Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

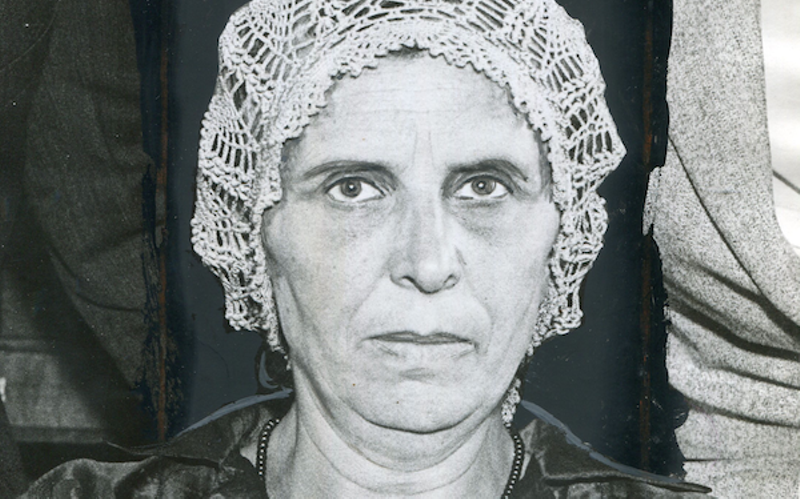

Photo courtesy Karen Dybis

Rose Veres

The book, which came out in time for Halloween, begins with the feel of a spooky true crime thriller. But as it moves forward, it makes its case that the real culprits of this caper were the ambitious judges and prosecutors and byline-seeking newswriters. The victim was the poor immigrant, a single mother who spoke little, if any, English, as well as her son. They were finally released after more than 15 years in prison.

The Veres' vindication came so long after the lurid headlines that, to this day, Detroiters still refer to her as “the witch of Delray” and a “serial killer.” The more Dybis looked into the case, the more that got under her skin. Dybis said she kept putting the project off “because I've been writing these quirky, cutesy books, making it hard to shift gears.” Detroiters should be grateful she finally got to it. Not only is it an unusual true crime tale, it casts dozens of sideways glances at the injustices of Detroit's "golden age," and has lessons for us today.

Courtesy photo

Karen Dybis

Karen Dybis: A colleague of mine did this article on a tour at Woodmere Cemetery. One of the tour guides pointed out Rose and said, “There's Rose Veres' grave. She's a female serial killer.” So that wound up in the article, and a friend of mine who knows I was doing these local history books sent me a note and asked, “If this woman is a serial killer, why is there so little written about her?”

MT: You heard some really tall tales about her, right?

Dybis: I've heard everything from she cut people up and put them into meat pies to she poisoned their wine to even that she was really a witch.

MT: Instead, your book finds that what seemed like an open-and-shut case of a cruel and wicked woman actually becomes this lengthy saga full of legal twists and turns.

Dybis: Yeah. I've been interviewed about the book on some paranormal podcasts, and their first question is often, “So she was a witch and her son was a warlock?” And I’m like, no. She’s not a witch. The book isn't scary. There are no bloody descriptions of gore and violence. Rose was just this Hungarian immigrant who didn’t know the legal system. And she had a sucky first attorney, then got lucky with a better second attorney. It’s more a legal thriller, where you go back and re-create the situation and try to unravel this thing. If I could set any of that straight, I was all in, and so the story got me, and I just kind of ran with it from there.

MT: But how do you come up with fresh information about a case that's 80-odd years old?

Dybis: I got really lucky. I had agreed to do the book already and then I stumbled onto all this great material in the Recorder's Court records at the Archives of Michigan that allowed me to write a book that's never been written before. You can go through this humongous pile of trial transcripts and affidavits and start piecing together what happened.

MT: How do you deal with the challenge of bringing long-dead people to life in a vivid story?

Dybis: You need to have archival material to kind of feed it — personal letters and some correspondence and emotional things – that might draw in your audience. Once I found the legal documents, I could take the newspaper accounts, which were really biased and out-there in terms of really believing she's a witch, and offset it with other stuff. And Detroit journalist Vera Brown wrote incredibly. I mean just big, beautiful writing, with physical descriptions in her articles. There’s always that critique that women shouldn’t be described, what they're wearing and what their hair looked like. A lot of people didn’t do that even back then. So I appreciated that there was some of that out there, and I thought, “I've got it all.”

Photo courtesy Karen Dybis

Rose Veres' grave in Woodmere Cemetery, Detroit.

MT: I noticed that one of the antagonists in your story has a surprising reversal of fortune and actually comes clean and decides to help Rose. What luck to have a character who actually is changed by the story, just like in a novel.

Dybis: The nonfiction authors that I love have explained that you've got to have people who grow and change. So it got even better when I was able to figure out that the guy who prosecuted Rose and her son was the one that actually helped get them out. When people look back and have remorse, you want to give them that credit, that at least they figured it out at some point in their life, and that redeems them. I even like that at one point in Rose’s second trial, the one lady who had testified against her is like, “Nope! I’m done. I’m not saying a word. I can’t say this a second time because maybe I don’t believe it now.” Maybe there was collusion in 1931 and there wasn’t in 1945. I can’t go back into their brains, but I think the judges were probably telling them what to say. That kind of stuff happened. And now we can look back on it and say that we can’t do that ever again.

MT: I also love the way characters that are obscure today but were well-known then keep cropping up in this story. I mean, Judge Jeffries, Sen. Homer Ferguson, Judge Scallen, Vera Brown. They all have their role to play.

Dybis: I’d never been able to do that before as a writer. I get how to write a good kicker and I get how to write a “nut graph,” but I didn’t know how to give these little gems to the reader all through the book. And now I do. These are larger-than-life people and events. I get to throw in the '43 riot or the urban renewal that led to them demoing Black Bottom. Like, I could sneak all these little things in for the reader, and that made it fun and different. I’m not a big, spooky, religious person … but I did feel like people kept inserting themselves in the story and they wanted to be in there. Like Vera Brown — I think she’s really pissed-off that she’s been forgotten in this town, and then she kind of put herself in there and was so perfect. She symbolized the journalism that was going on at the time.

MT: Particularly interesting is another especially strong female character, a crusading attorney.

Dybis: I could not love Alean Clutts more, because she is completely unknown and such an anomaly for the times even. To get a divorce in the '20s and go on to become a lawyer in her 40s … that’s unusual to some degree even today. And she goes on to kind of settle these scores, almost like she’s flamethrowing through the legal system. She looked around and said, “I can do better than you, boys and I’m going to fix this.” She was so unusual that she just delighted me.

MT: And she presents an excellent counterpoint to some of the excesses of the “old boys network” of the justice system and the yellow journalism of the time.

Dybis: You have to have a couple redeeming characters, some good, genuinely warm-hearted … I don’t know what to call them … saviors? A lot of other people just sat in jail, because no one came to vindicate them. It reminds me of all these Innocence Project cases that get people out of jail now. To prep for writing, I started listening to the Innocence Project’s podcast, Wrongful Conviction. It just would blow me away every week listening to it. And these are guys in 2017 versus 1931, so nothing much changes. It’s crazy. This is a story for all of us. For lack of a better situation, we’re all going to jail, I hate to tell you. So it’s a testament to Alean Clutts that she had the patience and the willingness to help Rose. I mean, I think that’s how half these Innocence Project cases go down is somebody’s crazy enough to give somebody a second chance.

MT: It's also important to consider all the nativism and xenophobia at the time that played into her prosecution. I mean, this is barely a decade after the Palmer Raids, back when Europeans were thrown out of country as Communists and anarchists. And other interests probably benefitted from this demonized Hungarian immigrant occupying the headlines.

Dybis: That was it: Other people benefited from her situation in so many ways. The ambitious assistant prosecutor Duncan McCrea is looking to become a judge, and Harry S. Toy has just been elected and he wants to make sure that the public sees him as cracking down hard on crime. All these people got something out of it, except for the two that were supposed to be innocent until proven guilty. When you start looking at the grander context of these stories and where this sit in American history and then Michigan and local history, it’s mind-numbing. It’s a bit scary, like, there but for the grace of god go all of us.

MT: Do you ever get that sneaking feeling that you’re speaking on behalf of somebody who's long dead?

Karen: Yeah. It’s nice to tell the story of guys who make potato chips and all that. But this was a real chance to fix a wrong in some ways. Like, I hate that people named a drink after her called the Witch of Delray. That bugs the crap out of me. That’s not right. She's just this poor woman, and I hate that she’s on cemetery tours as a serial killer. Maybe people will think twice about it and tell her true story. It’s out there now. They can make up their own mind.