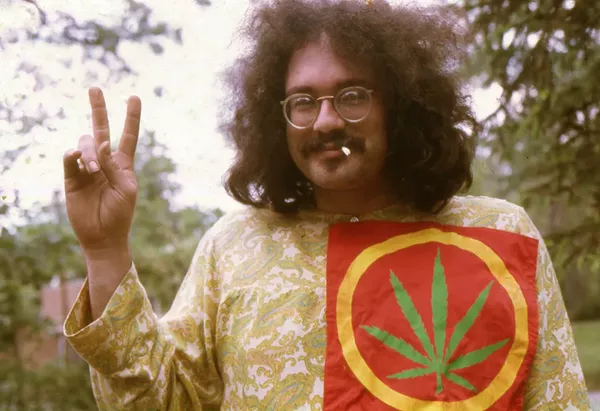

Most folks around here figure that the beginning of the drive for marijuana legalization in Michigan started in 1971 with the John Sinclair Freedom Rally in Ann Arbor. Those with a bit more acumen might waggle a finger and point out that in 1967 The Michigan Daily, the student newspaper at the University of Michigan, ran an editorial calling for the legalization of marijuana.

But to look for the first marijuana legalization group in Michigan, you really must go further back — all the way back to 1964, to Sinclair's first arrest for sales and possession, after which he started a local chapter of the national group LEMAR, which stood for "legalize marijuana."

"I got a flyer in the mail from New York from Ed Sanders and Allen Ginsberg where they announced the formation of New York LEMAR and the first marijuana demonstration," says Sinclair. "I thought what a great idea. ... Of course, in those days marijuana was dope. It was a narcotic, and they were terrified of it."

LEMAR ran some meetings and spoke to a few groups, but they couldn't get much traction with most political activists at the time — not the Detroit Artists Workshop, which Sinclair helped found, or with the Black Panthers.

"The Black Panthers said, 'What the fuck kind of revolutionary movement has got to do with drugs?'" Sinclair says. "'We like to get high, but what the hell does that have to do with the revolution?'"

LEMAR drifted off the landscape, and there was no activity of consequence until that Michigan Daily editorial. Then, in 1969, Sinclair was busted for the third time and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

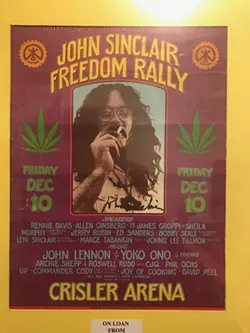

It was his then-wife, Leni Sinclair, who ran around and organized people to try to get her husband out of jail while his appeal made its way up the legal ladder. When the idea of the Dec. 10, 1971, John Sinclair Freedom Rally came together, Leni and Peter Andrews, who produced the concert, went to New York to scrounge up musical talent to play at the concert. The Sinclairs were friends with activist Jerry Rubin, and Rubin was friends with John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

"What really tipped the scale was John Lennon," Sinclair says. "When John Lennon announced he would be coming to Ann Arbor to be on this thing, it turned everything around — from public opinion to the legislature to the judiciary."

Aside from Lennon and Ono, most of the rest of the musicians on the poster are less than household names, and little from the local scene. The Contemporary Jazz Quartet backed up a couple of national figures. Stevie Wonder and Bob Seger, who did play that night, came on at the last minute, too late for their names to be on the poster.

Actually, the day of bigger impact to the marijuana scene came the day before the rally, on Dec. 9, 1971, when the state legislature passed big changes to Michigan's then toughest-in-the-nation marijuana laws. Marijuana was reclassified as a controlled substance rather than a narcotic, and penalties for possession and sales were scaled back.

Three days after the rally, Sinclair was released from prison on bond. His appeal was adjudicated by the state supreme court on March 9, 1972. The state court declared the law unconstitutional, thereby making marijuana legal in Michigan for 22 magical days before lawmakers got another law passed.

The new law took effect on April 1. As a pushback, Sinclair and his compatriots created the first Hash Bash.

"We thought it was an April Fool, that's why we had the Hash Bash," says Sinclair. "If you're going to have a new law, so what? We're going to get together in public on the campus of the University of Michigan and smoke marijuana."

A few hundred people showed up, and the next couple of years saw a lot of easing marijuana strictures in the state. Sinclair was recruited to the Human Rights Party, which garnered seats on city councils in Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti, and laws were passed in Ann Arbor and East Lansing that made marijuana possession a civil offense punishable by a $5 fine.

Rep. Perry Bullard, D-Ann Arbor, made some headway on the pro-marijuana front in the state legislature in 1977, but was ultimately blocked by the black political block. Sinclair, who was working for MI NORML at the time, says that Detroit Sen. David Holmes claimed that his son was a "dope fiend" who had started out on marijuana, and Rep. Daisy Elliott, who had successfully sponsored the state civil rights act the year before, attacked Bullard with an ashtray.

That pretty much ended Sinclair's activism on the issue, as he moved on to the struggles of trying to provide for his family. If anybody was working to legalize marijuana in Michigan as the Reagan years came on — with its "crack attack" ramp-up of the war on drugs — they weren't being heard.

Except for the Hash Bash, that is — which has endured unscathed to this day.

The 1980s was also the decade during which growing high-quality marijuana right here in Michigan — in fields, in houses and buildings — became a big thing, creating the infrastructure of today's production and distribution system, which remains underground. The early 1990s produced more of the same, except with a presidential candidate who claimed he had not inhaled joints with something of a wink and a nod. When Bill Clinton won despite his own marijuana "use," it signaled a changing mood in the nation.

"When they passed the medical marijuana law in '96 in California, I thought that was the beginning of a new period that we had something good to look forward to for the first time in 20 years," Sinclair says.

In 1996, Adam Brook, who was managing the Hash Bash, invited Sinclair to speak there. Sinclair had been passing up invitations to speak at events, but he had just released an album of his poetry with music, so he took the opportunity to get his name back out there. The same thing happened with an opportunity to speak at the Boston Freedom Rally. Sinclair was back around the marijuana legalization movement, but by now there was a new army of activists taking things in hand.

‘We like to get high, but what the hell does that have to do with the revolution?’

tweet this

The everyday civil disobedience of producing and using marijuana fueled the new activists, who became bolder and bolder. Rainbow Farm was a pro-marijuana campground in southwest Michigan where annual Hemp Aid and Roach Roast festivals were popular from 1996 to 2001, drawing the likes of Tommy Chong, Merle Haggard, Sinclair, and other legalization activists. The fests even made a High Times magazine list of top worldwide stoner destinations.

But Rainbow Farm also drew police attention. A tax raid on the place also revealed a basement garden with 200 plants, which led to charges against the two owners, Tom Crosslin and Rolland "Rollie" Rohm. In September of 2001, the situation culminated in a stand-off with state police and FBI agents, during which the owners burned the buildings on their property over a three-day period and exchanged gunfire with police. Both Crosslin and Rohm were killed. It was a tragic blow to one of the state's few identifiable centers of activism.

But that didn't kill the movement, either. Tim Beck remembers going to his first Hash Bash around the same time, and listening to national activist Jack Herer speak. Herer told the crowd that if 300 attendees gathered 1,000 signatures each that they could put medical legalization on the ballot. The effort failed, but it put a gleam in Beck's eyes.

"I thought, 'What the hell,'" says Beck. "I began exploring the situation in the city of Detroit. I realized how easy it would be to get something on the ballot in Detroit, only 6,000 signatures. Nobody was doing drug policy reform ... I said medical, that will work."

The second try worked, and in August 2004 Detroiters voted in favor of medical marijuana in the city. Ann Arbor did the same thing in November.

"It won and all these activists gravitated to it," says Beck, who at the time was executive director of MI NORML. They ran successful initiatives in places like Ferndale, Traverse City, and Flint. The elections accustomed people to voting about marijuana, and attracted the attention of the Marijuana Policy Project, a national policy reform organization. The MPP got involved with the Safer Michigan Coalition, and they ran a successful petition drive and campaign for the Michigan Medical Marihuana Act in 2008.

Activists continued to run successful initiatives in cities across the state. However, they had switched from medical marijuana efforts to decriminalization, lowering law enforcement priority, and legalization votes in Detroit, Ferndale, Berkley, and Grand Rapids — 14 successes in all. These led to the effort by MI Legalize, a coalition led by East Lansing attorney Jeffrey Hank, to get a vote for recreational legalization on the ballot in 2016.

That effort was beset by lack of money and a hostile state legislature. MI Legalize gathered enough signatures, but not in the six-month period that opponents argued they had to be collected in. Then, in a cynical move, after the petitions had been turned in the spring of 2016, the state legislature passed a law that retroactively made the petitions ineligible because of the signature-gathering period. The MPP, which had helped the MMMA in 2008, was more concerned with a more sure-thing legalization effort in California.

Marijuana activists geared up for the next election. The MPP, fresh off the California victory, partnered with MI Legalize to create the Coalition to Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol. Infighting was kept to a minimum, and major players maintained disciplined messaging. Signatures were gathered within the legal time period, and while state officials dragged their feet, in the end they had no choice but to put the question on the ballot.

CRMLA also made the move to back Dana Nessel for Attorney General, helping her score a victory at the state Democratic nominating convention. In return, Nessel strongly supported Prop. 1, the marijuana legalization law, as did gubernatorial candidate Gretchen Whitmer. The result was that Michigan voters chose legalizing marijuana by 56 to 44 percent.

"It's the first time in the history of Michigan that we've influenced the mainstream since the John Sinclair Freedom Rally," says Sinclair, who earlier this year sued the state to declassify marijuana as a schedule 1 controlled substance in Michigan.

The cast of key activists who turned the tide in Michigan is long and wide, but it pretty much starts with John Sinclair, who kept getting busted for marijuana — so he tried to change the law.

From our beginners guide to cannabis issue.

It's a new era for marijuana in Michigan. Sign up for our weekly weed newsletter, delivered every Tuesday at 4:20 p.m.