‘Living Frequency’ follows the mycelial threads of Black Detroit art from past to present

The show pays tributes to elders like Gilda Snowden, Shirley Woodson, Charles McGee, LeRoy Foster, and Marian Stephens

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

There’s something really annoying that happens when Black History Month rolls around. Magically, corporations and public institutions remember that Black people exist and run virtue signalling campaigns or heavy-handed displays of Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks. They missed the memo that Blackness is neither confined to the Civil Rights movement or the past, as our culture fuels the present and future.

It’s kind of like when white people post “I Have a Dream” quotes on MLK Day instead of, “The Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice.” It only tells one story.

But Detroit is the living embodiment of Black history in the making, especially when it comes to Black art. The mycelium that connects Black Detroit artists across generations bears fruit at Living Frequency: Honoring the Legacy of Black Artists in Detroit, an exhibit on display at Midtown’s Galerie Camille.

Curated by multidisciplinary artist James Charles Morris and Galerie Camille director Marta Carvajal, Living Frequency follows the mycelial threads of Detroit’s Black art scene from the past into the present. Each artist in the show created new work to pay tribute to the city’s influential Black artists like Gilda Snowden, Shirley Woodson, Charles McGee, LeRoy Foster, and Marian Stephens.

And while you could see this as a Black History Month exhibit (Morris says he was approached about curating the show specifically for this month), it’s a song that doesn’t beat you over the head with the same old tune about resilience and adversity.

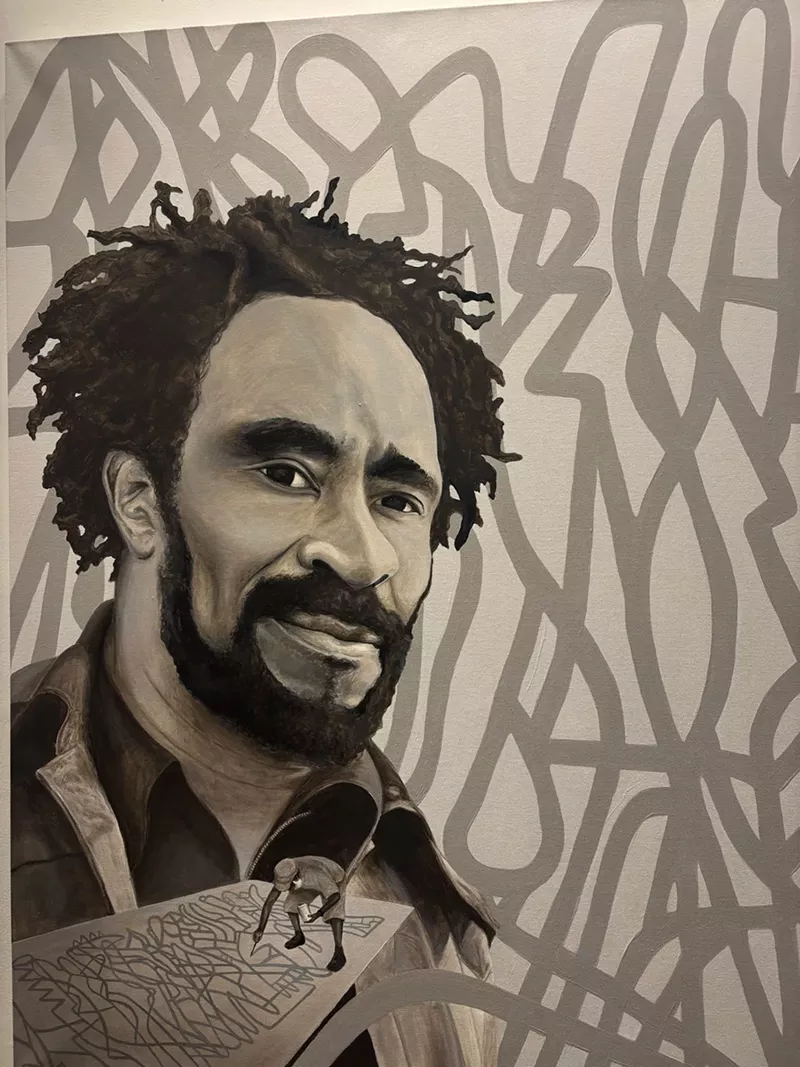

Oshun Williams goes monochrome in his painting of Marian Stephens, a former Cass Tech teacher who mentored countless artists like prominent muralist Sydney G. James. Phil Simpson, known for his trademark Detroit smile, paints a portrait of Joyce Ivory with a shimmering gold halo, and Joe Cazeno III’s portrait of a young Charles McGee with the eminent artist’s abstract patterns in the background is aptly titled, “Standing on the Back of Giants.”

“It's a beautiful melting pot of our scene really coming together to pay homage,” Morris says about the show.

Next to Ijania Cortez’s drawing of Harold Neal are Neal’s actual palette and a pair of Snowden’s paintbrushes, living relics of the two influential artists that belong in a museum. Down the street from Galerie Camille is a mural Cortez painted of Morris’s grandmother, the “great dame” of the Detroit art scene, Dell Pryor.

Darian “Saint” Greer, Breianna Jackson, Tylear Jefferson, Jonathan Kimble, Brian Nickson, Joshua Rainer, Miriam Uhura, and Jacob Zelecki also have work in this show.

Living Frequency is, in part, an extension of Morris’s archival platform called The Detroit Exhibit, which he started last year to preserve the story of Black artists in the city.

“Just because we don’t have a name for it, like the Harlem Renaissance or Black Wall Street, it [still] deserves that praise because a lot of firsts for Black artists in this country happened right here in Detroit,” Morris says.

Morris started The Detroit Exhibit following an exhibit called Art We Love Detroit where only about 10% of the artists shown were Black — a travesty in a majority-Black city with such a robust roster. To make matters worse, one of the pieces in that show was a clear rip-off of a Black artist whose work Morris knew and loved.

“I was mad because all that shows is another situation where an artist comes in, sees something he thinks is cool, then all of a sudden he wants to utilize it in his own work. Next thing you know, you’re whitewashing those who have already been here, and we have this long history,” he says. “The whole idea for the Detroit exhibit formed in my head to create a platform that tells a comprehensive story.”

Morris’s digital collage work an appearance with a piece dedicated to Snowden, but he also offers a more symbolic body of work with fabricated doors to some of Detroit’s oldest Black art institutions like Arts Extended run by Shirley Woodson, Cledie Taylor, and Marian Stephens; Pen and Palette Club, which was founded by the Detroit Urban League in the 1920s; and the Contemporary Studio, founded by the likes of Harold Neil, Charles McGee, Ernest Hardman, Henry King, and LeRoy Foster. All of these influential artists are also represented in the show.

“When thinking of ways to honor the institutions that paved the way for this community that we know, the only thing that made sense was the doors because at this period — this is going back to as far as almost 100 years that we have had a Black arts community here — but think about how many doors were shut,” Morris says. “These were the first doors to say you can come in and do your thing and explore and express the way you want. Arts Extended is still going on. Cledie Taylor about to turn 99.”

Living Frequency is a warm hug from Detroit’s Black artists who are walking in the footsteps of their elders while creating new pathways for those who will come behind them. What if Black History Month was about Black joy? What if it was about Black creativity full of so much vibrancy that it leaks out on the pavement like a can of yellow paint so bright and buzzing with life that its container couldn’t hold it? It would look something like Living Frequency.

Living Frequency: Honoring the Legacy of Black Artists in Detroit is on display at Galerie Camille until Feb. 28. For more information, see galeriecamille.com.

Published in conjunction with Midbrow.