Why Detroit's medical marijuana ordinance gets it wrong

If you listened to the rhetoric of Detroit City Councilman James Tate over the last year or so, you'd think he was going to help create a legal framework for medical marijuana dispensaries.

But after examining the language in the ordinance passed by Detroit City Council this month, many boosters of medical marijuana are wondering if Tate's legislation is designed to shut them down completely.

Dispensaries had cropped up all over the city, and lack of regulation did appear to result in what the investing class calls "market exuberance": Dozens of fly-by-night operations opened in the city, sporting green crosses and groan-inducing business names. From the beginning, Councilman Tate must have known he had a winning issue for his constituents in Northwest Detroit’s District 1, which has its fair share of sweet, old church ladies who apparently don’t understand medical marijuana at all. Take this post to Tate's Facebook page:

Presumably, crime rates at neighborhood doctor's offices will skyrocket, but ... well, that's enough fun at the expense of poorly informed people. (Needless to say, the people repeating myths about dispensaries have been proved to be blowing smoke.)

The ordinance has some elements that seem reasonable. Anybody hoping to open a new medical cannabis dispensary will have to submit to a background check. And all the stores that close will have 30 days to remove their signage. (Note well that any other business has 60 days to do so; clearly those little old ladies are in a hurry to blunt the visual impact of Detroit's green boom.) But what's really raised the ire of medical marijuana advocates is the way the legislation seems designed to shut down dispensaries completely. And they say the ordinance itself violates the law.

According to Rick Thompson's Weed Blog, unfair provisions in the ordinance include the requirement that medical marijuana facilities be 2,000 feet from liquor stores, other special-use properties, and other dispensaries, without recourse to requesting a variance. The requirement for liquor stores is 500 feet, with the option of requesting a variance. Or, as Thompson says:

A 2,000-foot barrier from other dispensaries is outrageous; one medical marijuana distribution center in the space where 9 liquor stores are located (at 500 feet apart)? How is this fair, or reasonable, or a proper way to administer your city? Answer: it’s not. It is not intended to be fair, nor is it intended to be reasonable, nor is it intended to be justifiable to anyone other than Councilman Tate.

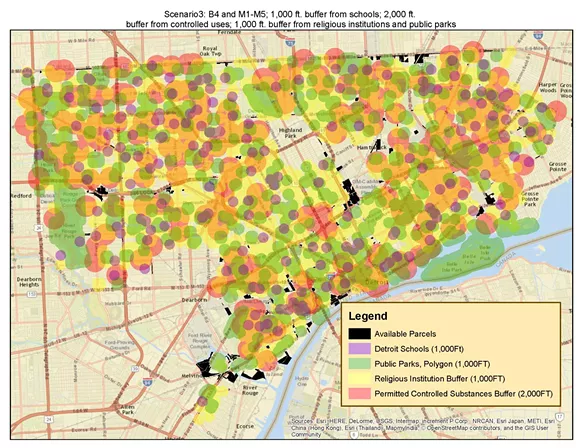

The difficulties of setting up stores that meet those guidelines was illustrated in a map presented by Councilman Tate himself.

Each cluster of dots represents areas where the ordinance prohibits a dispensary, with a few "available parcels" in black. Yes, people had felt that the dispensaries needed to be regulated, but the map gives the appearance of regulating them right out of business.

Although the ordinance says it's not intended to prevent patients from getting their medicine, it does contain a curious wording that gives some observers pause. It reads that these business must be "operated by a registered primary caregiver that distributes medical marihuana, in a manner authorized by the Act, to registered qualifying patients as defined by the Act." That wording is seen as problematic, because narrow state rulings have interpreted the law to mean one caregiver may sell the medicine to his registered patients.

As blogger Thompson points out, in the narrowest interpretation of the law, the ordinance "would allow a single caregiver to dispense medical marijuana to their five allotted patients under state law, and that is it."

"The current business model used by dispensaries in cities all across the state, including Detroit, is to provide medical marijuana to anyone who possesses a medical marijuana patient or caregiver card," Thompson says. Restricting dispensaries to one caregiver and his approved patients simply isn't economically viable. Thompson says: "That is a business model that would not sustain any storefront operation, and the cities who license these distribution businesses know it."

In other words, if you pass background checks, find a suitable location in these gerrymandered zones, you may establish a business that is almost certain to lose money.

What's more, Thompson argues that may of the provisions, such as bans on applying for variances, conflict with the Michigan Medical Marihuana Act. So the ordinance passed by Detroit City Council may not simply be unfair, it may be illegal as well.

The ultimate irony is that, in other states, medical and recreational marijuana sales are driving tax revenues ever higher. And yet Detroit is prepared to not only try to balk this bonanza with an overly broad ordinance, but may actually end up paying legal fees or damages for creating an illegal law.

Which is enough to make you wonder: What's wrong with these opponents of dispensaries?

Are they high?