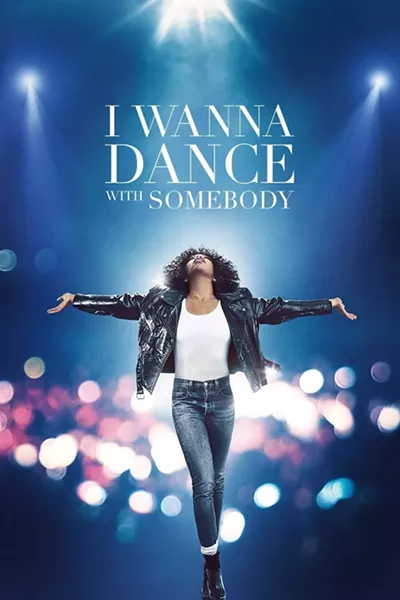

The limits of ‘Whitney Houston: I Wanna Dance With Somebody’

Biopic struggles to capture what made the star so compelling

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

The primary accomplishment Whitney Houston: I Wanna Dance With Somebody makes is a successful argument that we must abandon the idea that movie biopics are the best vehicles to tell someone’s life story. Whose life can successfully fit into 90 minutes, 120 minutes, or even 180 minutes? And to think one can manage to tell the life story of someone as enigmatic and complicated as Whitney Houston’s in one movie is ludicrous. But try they did, and the result is a film that simultaneously doesn’t tell you enough about Nippy but tells you so much about what we already know — and it still manages to do only the CliffsNotes. Out of all the pop stars we have had and lost, her legacy is possibly the most intertwined with tarnish and sadness. Of her contemporaries, her career is the one most linked with scandal and a hint of not just loss but failure. Given that, the film is a course correction of sorts, but even in that regard it comes up short in some ways.

Oddly, despite the highlights, I’m not sure the film did a great job of showing you just how huge Houston was. She, not Madonna, left the ’80s as the best-selling woman artist of that decade; she, not Madonna or Mariah, managed to become a legit movie star; she is a woman whose career at one time Madonna envied to the point that while, feeling sorry for herself, she called Whitney “horribly mediocre” and then compared herself to Black people while completely unironically not recognizing the hoops Whitney had to go through to be who she was — demands not put on Madonna because she is white. And to be clear, while some of the material was mediocre and even generic, Whitney never was — see her singing “Saving All My Love for You” in Japan; the things she does with her voice is astounding, and then you realize she is just standing there. She was a Black American woman who flew too high, was too perfect — so when she proved to be too human, the fall was steep indeed. The paparazzi that hounded her became more ravenous, the light became even brighter and more blinding.

Say the name “Whitney Houston” and for many, drugs come up rather quickly, followed by sound bites: “show me the receipt,” or the ever-popular “crack is whack.” Left out is that she also mentions crack being cheap, which highlighted a savvy intelligence Whitney had; every Black person knows a dog whistle when it’s blown. Yes, she said crack is whack, but she was a Black woman struggling, coming off reports that she had died, the ridicule of millions, and sitting across from a white woman who was about to ask her about crack — a drug with racial and economic connotations. She may have not been ready to be publicly honest but she was also strong enough to not allow people to reduce her to a racist stereotype or punchline. I honestly can’t think of too many celebrities who the media and the world has been harsher to. Prince, Judy, Janis, Kurt, and others all struggled with addiction, but few of them have been, if not reduced to, then so intimately linked with their struggles. Few were so publicly hounded and ridiculed while they were struggling. Imagine being a person struggling with addiction, turning on the television, and you see people laugh at you. Imagine paying a price of being considered a sellout only to be abandoned by the very people you allegedly sold out for. (There is a way in popular culture that Whitney Houston’s struggles have been linked to Black people — we didn’t love her enough; we booed her at the Soul Train Music Awards; we derided her music. What is left out is that we stayed. We showed up to watch her exhale, we witnessed her usher in the new generation of Pop-R&B stars; we caught the spirit with her; we were with her when she said it wasn’t right but it would be okay, we were there before the Thunderpuss remix — but that is often left out of the discussion, as is white audiences’ abandonment of Whitney Houston once she was no longer perfect.)

The problem is we still have to imagine what the emotional contours of this woman were because instead of a film using imagination to explore the interiority of one of the most important artists of the last century, we got a highlights reel due to the constraints of time and convention. To tell the story of someone like Whitney Houston what is beyond the scope of one movie; what’s needed is the time and space a limited series provides. It could easily be arranged by decade, but I’d lean toward centering around certain eras in her life and career.

The saving grace of the film was Naomi Ackie’s performance, especially when she’s singing home at the end. I always believed that Whitney was aware of what happened to her voice and that, more than anything, is what broke her. So when they showed that scene — her wanting to go back, but realizing she can’t — that was devastating. The loss of her voice just feels so cruel. This is the power of imagination. The best parts of the film are the moments when the creators had to rely upon their imagination of what Whitney’s life was like: her love for Robyn Crawford and their relationship; her miscarriage; her final moments.

But as good as Ackie was, the final moments of the film for anyone who has seen the 1994 American Music Awards love medley only highlights the distance between her and Whitney, which is to say the distance between us mere mortals and the supernova that was Whitney Houston. I understand the urge and desire; the entire film builds to it. It was very Lady Sings the Blues and showy, but what was needed was the What’s Love Got to Do With It? approach where the film, a Tina Turner biopic, and the brilliant Angela Bassett cede the remaining space and time to the actual star. It should have shown Whitney being Whitney, performing the medley herself: a simple black dress, a french bun ’90s style, her entire air evoking opera, fitting as she slides into “I Loves You Porgy,” then launches into “And I Am Telling You,” and finishes with “I Have Nothing,” sweat on her face, but her eyes — have you ever looked at Whitney Houston’s eyes as she finishes a song? Her eyes say it all: that she was doing exactly what she was meant to do in this world. Try singing along with her in the way she does, giving it everything you have. It is exhausting. And she made it look easy and feel like nothing else in the world existed for those 10 minutes but her; she made the world stop by just standing in front of the mic and opening her mouth. This, somehow, was what the movie missed; Whitney Houston was not just a pop star, she was a miracle.

Coming soon: Metro Times Daily newsletter. We’ll send you a handful of interesting Detroit stories every morning. Subscribe now to not miss a thing.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter