A Wilderness of Error:

The Trials of Jeffrey MacDonald

Errol Morris

Penguin Press, $29.95, 544 pp., hardcover

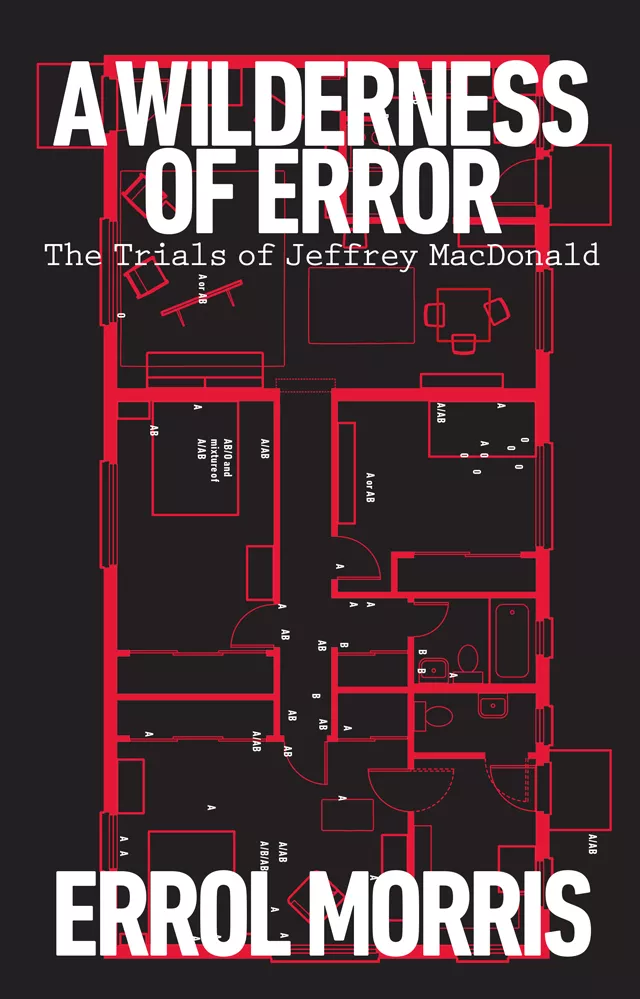

In 1970, the family of Jeffrey MacDonald, a Green Beret and successful military doctor, was brutally murdered. MacDonald, who had several stab wounds, said that a band of acid-crazed hippies had invaded the house. Prosecutors, however, soon began to suspect MacDonald himself. Though cleared in a military investigation, civilian criminal charges were brought against the doctor nearly a decade later and, despite the existence of a woman who confessed to numerous people that she was with the "hippies," MacDonald was convicted. Joe McGinniss wrote about the case in the hugely successful Fatal Vision, which was later the subject of Janet Malcolm's famous The Journalist and the Murderer. McGinniss, who initially befriended MacDonald, later claimed he was a psychopath, and Malcolm argued the truth would never be known.

In his mammoth new book, A Wilderness of Error (Penguin, hardcover), renowned documentary filmmaker Errol Morris claims they are all wrong. Morris' 1988 film, The Thin Blue Line, freed a man wrongly convicted of murdering a police officer, and he hopes his new book may have a similar effect on the MacDonald case, which is back in court this month on the basis of new DNA evidence. We recently caught up with Morris in New York to discuss the book.

Baynard Woods: The first thing I wanted to ask, before getting into the book, is about the transition from filmmaking to writing. You've recently been writing blogs for The New York Times, and this is your second book in two years. I've read about you saying you had writer's block. How did it come about that it finally ended?

Errol Morris: I think it's because The New York Times asked me to write, and at first I said I don't think I can do this, but then I started and I kept doing it. I've always wanted to be a writer and I never thought it would ever happen, and maybe I've become one — I'm not sure.

Woods: In this book, you talk about how people wouldn't let you make a film because they knew that MacDonald was guilty. Did you have any problems getting a publisher to do it?

Morris: It happened in an odd way. I originally intended to write this for The New York Times. It was going to be part of my online series of essays, and I had written about 60,000 or 70,000 words, and I asked my editor, "Can we do this as a long series of essays, multi-part essays?" and he asked around and said, "You know, the case is over 40 years old and it's just not something we're set up to do — an essay in 10, 12, 20 parts." My agent at the time, at Wylie, said, "You should do this material as a book." He sold it. ... I was encouraged to do it. No one ever did that for a movie version. Never happened.

Woods: In your last book [Believing Is Seeing], you are primarily concerned with how we know things. But in this book, while you are still interested in the nature of evidence, your concerns seem much more ethical. I wonder if you want to talk about the relationship between what we know and what we do with it, or how we act.

Morris: That's an interesting way of thinking about it. There is an epistemological element to this book, for sure, because it is about the nature of evidence and how we use evidence to come to a conclusion about things. And there is also this ethical dimension — I mean there's something so deeply wrong with how this story has been covered. I'm bothered by this whole story on so many different levels. I'm bothered by it as an investigator, because I feel it was not thoroughly investigated. I'm bothered by it on a narrative level, because I think that it is often overwhelmed by a false narrative that took the place of truth. And I'm disturbed by it on an ethical-moral level, because I believe Jeffrey MacDonald shouldn't be in prison. There's a thing about justice here because I don't believe justice was well-served. It's in fact, for me, a terrible miscarriage of justice. So in answer to your question, it's all of the above.

Woods: On the narrative level, I was wondering if you wanted to prove McGinniss and Malcolm wrong to show that you can deal with all the evidence and still tell a really good tragic story — or that he can be innocent and it is still a good story. It seems like you criticize them for putting art over the truth.

Morris: I would put McGinniss' problem different than Malcolm's. I don't think McGinniss put art over the truth. I think he put his financial interests over the truth, pure and simple. I hesitate to call Fatal Vision a work of art. I would prefer to call it a work of truly hackneyed journalism. The fact that it was so successful is itself disturbing. You can see unmistakable signs of how that narrative changed as he decided to write a book affirming [MacDonald's] guilt and attacking his character. For McGinniss, it was not enough to repeat the verdict of the court. He had to say that Jeffrey MacDonald not only did it, but he was the kind of man who could have done it. That part of the book I find the most disgusting because he had to create a fake character out of whole cloth. If I call it hackneyed journalism, I mean it. I find it pathetic. ... Those passages I quote from Heroes [an earlier, largely autobiographical work], where McGinniss talks about having dreams about the maiming of his little daughters. ... MacDonald never had these kinds of dreams, McGinniss did. To me, it's not simply ironic — though it is ironic. It suggests McGinniss was writing about himself, ultimately, and not about MacDonald. Not to compare this to The Thin Blue Line, a case I worked on more than 25 years ago, but a man was convicted and sentenced to death for crimes he did not commit, because the courts had upheld his conviction. That's the whole point. There was a miscarriage of justice.

Woods: Do you think that The Thin Blue Line gave you the stamina or wherewithal to undertake a project that has been such a quagmire for so many people — the feeling that you could uncover the things that either laziness or mendacity or whatever has kept other people from?

Morris: I'm not convinced that I can. I have this deep need at least to try. The passage in The Journalist and the Murderer that disturbed me and still disturbs me is when Janet Malcolm is seated in front of the folders of evidence ... about how she decided not to look at the evidence because this evidence doesn't speak for itself. That would be like trying to prove the existence of God from looking at a flower. Think about that passage. It is trying to tell you that evidence means nothing. But proving the innocence or guilt of a criminal defendant is not like trying to prove the existence of God. It relies on evidence and if you are not willing to follow that evidence and that logic, you have nothing.

Woods: Now that Helena Stoeckly [the woman who matched MacDonald's description, was seen near the crime scene, and confessed to numerous people], the narcotics agent who worked with her, and the judge are all dead, is there a part of you that wishes you'd come to this earlier?

Morris: I can answer that really simply. The answer is yes. For any investigator who really wants to get to the bottom of things, the realization that so much time has gone by, that there are many questions that can never be answered about this case. Although, the whole situation was messed over from the start.

Woods: Now that it is a book, do you think it could be as successful as a film and have an impact like The Thin Blue Line?

Morris: I don't. I struggled so hard just to write the book. My plan was to finish the book and get it out there and hope that it has some effect on the case. ... I could write a book about the evidence and about the nature of narrative and how narrative can undermine evidence and how ultimately the search for truth must prevail over the desire for storytelling.