Made-in-Detroit ‘Mad’ documentary is no joke

In development since 2008, a film about the beloved satirical magazine makes its local premiere

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

There’s an inherent tension at being impatient with the state of the world that is found at the core of the creative arts and, especially, satire. It is also found in a Pleasant Ridge filmmaker’s willingness to jump in with both feet to tell the tale of the culture-changing humor magazine, Mad.

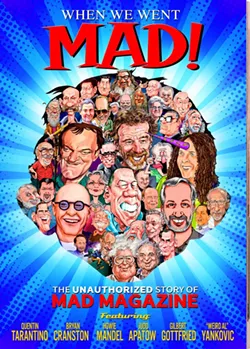

While working a day job in broadcast television production covering Detroit’s professional sports teams, Alan Bernstein felt drawn to telling this story because of the impact the subject had on his life. “[Mad] grabbed me early on and it refused to loosen its grip,” Bernstein says about the genesis of his new feature documentary When We Went Mad: The Unauthorized History of Mad Magazine, which is set for a local premiere in Detroit.

Starting the effort out of his own pocket with little crew or equipment, Bernstein would find nights, weekends, and years of his life dedicated to this personal passion of a production which he launched in 2008 for one simple reason — no one else had done it yet.

“I kept waiting for someone better than me to come along and make a documentary on Mad, which I always thought was very worthy of being told since it is such an American icon,” he says. “I kept reading about Mad artists and writers who were passing away throughout the years, and it finally just got to the point where if it’s going to happen, I’m going to do it. And that was it. I’ll figure it out later.”

How America went Mad

Once upon a time, not too long ago, poking fun at politicians, priests, or other pillars of society was definitely no laughing matter. It was a time when Congress was holding hearings to determine who was “un-American” as a way to root out “communists” and other subversives. It was a time sold to Americans that the best way to structure their lives would be for the husband to go to work, the wife to stay home, and the kids were to be ever obedient growing up in suburbs with perfectly manicured lawns protected behind white picket fences. It was a time so mythologized it has become spank bank fodder for many of the current crop of conservative politicians.

Welcome to the early 1950s.

While the image was one of a clean, neat, and orderly society, there was a problem — juvenile delinquency. Given the timeline, the armchair historian might quickly jump to rock ’n’ roll music as the cause. But that revolutionary new noise wouldn’t shake world culture until Elvis landed his co-opted version of the Black musical art form on the charts in 1956. No, in 1954, the plague wreaking havoc on America’s youth was comic books. At least that’s what a respected psychologist said.

Dr. Fredric Wertham was far from being some mid-century conservative cultural scold. After arriving in the United States from Germany in the 1920s, Wertham started to work with young people, especially those facing the effects of what we now call “structural racism.” His work with Black students in the 1930s was cited in the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education because it showed the damage segregation caused in education and American society. That 1954 Supreme Court decision was aimed at dismantling the doctrine of so-called “separate but equal” in public schools and, later, other taxpayer-funded institutions. But it was another thing that happened in 1954 that Wertham would, without knowing it, help to change the landscape of humor in the United States forever.

In April 1954 Wertham’s book Seduction of the Innocent was published. Subtitled “the influence of comic books on today’s youth,” Wertham outlined what he saw as dangerous themes of violence and sexual deviance in the cheap pulp magazines often popular with young people. Coinciding with the publication of Wertham’s book, the United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency held hearings on the scourge of comic books. The respected psychologist of Jewish background testified that according to his research, Batman and Wonder Woman were leading America’s youth astray. Wertham even compared the comic book industry’s impact on children to the horrors unleashed by Adolf Hitler.

Panic in Detroit

As Wertham received national attention by claiming comics were rotting the souls of children, the Motor City was ahead of the curve when it came to cracking down on funny books. Between 1948 and 1950, Detroit Police Commissioner Harry S. Toy raided newsstands around town. A fervent anti-communist, Toy felt comic books were not only leading Detroit’s kids into juvenile delinquency but corrupting their morals. (For more on this see The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare And How It Changed America by David Hajdu.)

At the 1954 Congressional hearing, one publisher took a rather controversial stance. He not only defended his right to publish but claimed kids had a similar Constitutional right to choose what they wanted to read. His name was William Gaines. Gaines, who took over his family’s Educational Comics business in the late 1940s, quickly shifted the focus to something different than what the major publishers were doing at the time. His company was an independent publisher so he knew he couldn’t go up against National (later known as DC Comics) and Atlas Comics (which later became Marvel) with similar fare. Gaines and his team had to be creative. The most popular of all of the comics Gaines published were horror and suspense stories with titles like The Haunt of Fear, The Vault of Horror, and Tales from the Crypt. Kids loved the scary, creepy, and sometimes gory stories.

Bernstein remembers getting hooked on Mad when he was 6 years old. “I saw it in a drugstore ... I had no idea what it was.”

tweet this

Congress was not impressed with Gaines’s reasoning nor his comics. Fearing a serious backlash, the major publishers got together and decided to create guidelines on what would be considered acceptable topics for comics. In September 1954, the Comics Code Authority was created. Similar to Hollywood’s production code during the same era, the Comics Code effectively drove a stake through the heart of many of the popular comics Gaines was publishing because even the use of the word “horror” was off-limits. For those interested in the social engineering the backers of the Comics Code sought to achieve, one provision made it clear: “Policemen, judges, government officials, and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.” (While aspects of the Comics Code loosened over time, it remained in effect essentially until 2011, when the last of the publishers, Archie Comics, abandoned it.)

While Gaines knew horror comics were dead thanks to the new restrictions, he thought one publication his team started the year before might be the new way forward — a humor comic called Mad. Also, the Comics Code had a loophole that only subjected self-censorship to comic books, not magazines. Coincidentally, Gaines started printing Mad as a full-size magazine and opened the door to more humorously creative ideas, and it soon took off — creating a cultural influence still seen today across print, film, television, and, even social media.

Between the covers

What made Mad special for its era and its style still influential today was its editors’, writers’, and artists’ different way of looking at American culture, politics, and consumerism than how the parents, pastors, and principals of their young readers wanted them to see the country. But it wasn’t biting social commentary that brought in many young Mad readers — it was the funny drawings.

Bernstein remembers getting hooked on Mad when he was 6 years old. He still has that issue in his collection — Super Special Number 18.

“I saw it in a drugstore,” he says. “I had in my hand a Star Trek coloring book, and as I was walking away from the newsstand I saw the big red logo of Mad. I had no idea what it was.” But thumbing through the pages, the young Bernstein was taken in by “the simple features — Don Martin with his four-panel crazy cartoons, Spy vs. Spy with its wordless play, and then the ‘fold-in’” — a recurring feature where the reader folds the page to reveal the gag — “which suddenly you’re not just reading the issue, you’re participating in the magazine.”

He adds, “So, it grew for me. It started as this shiny object which was wordless or fewer words that immediately grabbed you and then you expanded to reading it.”

One piece of social satire from the first issue Bernstein took home in 1975 that was likely over his head was the back cover — a cartoon image of “The Four Horsemen of the Metropolis” featuring the embodiments of Drugs, Graft, Pollution, and Slums riding rough over the cityscape of New York.

It was that balance between comic book sensibility and social commentary that made Mad a unique publishing enterprise. In a way, the need of its creators to speak truth to power made Mad magazine similar to Consumer Reports. In the history of publishing, those two titles were on a truly short list of magazines that turned away paid advertising for somewhat similar philosophical reasons. While Consumer Reports refused ads to be able to accurately review consumer goods without being charged with bias toward whomever was paying the bills, Mad refused ads so it could satirize American corporations and consumer culture without pulling any punches.

Mad’s art department turned its jaundiced eye towards creating fun house mirror-like versions of iconic ad campaigns of the era, often using similar layout and imagery and skewering products from beans to bras to BB guns and items from all the other store aisles in-between. But often the Mad creative team’s most pointed ad parodies targeted adult products — booze, beer, and, especially, tobacco for causing suffering and death. Some anti-smoking examples include a 1967 print parody of a popular TV ad for Kent where Mad used the cigarette brand name to create an acronym meaning “Knowledge Ends Needless Tumors.” Meanwhile, a 1969 fake ad called Cemetery cigarettes, a parody of the Century brand, features an actor dressed as pitchman Hitler bragging about how many millions of people he knocked off, but that’s nothing compared to the death toll of smoking. And a 1990 parody of Camel’s cartoon mascot Joe Camel has a doctor telling him smoking has caused him “cancer of the hump.” Once again, Mad magazine was a pioneer, with smoking bans becoming widespread in the 2000s. (While fewer people smoke today than when those parodies first went to print, sadly, cigarettes still kill over eight million people a year, according to a 2023 World Health Organization study.)

In a delicious irony connected to its parodies, Mad magazine’s offices at one point were along Madison Avenue — the same street where New York’s famed advertising industry was flourishing in mid-century America, the era captured in the Mad Men television series (2007-2015).

As Bernstein became a fanatical reader and collector of Mad, he says he can now see how it has informed his worldview throughout his life.

“It certainly gave me my basis of knowing to hold people accountable for what they say, especially corporations and, later on, politicians,” he says. “It informed how you can not only be silly with words, but you could also be witty. [Mad taught me] everyone was fair game because we are all imperfect. It helped me to see how we could make fun of each other and ourselves.”

When We Went Mad!

Bernstein conducted the first interviews for what would become this new documentary in 2008, starting with an opportunity to interview one of the early editors and architects of the Mad sensibility, Al Feldstein. Feldstein, who spent almost 30 years at Mad, was also responsible for the creative flash to repurpose an anti-Irish immigrant stereotype image used in old ads to become the magazine’s mascot: a goofy, gap-toothed boy Feldstein dubbed Alfred E. Neuman, borrowed from a pen name he used. After talking to Feldstein, Bernstein spent the better part of the next decade seeking more of the Mad minds to talk on camera.

“My goal was to interview as many living Mad artists, writers, editors,” he says. “I even reached out to family members of deceased artists and writers. When I first started out, everyone I reached out to was basically a cold call. I just explained to them what my goal was and my background as a Mad fan and how I wanted to tell the story completely, and I wanted to hear their specific story. I wanted them to talk about themselves and how they got to Mad and what it meant to them.”

Over time, Bernstein also knew that there had to be other people like him, fans who grew up reading Mad when they were young and credited it to helping to change the way they saw the world as adults. The first notable name he was able to get on camera was a friend of a creative at Mad magazine, comedian Gilbert Gottfried.

“I drove out to New York, met Gilbert at the Mad offices, and interviewed both him and [former Mad writer] Frank [Santopadre],” Bernstein says. “So, he was the first celebrity interview. I was put in touch with ‘Weird Al’ [Yankovic]’s agent, and we realized he was going to be performing at the Traverse City Cherry Fest one summer. We were able to get him to agree to it, so we all drove up to Traverse City from Detroit and met him in one of those portable office structures behind the stage before he went on to perform.”

Being an independent filmmaker from Detroit made it hard for Bernstein in two ways — first, finding the funding to keep production going and two, getting more notable people to talk to him on camera. In 2013, Bernstein decided to go online and see if Mad fans would step up to help him create his vision. A crowdfunding campaign on Kickstarter raised over $58,000 (which included a few dollars donated by the author of this article). After that, Bernstein knew there was a fantastic appreciation and appetite for what he was trying to do.

The next issue was how to get the various people influenced by the Mad sensibility to interview with this guy from flyover country who wasn’t connected to Hollywood. One day, Bernstein started cold calling and emailing production companies with documentaries on Netflix he felt might be interested in partnering with him to complete his Mad vision. One was to a company called Chassy Media, owned by TV host and podcaster Adam Carolla and his partner Nate Adams and mostly known for creating documentaries with a heavy interest in car culture. They were indeed interested, and having Carolla on board helped to open the door to more interviews with Hollywood creatives inspired by Mad including actor Bryan Cranston (Breaking Bad), director Judd Apatow (The 40-Year-Old Virgin), and director Quentin Tarantino (Pulp Fiction), plus the voiceover talent of actor Patrick Warburton (Seinfeld).

Being not only a fan but a collector of Mad, Bernstein infused his documentary with animations, text bubbles, and comic book panels to bring the kinetic, zany feel of the magazine to the screen. And the documentary’s blend of behind-the-scenes and celebrity interviews highlights how the Mad creative team were carrying forward their own humor sensibilities found around Jewish and immigrant enclaves in New York City, the music of Spike Jones, and the vaudeville-infused puns and satire of the Marx Brothers.

While readers loved the Mad sensibility, it could be tricky for them to pull off without getting into legal trouble, including a case that went to the highest court in the land. A 1964 copyright law case (Berlin v. E.C. Publications, Inc.) found songwriter Irving Berlin — best known for such popular classics as “White Christmas,” “Puttin’ on the Ritz,” and “There’s No Business Like Show Business” — suing Mad magazine over the publication of a 1961 issue featuring dozens of parody lyrics to some of Berlin’s best-loved songs for over $25 million in damages (almost $264 million today). Ultimately, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled Mad had a right to parody because no reasonable person would confuse the joke version with the original and thus damage Berlin’s right to make money from his original songs. The plaintiffs appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to hear the case.

Mad continued to be the top-selling American humor magazine throughout the 1960s, ultimately hitting a circulation peak of two million copies per issue in 1974, just as the magazine’s spiritual children like National Lampoon started to eat into its market with more adult-centered satire. Regardless, the humor team continued to push forward throughout the 1980s because, although it was sold in the 1960s to a bigger company, the original publisher was always able to keep the suits from running the show. But on June 3, 1992, Gaines, the man who ruled the Mad world for almost 40 years, died in his sleep at the age of 70. Without his leadership, the Mad creative team tried to continue on but soon found itself under the thumb of its corporate overlords, which would become Time-Warner and its DC Comics imprint.

While Bernstein was creating his documentary, Mad magazine was hit hard, becoming another victim of the decline of publishing in the digital era. In 2018 the magazine was moved from its New York City home to Los Angeles, where DC Comics could oversee its day-to-day operations. The last magazine of new content was published in October 2019. Since then, Mad is published several times a year featuring mostly compilations of older material. While the print version of Mad today is not what it once was, the sensibility its creative team birthed can be seen in places ranging from Saturday Night Live and The Onion to the entire discography of “Weird Al” to films like Airplane and the memes many of us share daily on social media.

Looking back on over a decade and a half of work, Bernstein’s feeling about his effort mirrors the team who started Mad almost 70 years ago — up against challenges, sure, but understanding that tenacity is always the key to creating something worthwhile.

“If it’s important enough to you, the project, whatever it is you’re doing, it’s important enough to you you just keep going ahead,” he says. “You don’t stop. There are always pauses … you just have to see it through, and you can’t worry about, ‘Oh my God, this is Year 14.’ It didn’t matter to me. I just needed to get to the end.”

Metro Detroiters can celebrate with Bernstein for the local premiere of When We Went Mad: The Unauthorized History of Mad Magazine starting at 7:30 p.m. on Thursday, Nov. 14 at the historic Redford Theatre; 17360 Lahser Rd., Detroit; redfordtheatre.com. Tickets are $10.