During the 1950s, the Detroit Lions were a football dynasty — an era that local author Richard Bak revisits in his new book, When Lions Were Kings: The Detroit Lions and the Fabulous Fifties (Painted Turtle). Coached by Raymond “Buddy” Parker and featuring such Hall of Famers as quarterback Bobby Layne, halfback Doak Walker, and linebacker Joe Schmidt, the Lions won four division titles and three National Football League championships between 1952 and 1957. However, there was rarely a Black face in the huddle. In this excerpt, Bak explores the team’s slow-footed desegregation, a subject with particular resonance as today’s NFL struggles to accommodate activism within its now majority-Black player ranks.

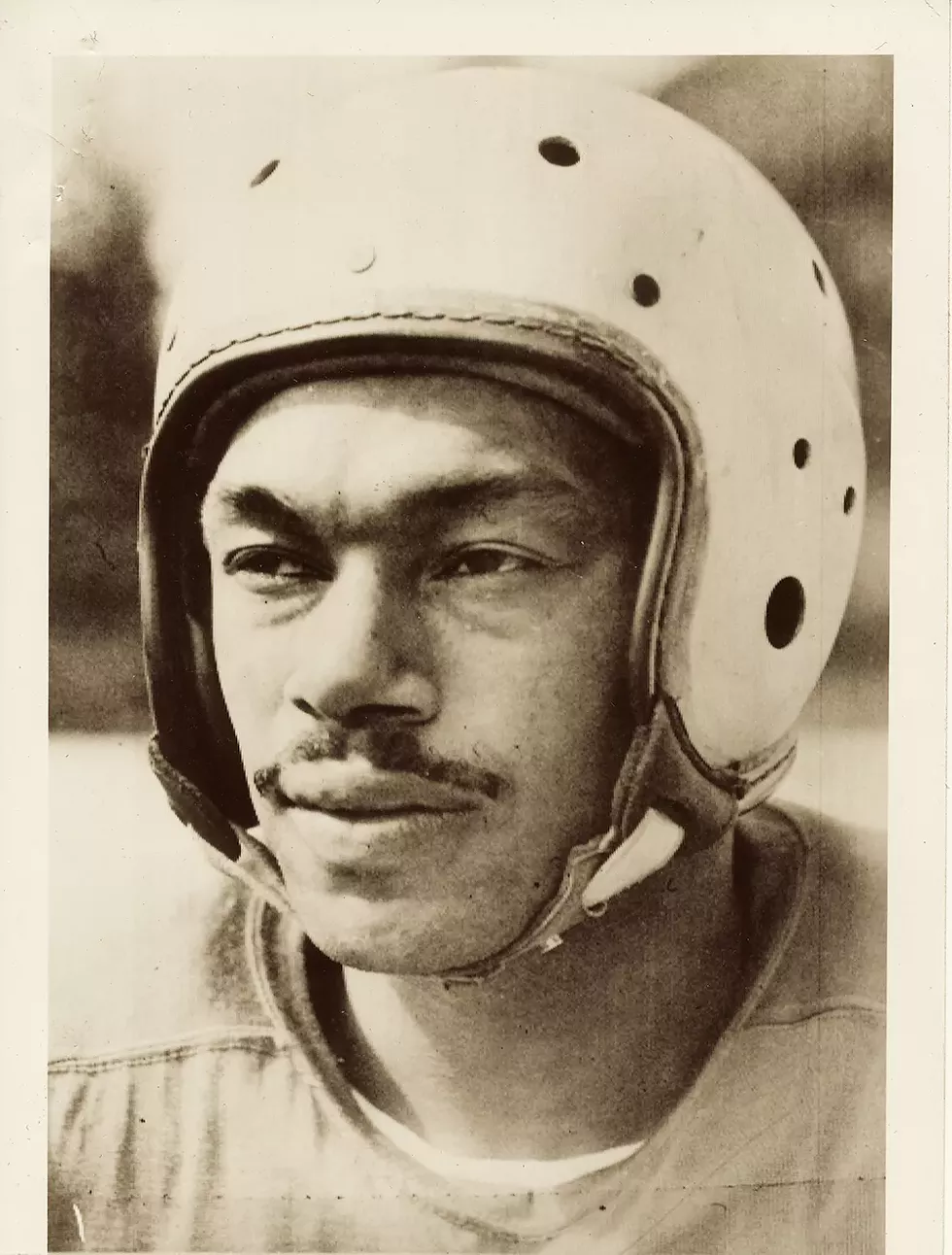

"I didn't take nothing from anyone. In a football game ... I hit the Black guy as hard as I hit the white guy. I didn't think about color when I was playing. On occasion I'd get a little trouble. I was called 'nigger' a few times, and all that would do was make me play a little harder, hit them harder."—John Henry Johnson

tweet this

On Dec. 1, 1955, the Detroit Lions assembled at Briggs Stadium for what normally was "defense day," Thursdays being the only day during the regular season when Buddy Parker had the entire team practice in full pads. This time, however, Parker devoted the day to tweaking some offensive formations as the team prepared for its upcoming game with the Bears.

That same afternoon, several hundred miles to the south, a serene-looking seamstress named Rosa Parks went ahead with her own version of defense day, protecting her seat and her dignity in a calculated act of defiance that kicked off the modern civil rights movement. The activist was arrested after refusing to surrender her seat to a white man on a segregated city bus in Montgomery, Alabama. The ensuing Montgomery bus boycott thrust a local Baptist minister, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., onto the national stage and highlighted the difficult task of remedying the state-sponsored discrimination that the Supreme Court had just declared unconstitutional. The previous year, in the landmark case of Brown vs. the Board of Education of Topeka, Supreme Court justices had decided that the separation of races in the classroom was inherently unequal. A historic precedent had been set, and ultimately discriminatory practices in housing, bank lending, employment, and voting would be struck down as well. This monumental societal shift wouldn't come easy. It would take years of marches, sit-ins, beatings, hosings, bombings, murders, and federal intervention before the web of discriminatory state and local laws, ordinances, and practices — known collectively in the South as Jim Crow — was dismantled.

Detroit, to where Parks and her family moved in 1957, was considered by many southern Blacks to be more desirable than the dusty little towns they continued to leave in droves during the postwar years, even as increased automation and consolidation in the auto industry caused the number of unskilled factory jobs to dry up. Upon their arrival in Detroit, transplants discovered to their dismay that in many respects it was still like living in an alien environment. The only difference was that segregation in the North was de facto, the patterns of discrimination ingrained through custom, not law.

Although Detroit's Black population would pass 400,000 during the 1950s, until late in the decade there was no Black representation on city council, there were no Blacks playing for the Detroit Tigers, and policemen patrolled the streets in segregated squad cars. Detroit was the home of the modern labor movement and the membership of the United Auto Workers was one-quarter Black, yet there still wasn't a single minority on the UAW's executive board. When a local firebrand named Coleman Young Jr. visited the offices of The Detroit News, every reporter, editor, printer, and secretary he encountered was white.

"I did stumble upon a couple of Black men mopping the floor in the lobby," the future mayor recalled in his autobiography, "and when I asked how many Blacks worked in the building, they said, 'You're looking at 'em.'"

During the 1950s, the dilapidated, overcrowded east-side neighborhood where most Blacks lived was in the process of being demolished in the name of urban renewal. (Disaffected citizens called it "urban removal.") The residents being displaced by the Chrysler Freeway and Lafayette Park were not welcome in most areas of the city or the suburbs. Whereas Detroit was roughly one-quarter Black by the late 1950s, in its three largest suburbs — Dearborn, Livonia, and Warren — there was, collectively, just one African American resident for every 2,000 whites. In Grosse Pointe, realtors worked with property owners to employ a secret coding system that kept "undesirables" out. Dearborn, where Parker and several other members of the Lions organization lived, was so overtly racist under Mayor Orville Hubbard that a Montgomery newspaper covering the bus boycott featured it in a 1956 story about northern cities whose conditions most closely resembled those found in the Jim Crow South.

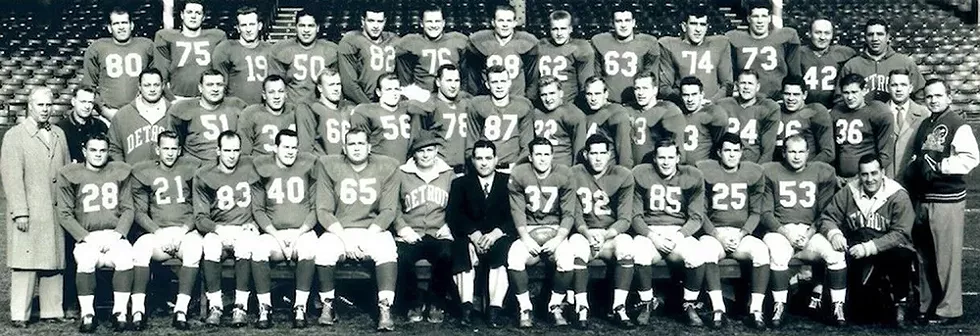

Intentionally or not, during the 1950s the Lions were a microcosm of the segregated Motor City. Between 1950 and 1957, there never was more than one Black on the roster at any given time. For most of that period, there were none. During a six-season stretch, from 1951 through 1956, the Lions fielded just two Black players — defensive linemen Harold Turner and Walter Jenkins — who appeared in a total of five regular-season games between them.

Bill Matney, Russ Cowans, and other members of the Black press considered the Lions a historically racist organization. Just how fair that characterization was remains open to debate. It was true that the championship squads of 1952 and 1953 didn't have a single Black face in the huddle, making the Lions the last team to win an NFL title with an all-white roster.

But it also was true that, a few years earlier, the entire league had just seven Black players — and three of them wore Detroit uniforms. Were the Lions discriminatory, or merely discriminating, when it came to fielding Blacks? Buddy Parker insisted it was the latter. "I just hadn't been able to find one I thought good enough to play for me," he said in 1957.

Parker claimed he had tried to make a deal for Joe Perry, who in 1953–54 became the first NFL back ever to rush for 1,000 yards in consecutive seasons, but San Francisco "wouldn't even talk to me about Perry."

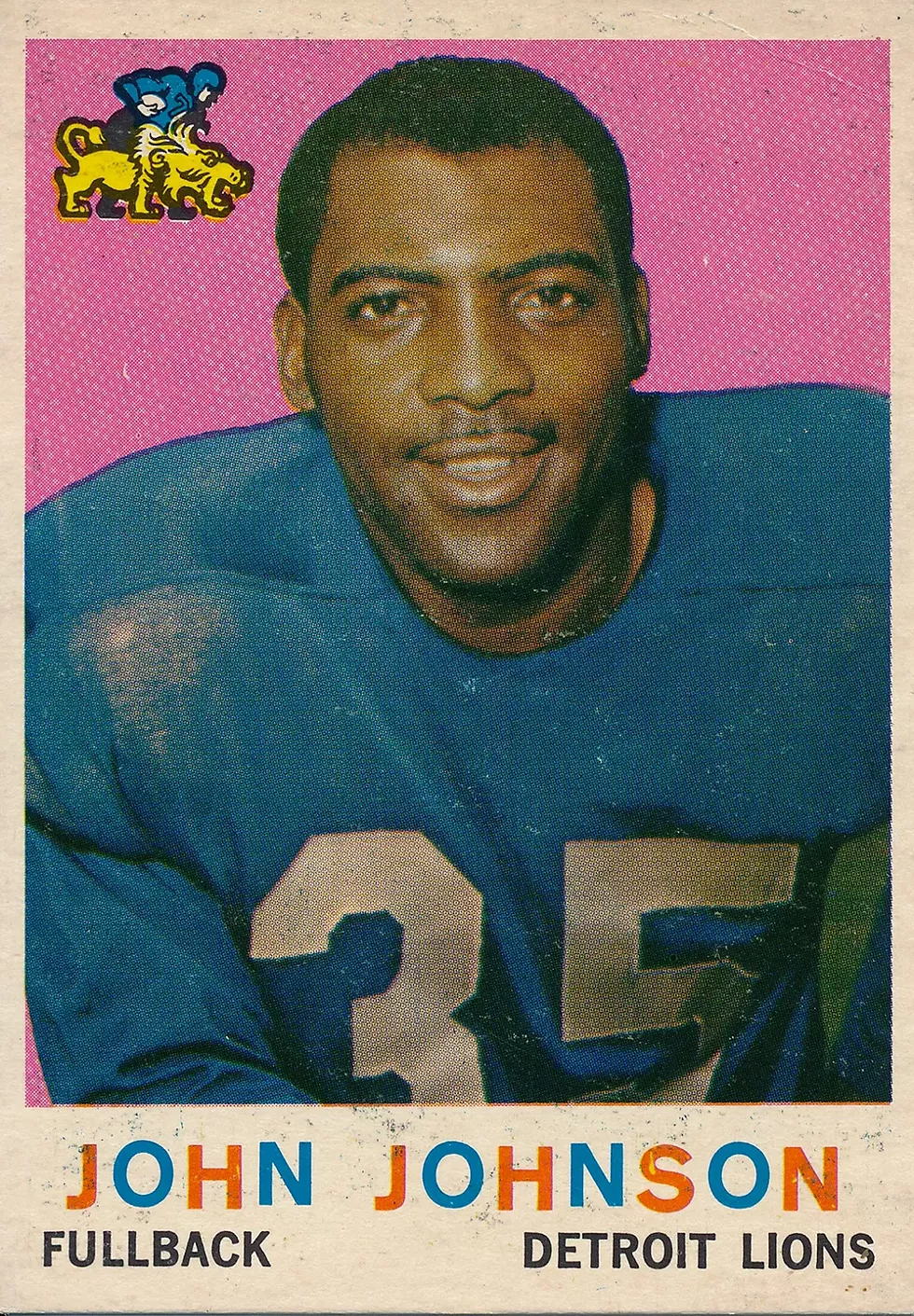

However, the 49ers were willing to talk to Parker about Perry's teammate, the intimidating John Henry Johnson, who had spent his first three NFL seasons rattling molars on both sides of the scrimmage line. In the spring of 1957, the 49ers, looking to upgrade their defense, agreed to send Johnson to Detroit for Bill Stits and Bill Bowman. "Johnson is the kind of fullback I've been trying to get for quite a while," Parker said.

Johnson was the only Black player on the Lions' roster in 1957, but his presence still represented progress, of a sort. For a long spell, no Blacks were considered good enough to play in the NFL. A modest number of African Americans had suited up at various times during the league's wild, formative stage between 1920 and 1933. Historians have identified at least 13, though none played on the succession of short-lived franchises that operated in Detroit during this period. Then the door slammed shut.

The freeze-out coincided with the ascendancy of George Preston Marshall, who became the sole owner of the Boston Redskins in 1933 and subsequently moved them to Washington, D.C. An innovator who introduced fight songs, halftime shows, marching bands, split divisions, guaranteed gates, and a balanced schedule to the NFL, Marshall's showy broad-mindedness narrowed to an unseemly recalcitrance on matters of race. "We'll start signing Negroes," he famously said, "when the Harlem Globetrotters start signing whites."

For a dozen seasons, 1934 through 1945, not a single Black person played in the monochromatic NFL. Moreover, no Blacks were selected in the league's annual college draft, from its inception in 1936 through 1948, despite there being no shortage of quality players to choose from. Throughout the Great Depression and World War II, club owners, even those moderates who might have considered lifting the unofficial ban on Blacks, followed the persuasive Marshall's lead.

World War II saw a steady migration of southerners, Black and white, to the industrial North to work in the defense plants. In overcrowded Detroit, America's "arsenal of democracy," it was a combustible mix. There were incidents of white factory workers refusing to work alongside Blacks. Violence accompanied attempts to desegregate public housing. Black newcomers experienced the same institutionalized racism they had hoped to leave behind in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. They found some favorite activities, such as an excursion ride on the Bob-lo boats or dancing at the Graystone Ballroom, limited to a single day set aside each week for "colored customers."

In June 1943, the tensions erupted into a full-fledged race riot that remains among the deadliest in the nation's history. Days of rioting claimed the lives of 34 Detroiters. Twenty-five of the victims were Black, and most of them had been shot by the nearly all-white police department. Martial law was declared, and federal troops were brought in to restore order at bayonet point.

"Younger people don't know how ugly America was in those days," said Wally Triplett, who once had a scholarship rescinded when the university discovered he was Black. "It was just a horrible time." Triplett, a Penn State Nittany Lion turned Detroit Lion, remembered fans in some stadiums screaming "Kill that nigger!" during his college and pro careers.

The battles on the home front exposed the hypocrisy of the world's mightiest democracy fighting for freedom in Europe and Asia while tolerating a segregated society at home. In 1946, the same year Jackie Robinson signed a minor-league contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers (he would integrate major league baseball the following season), the NFL began its own process of reintegration.

It was slow and not entirely by choice. The defending champion Rams, who had just relocated from Cleveland to Los Angeles, were pressured by the commissioners of Memorial Coliseum to field Black players or lose the right to play home games at the publicly funded stadium. In response, the Rams signed halfback Kenny Washington and end Woody Strode, both of whom had played in the UCLA backfield with Robinson before the war. That same autumn, the All-America Football Conference started play, creating new opportunities. By 1949, the AAFC fielded 20 Black players, nearly three times the number who played in the NFL.

No AAFC team benefited more than Paul Brown's Cleveland Browns, whose roster of stars included fullback Marion Motley and linebacker Bill Willis. Acceptance came grudgingly, Motley said. "Of course, the opposing players called us 'nigger' and all kinds of names like that. This went on for about two or three years, until they found out that Willis and I was ballplayers. Then they stopped that shit. They found out that while they were calling us names, I was running by 'em and Willis was knocking the shit out of them. So they stopped calling us names and started trying to catch up with us."

The Lions fielded their first Black players in 1948, the year ownership changed hands and Bo McMillan was hired. McMillan's success at Indiana was due in part to his having run an integrated program. According to the Afro American newspaper, the 1947 Hoosiers "had more colored gridmen than any large squad in the country."

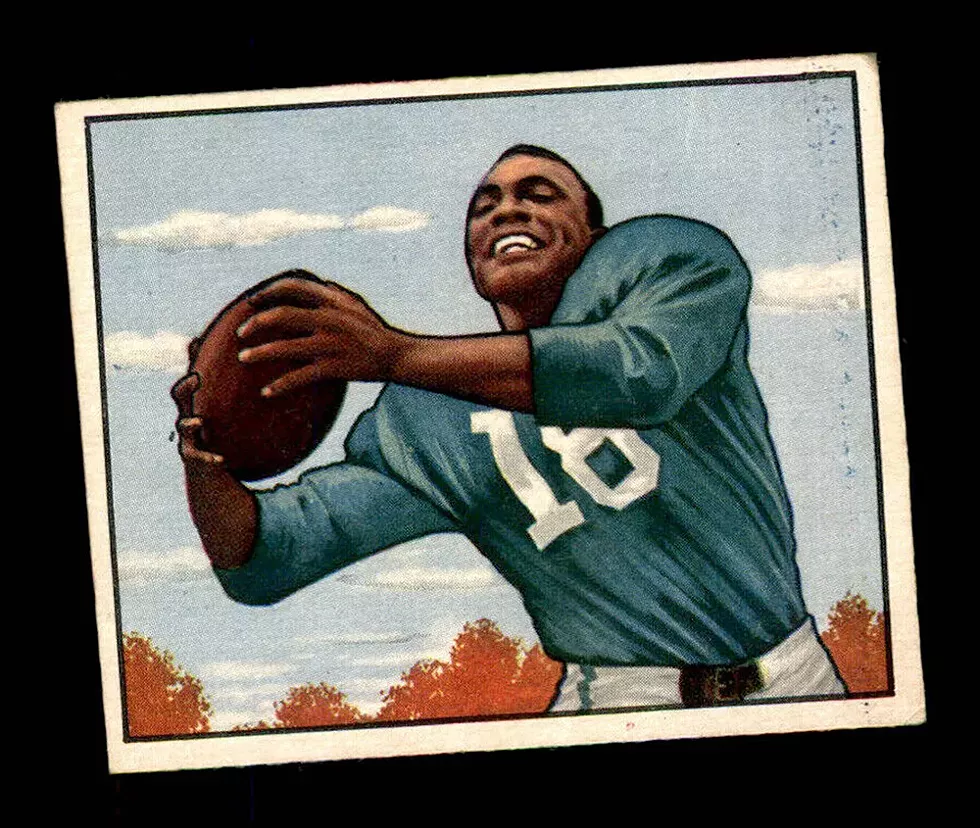

In April 1948, one of McMillan's "sepia stars" at Indiana, halfback Mel Groomes, became the first Black player to sign a contract with the Lions. Bob Mann, an end on the University of Michigan's 1947 undefeated national champions, quickly became the second. Both men, passed over in the NFL draft and signed as free agents, played the 1948 and '49 seasons with Detroit. Groomes was hampered by a broken wrist and appeared in a total of nine games before entering the air force. Mann, known for his good hands and precise routes, was a far more productive receiver, setting several team records.

In 1949, the NFL held a historic draft. For the first time, Blacks were selected, a consequence of their demonstrated excellence in the rival AAFC. The Lions picked halfback Wally Triplett, characterized by one reporter as "the Negro bundle of power from Penn State," in the 19th round. Triplett became the first Black draftee to play in the NFL. (He was not the first Black NFL draft choice, however. That honor went to Groomes's former Indiana teammate, back George Taliaferro, who was selected in an earlier round by the Chicago Bears but chose to play with the Los Angeles Dons of the AAFC.)

Over the years, Mann and Triplett offered differing accounts of their reception in the Detroit locker room. On balance, it appears that such clubhouse leaders as "Bullet Bill" Dudley and players from integrated college programs — Michigan's John Greene and Notre Dame's Gus Cifelli and John Panelli — were most open to their new Negro teammates. "I just thought he was here to make our ball club better," Dudley, a courtly Virginian, said of his introduction to Mann. "And I was all for it."

To outsiders, at least, the Lions appeared admirably progressive. There were only seven Blacks in the entire NFL in 1949, and three of them — Mann, Groomes, and Triplett — played for Detroit. There almost was a fourth. Richard Boykin, a rangy 220-pound fullback from Ohio coal country with no college experience, was signed to a contract in early 1949. Boykin came to camp, but was cut and returned to playing for the semipro Ironton Bengals.

“Bo could have ended all that. He was supposed to be Mr. Great Liberal. . . . He had a chance to be a hero, step up to the plate, but he didn’t do it.”

tweet this

However, during the 1949 preseason the Lions' "colored contingent" learned there was a limit to the club's liberalism. The team was scheduled to play an exhibition game against Philadelphia in New Orleans, a city where mixing races on the athletic field was forbidden. Before the team left Detroit, McMillan called his trio of Black players into his office. He explained that the sponsors of the game were leaving it up to him as to whether he wanted to risk the consequences of breaking the local color bar. McMillan ultimately decided that he would not risk tackling Jim Crow on his own home turf. The players could make the trip, but they would be held out of the game. Moreover, they would not be able to stay with the rest of the team at their hotel but would instead be lodged at a Black boardinghouse.

Recalling the incident in 2005, a year before his death, Mann angrily said: "Bo told us he didn't think he should be the one to break it. I thought to myself, 'Fine, that's his decision.' Bo could have ended all that. He was supposed to be Mr. Great Liberal. . . . He had a chance to be a hero, step up to the plate, but he didn't do it."

In McMillan's defense, he had a right to be worried. North or south, racial animosities occasionally spilled onto the gridiron. A few weeks after the Lions' exhibition in New Orleans, a pair of unbeaten downriver Detroit high school teams met in a showdown for the league championship. The host team, Melvindale, fielded an all-white squad. The visiting River Rouge team had seven Blacks in its starting lineup (including Howard McCants, who five years later would be one of the few Black collegians drafted by Buddy Parker). Epitaphs flew freely and, by game's end, so did fists. A riot involving several hundred fans ensued, resulting in the game being forfeited to River Rouge. Blacks complained to police of being attacked without provocation, with the injured including a middle-aged couple dragged from their car by knife-wielding whites. Four people were seriously hurt, with three of them suffering stab wounds.

Police seemed reluctant to investigate too deeply. They pointed to the teams' long rivalry and maintained the melee was fought along school lines. Local civil rights leaders were unconvinced. Coming just six years after the '43 riot, the violence was the latest reminder that the city was still a vat of racial tensions, bubbling away on slow boil.

"This was not a happy town by any means," Triplett said. "We'd just finished a race riot. Because of restrictive covenants, Blacks had to live in certain areas of town. The police department was racist. You couldn't be in certain areas at certain times." However, in many other ways, Detroit "was a beautiful town," Triplett continued. "My dad loved it when he visited from Philadelphia." Triplett fondly recalled Paradise Valley, where he spent probably too much time and money. "Man, the Black-and-Tans, everybody got along. The speakeasies would come alive at two in the morning. You could walk the street then. You'd put your hat in the back seat of a convertible, and at 6 a.m. it'd still be there."

Mann, who liked Detroit so well that he settled there after his playing days were over, experienced the same schizophrenic relationship. "It was an unusual city," he said. "It was bad in one way and great in another. The places that were available were just wonderful."

One such place was the Gotham Hotel, run by local gambling kingpin John White. The twin-towered complex of shops and rooms on Orchestra Place was one of the centers of Detroit's Black social life. It hosted Duke Ellington, Lena Horne, Billie Holiday, the Harlem Globetrotters, and other notables who couldn't stay at white hotels. Mann, a fashionably attired man with processed hair and an Errol Flynn pencil mustache, was tipped off by hotel staff whenever an attractive actress or singer checked in. "Segregation was bad," he said wryly, "but it had some good points."

In 1949, Mann enjoyed the best season yet by a Black player in the NFL. He had 66 catches, second only to Tom Fears of Los Angeles, and led all receivers with 1,014 yards, one more than Fears. A pay raise was a reasonable expectation for the man who had just set franchise records for receptions and receiving yardage. Instead, Edwin Anderson, citing the financial losses the Lions had incurred during the recently concluded war with the AAFC, wanted Mann to take a $1,500 pay cut for the 1950 season. This would have slashed his salary from $7,500 to $6,000. Mann refused to sign a contract.

Complicating negotiations was Mann's off-season sales job with Goebel Brewery, of which Anderson was president. In the summer of 1950, two long-time Goebel employees, both white, were given a distributorship whose delivery area was in a predominantly Black section of Detroit. A group called Business Sales Inc. protested that the distributorship should have gone to a Negro and organized a boycott of the beer maker. The boycott collapsed when Black bar owners and businessmen, made aware that Goebel employed far more minorities than any other brewery in town, decided not to support the activists.

Anderson believed Mann was somehow involved with Business Sales. On the day players reported to training camp in Ypsilanti, Mann lost his brewery job. Four days later, he was sent to the New York Yanks (formerly the Bulldogs). This completed the transaction that had brought Bobby Layne to Detroit.

Mann later recalled the whole unhappy episode as "just a whole lot of mess." But it was to get worse. He played only three minutes for the Yanks during the entire exhibition season. When he did get on the field, the quarterback was instructed not to throw to him. Mann was told he was "too small" and then waived out of the league — bewildering treatment for one of the NFL's top receivers.

"I must have been blackballed — it just doesn't make sense that I'm suddenly not good enough to make a single team in the league," the out-of-work end said two months into the regular season. When Mann successfully applied for unemployment compensation, Goebel Brewery appealed the decision. "While Bob is just now arriving at the conclusion that he was 'railroaded' out of the league, fans saw through the maneuver when it was made," Russ Cowans wrote at the time. "The word was probably passed along that Mann is a 'bad character' and should be shoved out of the league."

Finally, the lowly Green Bay Packers signed Mann with just one game left on the 1950 schedule. Green Bay was the league's version of Siberia — a frozen outpost filled with white folks who figured to be less than welcoming to the team's first Black player. "Green Bay was a little town, but rough," Triplett said. "They let you know how they felt." According to Mann, there were only two other Black people in all of Green Bay when he arrived — a hotel porter and a railroad cook — so he got the head coach's permission to regularly drive his Chrysler New Yorker to Chicago and Milwaukee to socialize.

Mann's closest friend on the Packers was tackle Dick Afflis, an exceptionally violent person who demonstrated little patience for those who couldn't see beyond his teammate's skin color. "I was hailing a cab in Baltimore once, but the driver wouldn't let me in," Mann recalled. "Dick opened the passenger door and pulled the guy onto the sidewalk and quickly convinced him to take me."

Mann played for the Packers until he suffered a career-ending knee injury in 1954, the same year Afflis quit the NFL to embark on a full-time wrestling career in the Detroit-Windsor area under the ring name of "Dick the Bruiser."

Many of the top Lions of the 1950s were southern whites, as were several of the coaches. They had grown up in an era of strict segregation, so their attitudes were set early in life and not easily changed. According to Triplett, "the Texans" on the squad were cool to his presence in the locker room, barely acknowledging him, though Doak Walker strived to set the correct tone. Cloyce Box, the proud grandson of a Confederate cavalryman, "was kind of reticent at first," Triplett said. "After he saw how me and Doak got along, things got better." Triplett initially had a small problem with Bobby Layne "saying things out of habit" and dropping the occasional N-bomb in casual conversation, but he considered the quarterback a friend and found him to be an equal-opportunity partier.

During most of his two seasons in Detroit, Triplett lived in a boardinghouse on the near east side. It was a lively and inviting environment for "sports" of all races and tastes. Layne was known to serve as host to visiting Black players. San Francisco end Charlie Powell recalled: "We would just get through playing and either the Lions would whip our butts or we would whip their butts, and he would say, 'Charlie, go get dressed. I'll wait for you outside your dressing room.' He would take me to the nicest clubs in Detroit, and they would roll out the carpet for him." Layne made the rounds of the Flame Show Bar, the Chesterfield Lounge, the Frolic Show Bar, and other jazz venues, "and everybody in those places knew him, too," Powell said.

Fourteen Blacks played in the NFL in 1950, with nine of them suiting up for either Cleveland or Los Angeles. The Browns and Rams met in that year's title game, as well as the next. Such success was not a coincidence, the Black press enjoyed pointing out. By 1952, every team except Washington had fielded at least one Black player since the end of the war, though, collectively, Blacks still constituted only a small fraction of the league's players.

Of those who did play, most were stars. In 1954, for example, the league's top five ground-gainers were Black. Nonetheless, a racial slur could fly out of the most unexpected mouth, said Triplett, recalling a game against San Francisco. "I hit their quarterback, Frankie Albert, out of bounds and he went into the bench. That precipitated a fight. The coach, Buck Shaw, raised hell to the official and he said, 'Don't worry, Buck, that nigger's out of the game.'"

During the '50s, club owners continued to drag their feet when it came to signing Blacks. It's believed most teams had an unspoken quota each felt it could comfortably field without upsetting local fans, sponsors, shareholders, and the perceived harmony of the locker room. During this transitional decade, coaches were guilty of "stacking" Blacks at certain positions requiring speed and brute strength, particularly end and back, so that they might eliminate themselves through competition. This allowed a team to avoid accusations of being discriminatory. Meanwhile, other positions were reserved for "brainier" whites.

Pete Waldmeir, then a young, freethinking sportswriter with The Detroit News, remembered being tutored in the early '50s about "how things go" in matters of race and sports. He was told by one unnamed baseball executive (presumably with the Tigers) that a team needed to be "smart down the middle." That meant not fielding a Black catcher, pitcher, or center fielder. Waldmeir was incredulous. "When I ran that outrageous scenario past a pro football coach," Waldmeir later wrote, "he listened intently, and then agreed. 'Nothing wrong with that,' he said. 'Why do you suppose we don't have Blacks at quarterback, center, middle guard, and safety?'"

The Tigers, the second-to-last major league team to desegregate, were widely viewed as a racist organization. Owner Walter O. Briggs was a strong-willed industrialist who made little secret of his distaste for organized labor in his factories and an integrated ball team on his diamond. Edgar Hayes of the Detroit Times said old-timers in the press box characterized the Tigers' unofficial policy as "No jiggs with Briggs."

The Lions, closely associated with the Briggs name, were considered in the Black community to be just as bigoted. Certainly Blacks felt less than welcome at Briggs Stadium, whether they were there to watch the Tigers or the Lions. Black baseball fans were seldom seen in the better seats — the field boxes and the lower-deck reserved seats between first and third base — because employees handling in-person ticket sales quietly steered them to certain "colored sections," particularly the lower-deck bleachers. According to Waldmeir, "when season ticket orders were mailed in, the addresses were checked. And orders that came from 'Black neighborhoods' were filled selectively because they didn't want to alienate white customers by seating them next to African Americans."

Throughout the 1950s, the two teams meeting in the title game each December typically were those fielding the most Blacks that particular season: Cleveland, Los Angeles, and, later in the decade, Baltimore and the New York Giants. The only consistent exceptions were the Lions, who in four championship games suited up just two Black players: Harold Turner in 1954 and John Henry Johnson in 1957.

"I don't think the coaches had anything against signing Black players," middle linebacker Joe Schmidt said in Parker's defense. "I think it was more of a case of scouting not being very sophisticated in those days. Hell, they were still drafting some guys out of magazines. Nobody was paying much attention to those small Black colleges."

Scouting being what it was back then, scrutinizing the larger out-of-state programs usually involved having a local part-time scout (typically a college coach or former player) bird-dog a particular school or conference and make recommendations. Many picks, white or Black, were selected without Parker or any of his coaches once personally setting eyes on the player. For example, Auburn halfback Dave Middleton became Detroit's top choice in the 1955 draft based solely on the recommendation of Louisiana State's head coach. A couple of years earlier, Kansas tackle Ollie Spencer inadvertently caught Parker's eye as the coach slogged through hours of film of that year's East-West Game and Senior Bowl. "So strictly from his performance in those games we drafted him — 'from the pictures,'" Parker said.

It's quaint to see the emphasis Parker placed in his 1955 book, We Play to Win!: "To demonstrate the importance of the talent-scouting operation, I'd just like to mention that National League teams spend an average of between $20,000 to $35,000 each season on scouting college players." Some of that money went for envelopes and stamps, as every year questionnaires were mailed to several hundred graduating seniors. At the end of the form, each player was asked: "Please name the five best players you have played against during the past season."

"We take these tips and then begin investigating the gridders immediately," Parker noted. With few, if any, of the questionnaires sent to players at historically Black colleges, and all of the Lions' scouts being white, it's hardly surprising that most Negro players weren't on the radar.

The Lions' scouting system was upgraded with the hiring of former Michigan halfback Bob Nussbaumer as full-time talent coordinator in 1954. Within a couple of years, the Lions were contacting 1,800 players each September, following up with phone calls to the 50 most promising prospects in late November and then telegrams to a select 15 finalists as draft day approached.

A total of 361 collegians were drafted each year by the NFL: a bonus pick selected by lottery, followed by 30 rounds of one pick by each of the 12 teams. The draft was held in January, usually in Philadelphia or New York. From 1956 through 1959, the draft was split into two parts. The first three or four rounds were held just after Thanksgiving in order to give NFL clubs a better chance to sign the top players before Canadian teams got to them. The remaining rounds were then held in January.

The record shows that Parker drafted a handful of Blacks, usually in the latter rounds as the pool of talented white prospects dwindled. In 1952, he selected Tennessee end Harold "Bulldog" Turner but lost him to military service. Turner came to camp in 1954 after spending two years in the Marines. He was sold to Cleveland during training camp, released, and subsequently re-signed with the Lions. He got into the final three games of the season, plus the championship game, replacing injured rookie back Dick Kercher on the roster. Turner's teammates voted him a half share of the title-game money.

Ray Dohn Dillon of Prairie View College was Parker's last pick in the '52 draft and the 357th choice overall. "Ray Dillon, the huge fullback ... has been impressive on occasion but on others looked like an ordinary player," Bob Latshaw wrote not long before Dillon was cut. Recalling his monthlong stint at training camp in Ypsilanti, Dillon later said that one of Parker's coaches dubbed him "Radar" for the aggressive way he shadowed Doak Walker and others on pass defense. "He said, 'Radar, you were supposed to make this team, but it's over my head right now.'"

In 1954, Parker made end Howard McCants, the former River Rouge High School star and the first Black player at Washington State, the 49th overall pick. The 6-foot-8, 230-pound high-jump champion, whose yardage-gobbling strides drew comparisons with the fading and soon-to-be-retired Cloyce Box, signed contracts with Detroit and the Toronto Argonauts.

"I intended to play with Detroit until I saw some things I didn't like," McCants said cryptically, refusing to elaborate on what those things were. That year, the Lions also drafted UCLA back Milt Davis, who was called into the army before he could try out for the team.

In 1955, the Lions selected a pair of linemen who impressed coaches and reporters at training camp. Elijah Childers, a "husky Negro tackle" from Prairie View, was described as "a poor man's Les Bingaman." But the 265-pounder was waived a week before the start of the regular season when Gil Mains returned from Canada and took his spot on the roster.

The other lineman was Walter Jenkins, a local star at Miller High and Wayne University. Quick, rugged, and a sure tackler, Jenkins was shifted from tackle to defensive end. In his first game, the 1955 season opener at Green Bay, he slammed into [Packers quarterback] Tobin Rote and caused a fumble, which Mains recovered for a touchdown. Jenkins started his second straight game at Baltimore, but two days later was waived. The Lions had acquired Los Angeles end Bob Long, and Jenkins was deemed expendable. A third Black, halfback William "Tex" Clark, had been Childers's college teammate. Clark was signed as a free agent but released the same day Childers was cut.

Perhaps the most promising of Detroit's Black draftees during Parker's tenure was Calvin Jones, the three-time All-American guard from the University of Iowa. Jones was a two-way marvel and a pioneer. He was the first African American to win the Outland Trophy, awarded annually to the top college lineman, as well as the first Black athlete and the first college player to grace the cover of Sports Illustrated. Although the Hawkeyes had a poor season in Jones's senior year, the Iowa captain still finished tenth in voting for the Heisman Trophy, a commendable achievement for a lineman of any color.

Today, Jones probably would be a first-round draft choice. In 1956, he had to wait until the ninth round, when Parker made him the 98th overall pick. Jones had already established himself as a man who demanded respect. After committing to play for Woody Hayes at Ohio State, he impulsively joined two Black childhood friends in enrolling at Iowa.

"I'll tell you why I came out here," he explained at the time. "They treated me like a white man, and I like it here. I'm going to stay."

The Canadian leagues, which fielded their first Black American player in 1946, were an attractive alternative for many Black collegiate stars. John Henry Johnson, for example, played his first season out of Arizona State for the Calgary Stampeders before switching to the NFL. Jones, swayed by the higher pay and more hospitable environment many Blacks found "up north," snubbed Detroit and instead signed with the Winnipeg Blue Bombers. His career ended tragically when he was killed in an airplane crash after his rookie season.

In the view of Milt Davis, Jones's decision to forgo Detroit directly affected his own chances to make that year's Lions squad. Davis, invited to camp after spending two years in the army, was put on waivers after suiting up for the first two regular-season games in 1956, neither of which he appeared in. Davis claimed he was victimized by an unwritten team policy. "We don't have a Black teammate for you to go on road trips, therefore you can't stay on our team," he recalled Parker telling him.

"That's one of those slaps in the face," Davis said. "It hurt considerably, but I'd been hurt so many times, that was minor." The following year, he had a successful tryout with Baltimore and signed with the Colts as a free agent. As a 28-year-old rookie, "Pops" Davis picked off 10 passes in 1957, tying Jack Christiansen for the league lead.

Davis retired after just four NFL seasons with Baltimore, having twice led the league in interceptions while helping the Colts win the last two championships of the 1950s. Part of the reason he left the game in his prime was money (he was making less than his white counterparts) and part of it was his desire to finish his degree (he was working on a doctorate in education). The decisive factor was his desire for simple self-respect. The All-Pro cornerback, army veteran, and doctoral candidate was tired of being turned away at whites-only restaurants and theaters, being directed to the "colored taxi stand," and sleeping in rundown boardinghouses in the "Negro section" of whatever city his team happened to be visiting.

In Dallas, the community that so warmly embraced Doak Walker, Bobby Layne, and Parker, Black players routinely encountered hostility and humiliation. Seared into Davis's memory was checking into a rundown Dallas boardinghouse, which the manager insisted was air-conditioned. "He goes to this room and opens the door, and he had a fan on a chair in front of the open window," Davis said. "I thought the ceiling was gray; it was all mosquitos up there."

When Buddy Parker moved on to Pittsburgh in 1957, he inherited a team with two Black veteran players — defensive back Henry Ford and tackle Willie McClung — and one new Black coach, Lowell Perry. By the following season, Ford had been cut, McClung traded to Cleveland, and Perry reassigned as a scout. The shake-up could have been the usual personnel turnover, or it could have been something else.

Ford always maintained that he was cut and subsequently blacklisted because coaches learned he was dating a white woman — a major societal taboo in the '50s. Ford was starting his third NFL season when Parker took over. He was coming off a solid year as a two-way back in 1956 and had just enjoyed a fine preseason effort against the Lions in September 1957, Parker's first game as Pittsburgh's new coach. "I was playing offense and defense, and I thought I really had a hell of a day," Ford told Andy Piascik in Gridiron Gauntlet.

But when the team returned to practice the following Tuesday, Ford wasn't part of the regular offensive, defensive, or special teams drills. The same thing happened on Wednesday. He figured some rookies were getting a final look-over.

"Thursday came, same thing. Friday, same thing. On Saturday I was home looking forward to the game on Sunday, getting myself prepared, getting my clothes packed for the trip and everything, and I get a phone call from the business manager. Not the head coach or even any other coach, but the business manager ... and he says, 'That's it.' I said, 'What do you mean, that's it.' He said, 'They told me to tell you that's it and they'll take care of you when we get back from the game,' and he hung up. And that's how I was cut, right after I had played a hell of a game against the Detroit Lions."

Ford, who suspected the team was listening in on his phone calls, was devastated. Suddenly no club in the NFL was interested in him. The woman he was seeing became his wife of many years, an interracial marriage that survived the expected barrage of ugly comments and snubs, some coming from members of their own families. Although Ford later prospered in the corporate world and as a high school coach, "Being kicked off the team for something that had nothing to do with football or how I played the game caused me a lot of emotional trauma," he said.

In the early '60s, Parker's Steelers included a handful of Black players, notably John Henry Johnson, guard John Nisby, tackle Gene "Big Daddy" Lipscomb, and defensive backs Brady Keys and Johnny Sample. Sample was offended by what he saw as Parker's patronizing treatment of an older Black man named Wallace "Bootsy" Lewis. Parker considered Lewis, a craps-shooting handyman he'd first met at Centenary College and later discovered operating a shoe-shine stand in Los Angeles, his "good luck" charm. Parker invited Lewis to sit on the Detroit bench whenever the Lions were playing the Rams. Later he brought Lewis to Pittsburgh to act as his personal valet.

"Bootsy would wake Buddy up in the morning, shine his shoes, get him coffee, and so on, for which he was paid next to nothing and treated like a dog," Sample said. "John Henry Johnson had to drive Bootsy from practice at South Park, about an hour outside of Pittsburgh, to where he stayed in the city, because Parker wouldn't give him a ride. In fact, John Henry bought his lunch because Bootsy never had any money."

It was unavoidable that Sample's brash style would get under Parker's skin. In 1961, they nearly came to blows when the coach brushed aside Sample's demand for a pay raise by saying, "I know you had a great year, Sample. But Black athletes just don't deserve that kind of money, and I won't pay it." Parker was hardly alone among old-school NFL types in believing that, on the whole, Black players were intellectually inferior to their white counterparts, and thus worth less money.

Buster Ramsey was on Parker's staff in Detroit and Pittsburgh. In retirement, he was asked by sportswriter Dan Daly why Buddy didn't have more Blacks on his teams. "I ain't gonna tell you," Ramsey said. "You can figure it out." Given the unenlightened environment of Parker's formative years — Texas in the 1920s and the NFL in the '30s and '40s — perhaps the most charitable characterization of the coach is that he was a product of his times. But those times were changing.

Throughout the 1950s and into the '60s, Jim Crow practices in much of the South continued to restrict the mixing of races in many aspects of everyday life. It was a sign of the times that in August 1957, when John Henry Johnson didn't travel with the Lions to Birmingham, Alabama, for an exhibition game, his treatment elicited no outcry or commentary in Detroit's three daily papers. It was business as usual. That September, President Eisenhower sent the 101st Airborne to Little Rock, Arkansas, to forcibly integrate Central High School. The tense showdown between federal and state authorities played out on television screens across the country and became another landmark victory in the burgeoning civil rights movement. Johnson himself noted some years later that, as bad as race relations were at the time, his predecessors had endured worse. "Some of the guys who came before I did — the problems and discrimination they had to go through — it was rough," he said. "When I started playing, that kind of thing was sort of on its way out. People were starting to accept the fact that we were good football players and we could contribute to the game."

Such contributions were showcased at the 1958 College All-Star Game, when Black stars played key roles in the collegians' shocking 35–19 whipping of the reigning NFL champion Lions. Fans saw Michigan halfback Jim Pace break off the game's most electrifying run, Washington cornerback Jim Jones pick off three Bobby Layne passes, and Bobby Mitchell of Illinois spend the evening "making monkeys" out of Detroit's famed secondary.

"Actually both teams were liberally sprinkled with Negro players; and as has been the custom in recent years they were simply taken for granted," Howard Gould wrote in the Chicago Defender. To Gould, the prosy reaction to the growing presence of Blacks in such a high-profile sporting event was a solid indicator of progress. When the Chicago Tribune started the charity game a quarter century earlier, "the state of race relations was such that a Negro student could not play football or basketball at the University of Illinois," he continued.

"Friday night one of the outstanding stars was Bobby Mitchell from that school. Undoubtedly there were fans who noted that Mitchell comes from Arkansas, and who may have commented that he would be denied the right of playing football at Central High in Little Rock. The point of comparison rests in the inevitability of the fact that change will come to Little Rock and similar places, just as it did to Champaign, Illinois. Another comparison may be made of the Detroit Lions of Friday night as against the same team years ago. There was a time when astute fans would have laughed at the idea that a player from a small Negro college might play for the pros, but along with Danny Lewis and Johnson Henry Johnson, Detroit fielded a man from Kentucky State [halfback Henry Herzog]. These comparisons can best be understood by the older adults. Watching a spectacle like the All-Star Game they can think back over the years, and remembering the past from a race relations point of view, recognize the fact that the youngsters of today don't see as many racial barriers as they had to in the past."

While the country was then, and still remains, far from color-blind, 1950s activism set the stage for monumental change, with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 remaking American society. Long before that, it was clear to all but the most delusional obstructionists that Black athletes were here to stay.

In 1960, rookie Roger Brown, a huge tackle drafted out of Maryland Eastern Shore, joined the Detroit lineup. That same year, the Lions traded for veteran defensive back Dick "Night Train" Lane, a future Hall-of-Famer feared for his necktie tackles, and acquired Willie McClung from Cleveland. With halfback Danny Lewis, who was drafted out of Wisconsin in 1958, this gave the Lions four Black players on the roster for the first time. By 1960, a total of 143 African Americans had played in the NFL since the color barrier was permanently breached in 1946, including 10 with Detroit. The league was now roughly 12 percent Black, a percentage that would steadily climb over the coming years.

Just as the NFL turned a corner in fielding Blacks, the American Football League (AFL) started play in 1960 in eight cities, giving players of all colors another option for their services. College stars often found themselves drafted by both leagues. Many Black draft choices — seeking a better opportunity, higher wages, or a more tolerant atmosphere — ignored the established NFL and signed with the AFL, just as others had earlier opted for the Canadian leagues. The Washington Redskins, the last all-white holdout in professional football, were forced to desegregate in 1962 at the risk of losing the right to play in their municipally funded stadium. Meanwhile, the civil rights movement pulled along a new generation unafraid of being militant. In 1965, Black players in New Orleans for the AFL All-Star Game forced the league to move the contest to Houston because of the city's blatant discrimination.

The growing number of integrated major college programs meant a deeper pool of talent to choose from on draft day. The Lions enlisted local high school coaching legend Will Robinson to help scout Black prospects. Such players as Bobby Thompson, Ernie Clark, Jerry Rush, Mel Farr, Earl McCullouch, Larry Walton, Altie Taylor, and future Hall-of-Famers Lem Barney and Charlie Sanders were signed by Detroit during the 1960s. They were in the vanguard of a remarkable transformation as the NFL and AFL merged into one league in 1970. Within the span of a couple of generations, the complexion of professional football changed from wholly white to majority Black on the playing field.

Presently, roughly 70 percent of all NFLers are African American. Although integrating the coaching and management ranks continues at a much slower pace, in 2014 the Lions hired Jim Caldwell as the club's first Black head coach, an event that passed with scant commentary about race. Today, Detroit fans cannot imagine a team history that does not include such Black standouts as Billy Sims, Al "Bubba" Baker, Barry Sanders, Herman Moore, and Calvin Johnson.

Among the players themselves, little thought is given to the pioneers who took on an intimidating adversary named Jim Crow. "I don't think these young Black players in the game today have any idea what we had to go through," John Henry Johnson once reflected. "They might have heard a little bit, but when they came in, we had their beds made for them and it was a lot easier."

Bob Mann returned to Detroit after leaving the NFL, working in real estate and earning a law degree. When the Lions inaugurated their new domed stadium, Ford Field, in 2002, he was invited to serve as honorary captain. One of the team's stars, nose tackle Shaun Rogers, was impressed by the trim and distinguished-looking septuagenarian.

"Man, I'm glad to meet you," Rogers said. "We don't know much about you guys." To which Mann replied: "I know you don't."

Excerpted from When Lions Were Kings: The Detroit Lions and the Fabulous Fifties by Richard Bak, available now from Painted Turtle, Wayne State University Press. It is reprinted here with permission.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.