Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy

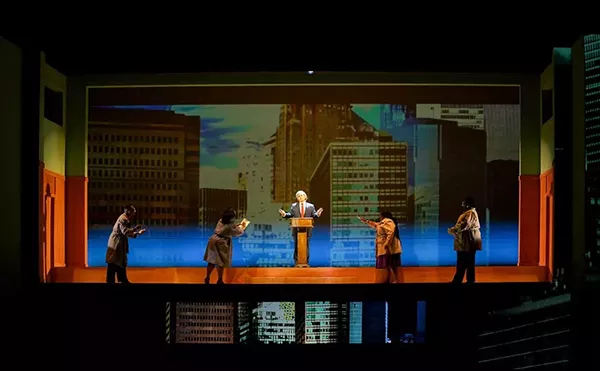

Quiet desperation - Gary Oldman in a surprisingly humane portrait of folks regularly engaging in acts of inhumanity

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy

B+

Gary Oldman has earned such a reputation for his explosive, scenery-chewing career that when the now-53-year-old actor quiets down and turns inward, critics herald his performance as revelatory. But while his poised approach to George Smiley in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy may seem like a tour de force of restraint, one only has to consider his turns as Commissioner Gordon in The Dark Knight or Sirius Black in the Harry Potter films to see that the British actor has more than bombast up his sleeve. Contextually, the roles couldn't be further apart, but Oldman brings a stoic sense of watchful melancholy and tired decency to each, portraying men who may be physically past their prime but who are smart and talented enough to remain in the game. He expertly exploits the subtle wrinkles and tics in his ever-expressive face to deliver deceptively intimate performances.

In this efficiently condensed adaptation of John le Carré's seminal spy novel, directed by Tomas Alfredson (Let the Right One In), Oldham slips into and gets under the skin of the aging and inscrutable Smiley, an agent who's been brought out of forced retirement to help MI6 (sardonically dubbed the "circus" by those on the inside) uncover a Russian mole. Smiley's old boss, known only as "Control" (John Heard), has died, leaving behind a list of code-named suspects (thus the title). Smiley even finds himself on the list, a fact that doesn't surprise him in the least. The world of espionage brings with it an endless cycle of distrust. Still, Smiley has a relationship with each of the suspects, and must enlist a nervous but loyal young agent (Sherlock's Benedict Cumberbatch) to help him root out the culprit. From Hungarian defectors to Soviet double agents to internal rivalries and failed relationships, Smiley untangles an incestuous skein of egos, operations and deceptions, and discovers that even he has a tragically personal blind spot.

Alfredson's icy and austere direction brings an effective detachment to le Carré's Cold War plot. His meticulous, no-affect approach is perfectly suited to capturing the isolating atmosphere and moral murkiness that permeates Smiley's world. Unfortunately, as drama, Tinker struggles to make an impact. The search for a Soviet mole is, ostensibly, a whodunnit, but Alfredson and his screenwriters (Bridget O'Connor and Peter Straughan) do little to engage us in the hunt. The final revelation (which is hardly a surprise) comes almost as an afterthought. The characters and tone are compelling but, aside from a tense scene where Cumberbatch must swipe documents under the noses of his superiors, the movie generates few actual thrills.

Tinker is far better as a slow-burning study in blank-faced paranoia. Upright and uptight, the British spy community is depicted as sad and lonely, filled with despairing individuals who have sacrificed their personal lives for the alienating obsessions of their profession. It's a surprisingly humane portrait of people who regularly engage in acts of inhumanity. Their sallow complexions and drab, claustrophobic surroundings only underline the casual amorality that has permeated their lives. From the movie's opening scene — a failed mission that leaves a nursing mother dead and an agent (Mark Strong) shot in the back — it's clear that emotion and regret are luxuries that have no place in a world infected by deceit, corruption and subterfuge. For all Smiley's understated savvy and smarts, his is a life marked by illusory relationships, shifting ethics, and an endless cycle of zero-sum plotting and counterplotting.

Alfredson finds small opportunities to ironically comment on the grim absurdity of the spook's existence — the best of which is a flashback to a depressing company Christmas party. Crowded into MI6's functionally cluttered office space, workmates and spouses desperately and drunkenly cheer the holidays even as they betray their marriages, and, as the future reveals, each other.

Disappointment and distrust become the foundation for every interaction in Tinker and it's hard not to connect the tired corruption that defined the espionage efforts of the 1970s to the political cynicism and dysfunction of today. Alfredson makes clear that the wages of sin are indeed death, if not of the body then certainly of the soul. —Jeff Meyers