Anyone who has parented a teenager knows that kids sometimes do things that defy all logic. That's because their brains have not fully formed, and their ability to make sound decisions is impaired.

Given that fact, it's not surprising that the overwhelming majority of nations don't lock kids up kids under the age of 18 and throw away the key, keeping them behind bars for the rest of their lives, even when the crime they commit is murder.

In fact, according to a federal lawsuit recently filed by the Michigan branch of the American Civil Liberties Union, there's only one country on the planet where that occurs.

That would be America.

And of the 50 states in this country, Michigan is among the harshest when it comes to dealing with juvenile offenders convicted of first degree murder. Kids as young as 14 are automatically charged as adults (unless a prosecutor seeks a waiver) and, if convicted, are automatically sentenced to prison without possibility of parole.

That's wrong, on so many levels.

On the one hand, the state recognizes as fact the general lack of maturity among adolescents. That's why there are laws prohibiting them from voting, or consuming alcohol or smoking cigarettes.

They just aren't considered capable of making responsible decisions. Yet, that same state will send to prison for life a person such as Henry Hill.

In 1980, Hill was a 16-year-old student at Saginaw High School. He had an IQ of 61 and a third-grade reading capability. While with two of his cousins at a park, one of those cousins shot and killed another young man, Anthony Thomas.

Hill was convicted by a jury of first degree aiding and abetting murder, and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Now 46, he's been behind bars for nearly 30 years.

Hill is among nine plaintiffs listed in a lawsuit filed in Detroit's U.S. District Court. The suit, which names Gov. Jennifer Granholm, Michigan Department of Corrections Director Patricia Caruso and Barbara Sampson, chair of the Michigan Parole Board, alleges that Michigan's "sentencing scheme" for juveniles convicted of murder and sentenced to life without parole "constitutes cruel and unusual punishment and violates their constitutional rights."

"These life without parole sentences ignore the very real differences between children and adults, abandoning the concepts of redemption and second chances," Deborah Labelle, an attorney for the Michigan ACLU's Juvenile Life without Parole Initiative, says in a prepared release. "As a society, we believe children do not have the capacity to handle adult responsibilities, so we don't allow them to use alcohol, join the Army, serve on a jury or vote — yet we sentence them to the harshest punishment we have in this state — to die in adult prisons."

We've been keeping an eye on this issue for years. Nearly four years ago, this paper wrote about it in a cover story ("Juvenile injustice" Dec. 13, 2006), in which we quoted Rosemary Sarri, a professor at the University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research.

"We now know why kids do the crazy things they do," Sarri told us at the time. "They are fundamentally different than adults."

As we reported then, neuroscientists using MRI scans have been able to show key differences in the frontal brain lobes of adolescents and adults, that part of the brain is linked to "regulating aggression, long-term planning, mental flexibility, abstract thinking, the capacity to hold in mind related pieces of information, and perhaps moral judgment."

That quote came from a report produced by the groups Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

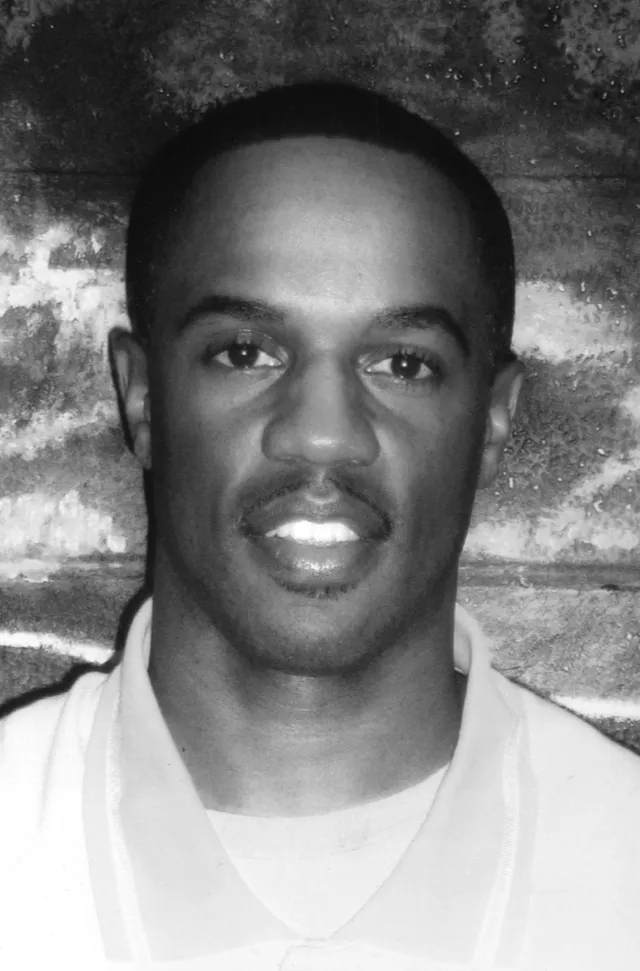

Among the plaintiffs in the recently filed ACLU lawsuit is Damion Todd, whose case played a prominent role in our 2006 story.

Todd was 17 when he shot and killed 16-year-old Melody Rucker of Detroit. Todd maintains that he was trying to scare others who allegedly shot at him and a group of friends at a party, and that Rucker was accidentally hit.

With his appeals exhausted and attempts to obtain clemency denied, he faces the possibility of dying in prison unless the law is struck down.

Michael Steinberg, legal director for the Michigan ACLU, says there's good reason to hope the law will be changed. Recently, he says, in the case Graham vs. Florida, the U.S. Supreme Court, on a 6-3 vote, ruled that juvenile offenders cannot be sentenced to life imprisonment without parole for non-homicide offenses.

Steinberg says that the much of the rationale used by the majority in ruling on that case could be applied to the Michigan case.

The Michigan ACLU, Steinberg notes, has been attempting to get the Michigan Legislature to change state law for the past eight years. The reluctance of lawmakers to address the issue, combined with the Supreme Court's ruling in the Graham case, prompted the civil liberties group to take the issue to federal court.

"We decided it was time to try and jump-start the process by challenging the current system in court," Steinberg tells News Hits. He points out that the intent of the lawsuit isn't to prevent all juvenile killers from spending their lives in prison. What it does want to do is provide an opportunity for those capable of reform to one day be released.

"Want to stress that just because an individual may become eligible for parole, doesn't necessarily mean he or she will be released," Steinberg explains. "What we're saying is that the Parole Board should be able to review the individual circumstances of person who committed crime as kid."

Granholm's office did not respond to a request for comment by press time.