Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

"See more magic" is the command leveled at an early victim in Mike Flanagan’s new Shining sequel Doctor Sleep, one which could as easily be directed to its viewers. "Magic" and sometimes "tricks" are the words used to describe "shining" and the other more violent powers that appear in Doctor Sleep’s expanded world, which unspools over a wide range of American locales, few of which feel aesthetically specific or remotely personalized.

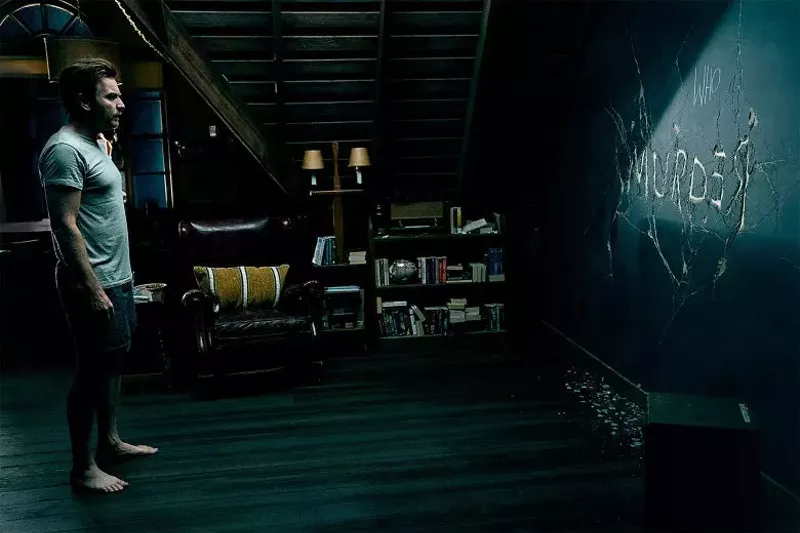

While no one should expect to see spaces photographed that rival the original’s Overlook Hotel in its ruddy grandeur or burnt palette, it’s tough not to be struck by Sleep’s drab exteriors and magazine-ready interiors, or writer-director Flanagan’s bathing of the entire film in flat, even light. Like most everything in The Shining, its architecture served as a trippy but persistent metaphor of what haunted its characters’ minds and lives. Did the Overlook exacerbate the Torrance family’s trauma — and Jack’s alcoholism — or did they bring its ghosts there with them? Its chicken-and-egg supernatural (or psychological?) vagaries stew together in a productive and classically gothic manner, establishing a blurred line between the haunting force of personal trauma and the external threat of actual ghosts. Whether the specters the Torrances encounter come from within their minds or the cursed place in which they reside doesn’t much matter — those two realities are interchangeable, the horrors they encounter made equally concrete in either case. Whatever way one sees the world — with distance or emotional intimacy, skepticism or troubled faith — The Shining likely makes a space for it: a ghost story bound up in generations of psychic trauma, it’s a flexible and living text. Likewise, Danny’s ability to "shine" scans as a way of witnessing the world with supernatural clarity. His visions and aural windows into others’ psyches, local history, and traumas old and new haunt just as the truth does. In just the way real insight shows us not just something new but the gaps between all that we know, Danny’s vision leaves him hurt and open, forced to reckon with all the mysteries of the world he has yet to understand. It’s in resistance to these truths that Jack Torrance turns to alcohol as "medicine," and which his grown-up son has turned to in this film.

And so "magic" as the word for all this seems a little bit flip, especially coming from Sleep’s top-hatted villainess Rose (Rebecca Ferguson), a haute-camp modern vampire (in essence if not description) straight out of True Blood. Unlike most in literature, she feeds off life-force (here "steam") rather than blood, vapors found mostly in people like Danny Torrance, bearers of potent powers that Rose and her long-lived vagabond gang can smell. On finding these people (they’re often children), they extract their life through inflicting pain. Existential sadists by their very nature (with strong echoes of the Mansons), Rose and her cohort hurt others both for a potent, orgiastic fix and to survive centuries past the rest of us.

Before long, these unquestionably evil attacks draw the attention of Abra Stone (Kyliegh Curran), a powerful teenager who shines herself — and so psychically feels the pain of the gang’s recent victims. She responds by seeking out Dan (formerly Danny) Torrance, played by a perfectly fine Ewan McGregor, to help combat the threat they pose. Middle-aged and still reeling, it seems, from the events of the first film and his father’s legacy (Dan, too, is an alcoholic), he buses from one New England town to another to avoid the fallout from his drunken brawls. He settles as the movie progresses in a small New Hampshire town, where he joins an AA group and finds a job, approaching a sense of peace which Abra disrupts by asking him for help.

From here, things are utterly predictable in terms of story. Doctor Sleep upsets more by confirming existing fears about the industry than arousing any new ones, moving in terms of plot in much the way a superhero story might — and with little control of its tone. As in those, a few virtuous, powerful individuals (Dan and Abra) join to fight some malevolent ones (Rose and gang). In doing so, they work to protect the innocent while overcoming their (here Dan’s) own demons, and — as in Star Wars — establishing a successive chain of mentor-student relationships complete with visions of past mentors. As the story moves, nods are given to history; motifs and scenes from The Shining (fades, overhead shots) are employed decoratively, sapped of meaning and of splendor — just as they were in Ready Player One. In a script-handbook approach to climax, Dan — eventually reaching the Overlook — is forced to confront the legacy of his dad as well as Rose in multiple and ham-fisted fashions. Abra’s youthful state and heightened power projects throughout the film ahead into the future, suggesting a threatened but hoped-for air of promise. Their powers, meanwhile, are cartoonishly expanded, broadened into psychic abilities that can move objects as large as cars.

So "shining," the haunting vision that largely suggested a way of seeing the world in the first film, is here recast as a superpower — and sapped of its emotional resonance. Its bearers seem less traumatized by horror than they do occasionally spooked, a minor inconvenience — mostly shining in Doctor Sleep works as a search engine, offering literal answers to our world’s big questions, granting assurances about life, death, and the beyond. (For a while, Dan’s job is even working at a hospice, comforting people as they die with promises of the infinite — he may as well have become a priest.) If The Shining persists, like so much stuff, because it asks hard questions and confronts ugly realities while fomenting a kind of deep-felt, searching ambiguity, then Doctor Sleep may perish for its AA-indebted belief that good works can save us, that good and evil are simply parsed, and that what viewers really need is another franchise.

For filmgoers wanting to see work imbued with a sense of mystery instead of this pat magic, they may have worse luck looking forward than they will back — at least if they seek it in Hollywood. Works like this, suggesting a broad cosmic logic in which things happen for a reason, that the good die last, and that our best futures are plainly ahead of us, fly in the face of the world we know without any sense of questioning or imagination. In place of what Doctor Sleep puts its condescending, blinded faith in, I sympathize with Jack, and Dan — or Danny — I’d rather cling to drink or ghosts.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.