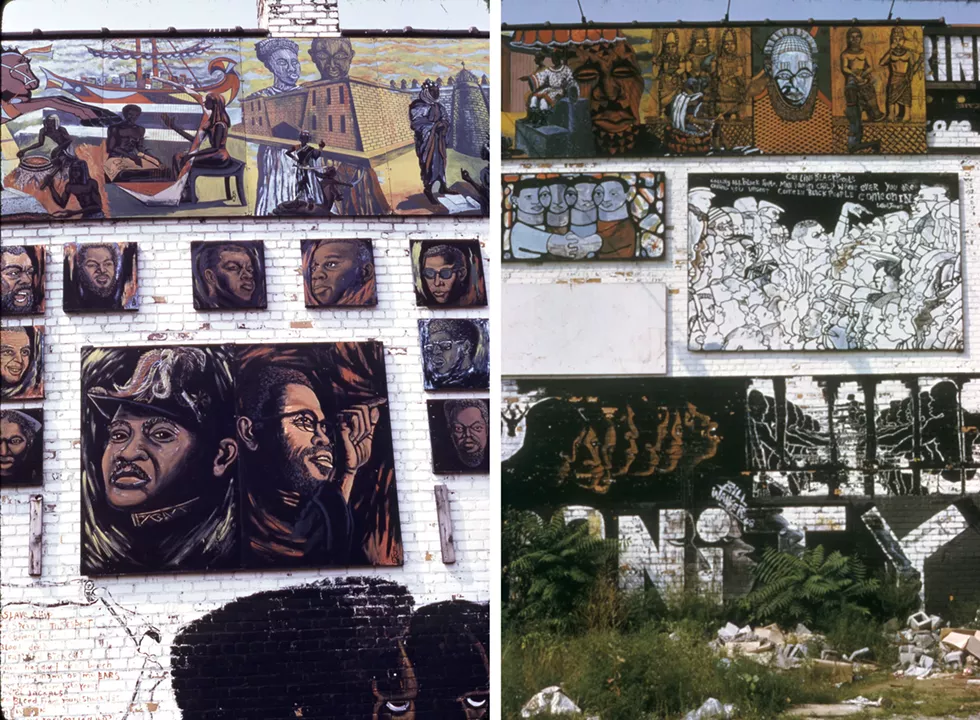

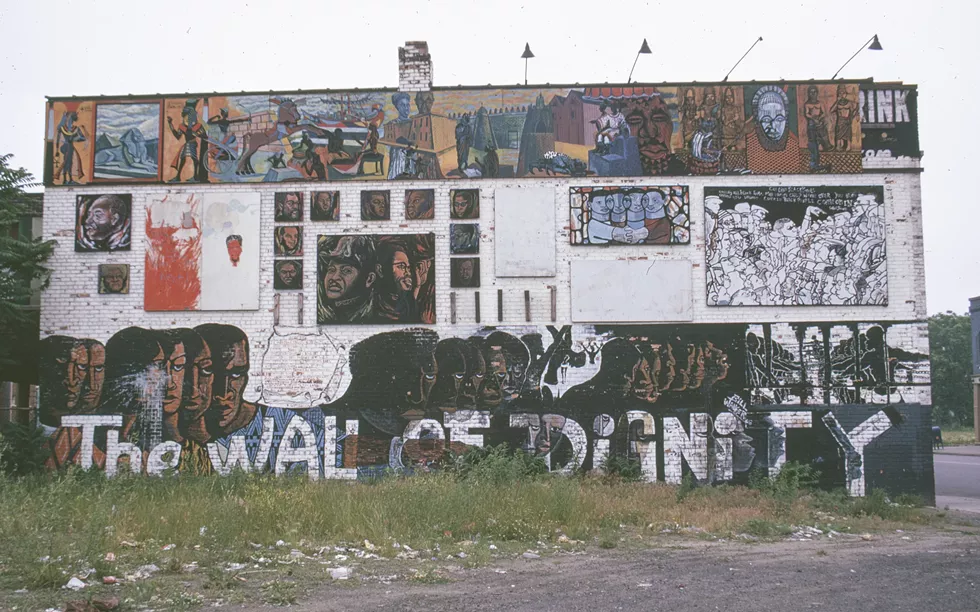

Wall of Dignity, believed to be the nation's second community-based Black Power mural, stood across the street from the church on the northeast-facing wall of the Fairview Gardens building at 11000 Mack Avenue, which housed a roller rink (and former wrestling hall) and other shops. The colorful, collage-like gallery featured Eda's Masonite panels showing glorious ancient African civilizations and his portraits of Black American leaders, like one of Malcolm and Marcus Garvey together; Walker's brick-painted black, white, and red scenes depicting Blacks in bondage and liberation; and paintings by other artists. Walker added an illustrated text panel of Amiri Baraka's poem "S.O.S," which begins "Calling all black people..."

With four auto plants within a mile in all directions, the wall drew a captive audience of commuters, factories' "radical workers" included, observed Georgakas and Surkin.

An early version of the mural was pictured on the cover of the April 22 issue of ESVID's weekly The Ghetto Speaks, calling it a "monument to Blackness." Besides Walker and Eda, the paper credited Edward Christmas, who'd also worked on the Wall of Respect, Al Saladin Redmand (or Redmond), a Chicago Muslim activist and newspaper publisher, and helpers.

The wall, said the article, "carries a message for the Black moderate, the militant, even Uncle Toms and white people. It says: 'HERE WE ARE: WE HAVE BEEN JAILED, ROBBED, AND BEATEN. WE HAVE BEEN PERSECUTED, MURDERED, AND KIDNAPPED, BECAUSE WE ARE BLACK...WE ARE PROUD OF OUR BLACKNESS.'"

The mural, which cost $2,000 in materials and expenses, was dedicated in May 1968; like the Wall of Respect, it became a site for rallies, concerts, and other events. Ditto trained local teens to be guides when school classes and other groups visited the mural, and civil rights icon and Detroit resident Rosa Parks attended an ESVID youth political organization event. "We involved the community, with respect and participation," Ditto told me, adding that the mural "lifted peoples' spirits and had a positive effect." (After auditors found accounting irregularities in 1973, ESVID became a nonprofit; Ditto resigned as a trustee from New Detroit a year later, citing corruption, according to Sidney Fine in his Violence in the Model City.)

A five-alarm fire "destroyed" the Fairview Gardens building on June 13, 1972, according to the Detroit Free Press. The Wall of Dignity remained relatively intact, except that a couple of Eda's heroes' portraits were lost or stolen after the blaze. The building with its mural stood at least for another few years, until it was demolished.

******

Wanting to organize a mural in the area of the riots, Walker and Eda approached the clergy of Grace Episcopal Church through their CESSA contacts. The artists were also drawn by its highly visible wall facing 12th street (now Rosa Parks Boulevard) at Virginia Park Street, blocks south of the uprising's epicenter. They met with the Reverend Father Marshall Hunt, who was white, and associate rector Arthur Williams, who was Black, and discussed the idea of bringing this new form of social public art to a primarily conservative Black church. The artists made plans to involve Detroit artists and to begin painting during the 12th Street Black Arts Festival, which was to take place at the church July 22-27 — the first anniversary of the rebellion.

Still, the artists' group found themselves caught between the church's mainline civil rights and its more liberal, activist elements, exemplifying the tensions of the times. The mural movement was so new and unproven at this point, there were bound to be growing, or learning, pains.

"We took a definite risk in doing the wall," Hunt told the Free Press in a November 4, 1968 article, pointing out that more than half the church's members were "well-to-do blacks" who lived on the city's northwest side and 20 percent were from the local neighborhood; the rest were white. "We decided to make our move into the community with the wall." The church contributed $900 for scaffolding, paint, and other materials, with some left over for the artists.

Walker, the Wall of Pride director, recruited about eight Detroit artists through the church's community program. Many were affiliated with the Contemporary Studio group, the city's earliest Black gallery and studio venue, dating to 1958. According to Walker's memory, other muralists, and an August 9, 1968 Detroit American article, participants included: LeRoy Foster, Robin Harper (Kwasi Asante), Henry King (Henri Umbaji King), Jon Lockard (Jon Onye Lockard), James Malone, Arthur Roland, Gerald Simmons (Nana Akpan), and Bennie White (Bennie White Jr. Ethiopia Israel). Several of these artists went on to create some of Detroit's — and Michigan's — best-known African-American community murals and public mural commissions.

The group painted figures on the church annex's roughly triangular upper roof facade that highlighted the "contributions of black people, whether they be controversial or well-liked," said Walker, in the November 10 issue of The Living Church magazine. After the design was drawn up, each of the artists contributed their own sections and images, interweaving tropes of uplift, heritage, and militancy. Different groups painted at different times.

Many images called for revolution and liberation, from Africa to Afro-America. There were Walker's renderings of Malcolm and Amiri Baraka (with his poem, "Black Art"); Eda's Egyptian scenes and his portraits of Stokely and Rap inside a Black Power fist; W.E.B. DuBois flanked by leaders of African postcolonial nations; Asante's Muhammad Ali; as well as figures such as James Baldwin, Miriam Makeba, Nina Simone, and Aretha. The novel sight of a group of Black men up on a roof painting a mural slowed traffic and drew gawkers, according to news articles.

The community response was "overwhelmingly positive," Hunt told the Free Press, but some church members were "less than enthusiastic" about some of the figures. Lockard — who'd done a couple nightclub murals on 12th Street in the mid-1960s that burned in the riot — said he was painting a portrait of the Rev. Albert B. Cleage, Jr., the civil rights activist and pastor at Detroit's Shrine of the Black Madonna, when Grace Episcopal clergy told him that some congregants had complained — they objected to Cleage's Black Christian nationalism. "They wanted me to remove it, and I just refused," Lockard, then 78, told me in a 2010 interview. (He died in 2015.)

Walker, who said he was unaware of religious politics in Detroit, defended Lockard in a tense meeting with church leaders. "The image was not meant to antagonize," he told the American. "It was meant to help people understand each other." In the end church members presumably painted out the portrait. The mural was entirely whitewashed by the mid-1970s.

"Bill Walker brought a spark that ignited something," recalled Lockard, a longtime art professor at Washtenaw Community College and a founder of the Afroamerican and African Studies department at the University of Michigan who created some of the state's most notable murals in the 1970s and '80s. "It was an interesting era — you didn't have the support of the established art community. It was grassroots, renegade grassroots. Not renegade like when you think of renegade today, with graffiti. The established artists wouldn't dare get involved."

******

The final mural led by Walker and Eda in Detroit also had its provocative elements.

Father Thomas Kerwin, the white pastor of the racially mixed St. Bernard Catholic Church, and Allen McNeeley, the Black director of the church's Community School, commissioned the artists to create the Harriet Tubman Memorial Wall (Let My People Go). The Archdiocese's Inter-Parish Sharing Program funded materials, transportation, and meager salaries. According to the mural's dedication booklet, children enrolled in the school's summer history class taught by Detroit Institute of Arts educator Christine Schneider, a nun, suggested the theme of freedom and slavery, drawing parallels between biblical and civil rights examples.

Walker and Eda worked on the five Masonite panels in Chicago and Detroit, and installed them on the facade of the church in December, along with church helpers. "It took a lot of courage on the part of the priest to allow us to do this particular wall," Walker told me, referring to the mural's activist content. "There was a time he would have been regarded as a heretic."

Reached at his home in Colorado Springs in 2010, the 86-year-old Kerwin credited the reform-minded Archbishop of Detroit John Cardinal Dearden. "He never balked or gave a note saying, 'You better be careful,'" said Kerwin, who left the church in 1969, moved to Flint, married, and became a community mental-health counselor. "Everything was open-ended, and I thought that was amazing." (Kerwin died in 2016.)

The Harriet Tubman Memorial Wall commemorated the famed abolitionist, the "Moses of her people," who led fugitive slaves to the free North and Canada. The mural's images equated the civil rights movement with that of the Israelites in bondage to Egypt, chronicled in the Book of Exodus. In the dedication booklet, McNeeley urged visitors to ask who was the modern-day Pharaoh and who were the people yearning to be "free of oppression, political exploitation, poverty, fear, unemployment, ignorance, apathy, wars, and hate."

Yet Walker told the January 25, 1969 issue of the Michigan Chronicle that the "Biblical Wall" was intended to "serve as a healing function between the races rather than any form of protest."

The mural's three sections (on five panels), each about 20 feet high, resembled elongated stained-glass windows. The central panel above the doorway, designed and painted by Eda, pictured Moses confronting the Pharaoh, both Black figures, demanding that he "let my people go" to the Promised Land against a backdrop of ancient Egyptian monuments.

Walker designed and painted most of the two side panels, which emphasized the religious dimension of the Black freedom struggle, from historical to modern times, linking Tubman and unshackled worshipers in the west panel to a civil rights march of both mainstream and and nationalist figures in the east panel. King, Malcolm, and Nation of Islam leader and former Detroit minister Elijah Muhammad (Elijah Poole), clutching their holy books, were in the forefront of a procession that included Charles Diggs, Jr., Michigan's first African-American congressmen, and Shirley Chisholm, the first Black congresswoman.

While Walker was installing these panels, he said a black limousine pulled up and uniformed agents from the Fruit of Islam, the NOI's security wing, got out and studied the portrait of Elijah. Walker asked them what they thought, and one of them said, "We'll let you know." Walker said to let him know now, because he was heading back to Chicago. He added the mural was "done with respect" on behalf of the church community. An agent replied, "You executed it beautifully."

The mural was unveiled on January 7, 1969. Not long later, back home in Chicago, Walker got a call from Father Kerwin, who said that the mural had been defaced: the image of Elijah with his Koran had been covered with green paint. Recalling the meeting with the FOI agents, Walker wasn't surprised. He said the portrait had likely been erased because Elijah forbade images of himself depicted with Malcolm, owing to the latter's bitter split from the Chicago-based Nation in 1964.

Walker offered to come back to Detroit and repaint the panel for free, but Kerwin told him, "No, no — we want it to stay the way it is." And it did stay that way until the mural was removed, more than a decade later.

******

Back at the Detroit Rescue Mission Ministries' Genesis House III in 2010, it turned out that a few staffers knew Allen McNeeley, who still visited the old parish. He was then chief chaplain for the Detroit Fire Department. I got his number from an officer at a nearby firehouse and called him from the parking lot.

McNeeley told me that the decaying panels had been removed from St. Bernard's facade around 1980 while he was administering the church. "We had to take it down because of the weather and it was becoming dangerous — pieces were flying off," McNeeley explained. The panels were stored on the second floor of the school building until they could figure out what to do with them. He mentioned having talks with the Detroit Historical Society. The archdiocese closed the parish by 1990, before the DRMM took over the property.

Recently, the U-M's Rebecca Zurier sent me a February 25, 1990 Free Press article I'd been unaware of. In it, Deacon McNeeley, then a coordinator with the Archdiocese's Office of Black Catholic Affairs, announced plans to turn the closed Holy Ghost Church into a Black Catholic Historical Museum, forming what the newspaper called "a chronicle of a community's faith in the face of racism." He'd already collected artifacts from shuttered churches, and planned to include the Harriet Tubman Memorial Wall panels (which he erroneously called the Wall of Dignity).

But the museum "never came to fruition," e-mailed John Thorne, pastoral associate at Sacred Heart Parish and former director of the archdiocese's Office of Black Catholic Ministry. AOD archivist Steve Wejroch said he didn't know what happened to the artifacts, adding that plans to annually exhibit them also never panned out. And Allen's daughter, Judith McNeeley, of Detroit, e-mailed she did "not have details on the artifacts," either.

Somewhere along the way the mural disappeared. Almost 10 years ago McNeeley told me, "someone could've trashed or stolen the panels."

******

In all, despite the conflicts, Walker felt that his Detroit stint was an important passage in his life and work, in the city's Black arts and power movements, and in the mural movement. "It was a hell of a time," he said. "People were very involved in the movement, in what was happening. People were friendly and concerned about doing the right thing. All the people were starting to come together... The spirit of the people, especially the young people, was tremendous. And they were all trying to do something — they were all trying to do the right thing. That's all I can say. I was privileged to be a part of it, to be a part of the people trying to do the right thing."

Adapted from Walls of Prophecy and Protest: William Walker and the Roots of a Revolutionary Public Art Movement. Copyright 2019 by Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.