Longtime readers know that, with every Metro Times gift guide, we make an effort to review as many of the books about Detroit as we can that came out during the last year. Each year, the list has grown, and now, it seems, everybody wants to write about Detroit. There's no way we can review them all. Some of them have come out so close to the holiday season that we could barely scan them, or couldn't obtain them at all. (And, frankly, a few of them were so execrable we didn't want to review them — we're looking at you, Daniel Greenup!) But, doing our darndest to help readers fill that literary stocking with Detroitica, we here try to include as many as we can.

First off, lots of appealing photographic books this year. Among the most impressive is Detroit's Historic Places of Worship, compiled and edited by Marla O. Collum, Barbara E. Krueger and Dorothy Kostuch, with photographs by the talented Dirk Bakker and a foreword by a man who knows a thing or two about architecture in Detroit, John Gallagher. The slightly oversize volume, featuring scores of full-color photographs along with histories of the churches and parishes, delivers on its promise beautifully. Some of the images are so impressive, you can almost hear the pipe organist striking a chord. Another similarly large (11 inches by 8.5 inches to be exact) photographic record is Michael H. Hodges' Michigan's Historic Railroad Stations. From functional depots to monuments to rail travel, Hodges offers excellent photographs of the stations, sets their context in history, shows how some have been repurposed, and, of course, shows how a few have become iconic ruins, including our own beloved Michigan Central Station in Detroit. For the Michigan railfan on your list, you need read no further.

Then come the smaller-format photo histories of the Images of America series, which usually sell for around $22 and tell the tale of some particular niche in the history of a given place. We received two of them this year, one of which was Detroit's Historic Water Works Park by Michael Daisy, a fascinating look at how Water Works Park went from one of the city's most popular recreation areas, with gaudy views, ambitious landscaping, stunning floral displays and first-rate architecture, to a place completely closed to the public. The other book, Detroit's Cass Corridor, is an interesting look back on that parcel of land between Cass and Third, from Michigan Avenue north, and the many lives it has led, from home of the gentry to home for Southern transplants to bastion of redevelopment under the "Midtown" banner. Unfortunately, some rookie errors (Allen Schaerges is the Mayor of Cass Corridor, not the Dally, and the owners of City Bird are the Linns, not the Lims) cast doubt upon the book's general accuracy. That said, the pictures of, say, Third Avenue in the 1960s, with all the buildings occupied and business signs blazing, will lift your eyebrows off your forehead.

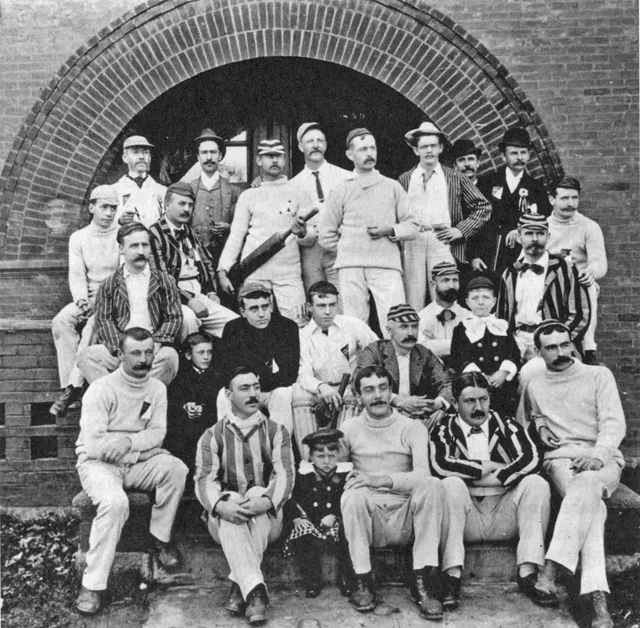

Rich with photos, but only to accent the history, is The Enduring Legacy of the Detroit Athletic Club: Driving the Motor City, by Ken Voyles and Mary Rodrique. Starting at the beginning, with the club opening in 1888 just north of what is now the Whitney restaurant, following it through to the "new" incarnation downtown (opened 1915) all the way to its renovation and preparations for the building's 100th anniversary, it's a thorough examination of the club, its auto baron membership, and the way the institution's history has been intertwined with the development — and dilemmas — of the city.

For the woman who appreciates art, you might consider Great Female Artists of Detroit by Suzanne Bilek. Maybe it's a stretch to include Frida Kahlo, who spent about a year here in town while her husband Diego painted the Detroit Industry murals at the Detroit Institute of Arts, but few will complain about it. Other artists of note include Niagara and Gilda Snowden, as well as many others readers may be unfamiliar with. The small, 150-odd page book does have many full-color reproductions and stories of women in art going back to the 1800s.

Normally, each year we find a bevy of books about the more musical dudes from Detroit, guys with guitars or the powerful men behind the sounds of Motown and beyond. And so it's a refreshing change that the books about music we found this year are books about musical women.

Mary Wells: The Tumultuous Life of Motown's First Superstar by Peter Benjaminson is based on deathbed interviews with Wells, and delves into the grit behind the scenes — the sex, drugs and violence — including a stormy affair with Jackie Wilson. And, co-written with David Ritz, we have Bettye LaVette's A Woman Like Me, the tell-all autobiography offers some eye-opening looks at the record biz going back to the 1960s; although she wasn't signed to Motown, she was very much a part of the Motown dramas and culture. Lavette and Ritz then recount her descent into poverty and despair after she failed to become a star. The ending, thankfully, is more upbeat, after her rediscovery, which vaulted her back into the spotlight.

This year also saw publication of The Broken Table: The Detroit Newspaper Strike and the State of American Labor by Chris Rhomberg. Rhomberg's book chronicles the strike, including the shameful way the newspapers paid off suburban police departments and hired private guards in riot gear, clearly escalating violence against the strikers. It's an unsettling look at what became a pivotal labor battle, and Rhomberg shows what happens when management doesn't simply try to bargain over the negotiation table, but seeks to take that table away entirely via unconditional offers. Tying in the events of 20 years ago with the state of labor today, it's a chilling story, not overly academic in its telling, one that could appeal to the fan of labor on your holiday gift list, or even the younger reader with a blossoming social conscience who may not remember the events of those days.

Speaking of labor-oriented titles about Detroit, it has been at least five years since the publication of a new edition of the classic Black Detroit and the Rise of the UAW, and now we have Beth Tompkins Bates' The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford. We've only thumbed through it, but it seems like engrossing material, as Ford's relationship with black workers was a special one, apparently liberal but paternalistic in practice, a complicated relationship based on undermining labor in the workplaces and enforcing segregation outside the workplace. This niche study should appeal to anybody interested in what really went down before the final unionization of Ford in 1941.

For the despairing hockey fan weeping his way through this year's NHL nonseason, perhaps you can offer as a palliative Hockeytown Doc: A Half-Century of Red Wings Stories from Howe to Yzerman, by Dr. John Finley. As team physician for the Red Wings, Finley cared for the team from the glory days of the "production line" 1950s to the late 1990s. Now these tales are told in Finley's new book, as well as some of his views as a doctor on concussions, eye injuries and skate cuts. Hearing about Finley sewing Kevin Miller's gums back together after a fractured maxilla, or giving Terry Sawchuck a "surprise nose job" after the bottom of it was lifted away from his face by a wild puck, you realize a guy like Finley has to be as quick repairing a Red Wing as a pit crew does a racecar. All in all, this book could help cure this year's Red Wing blues.

On the architectural tip, this year also saw publication of a thorough overview of the towers and townhouses of Lafayette Park, Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies: Lafayette Park, Detroit by Danielle Aubert, Lana Cavar and Natasha Chandani. Lovers of modernism will find much here to enjoy, particularly the lovingly photographed portraits of residents, and the ways they've taken identical spaces and turned them into expressions of their individuality. Of course, many new urbanists have taken a mixed view of the projects, which swept away a densely populated African-American neighborhood and replaced it with a low-density, upper-income largely white development. That subject, thankfully, is tastefully addressed here, though not lingered over long. Perhaps it should have been, as the "success" of Lafayette Park is founded on a deeper cautionary tale of "urban renewal" in American inner cities. But for those who love mid-century design and architecture, especially as it is expressed in this monumental project, this book will be a joy to thumb through.

Also betokening renewed interest in Detroit and its architectural heritage is this year's reissue of the 1968 classic The Buildings of Detroit: A History by Hawkins Ferry and W. Hawkins Ferry, a 500-page behemoth many readers considered exhaustive and excellent. But, honestly, the one we're waiting for should be out by the time this is published. It's Forgotten Landmarks of Detroit, by Dan Austin. See, Detroit has always had a strange relationship with its past; maybe its because we burned to the ground a few centuries ago. Or maybe it's the result of being the Motor City; given the "model year" mentality, we may regard that which is old as inherently obsolete and be all too ready to sweep it away for something newer. In his books and on his website, historicdetroit.org, Austin has been sharing his histories on what we've sacrificed, and his painstakingly researched histories are sometimes as close as you can get to the real-gone real thing. Weighing in at more than 260 pages, with plenty of lovely archival photos, Austin's book will tell the story behind 15 landmarks that are now gone forever, and it looks like a doozy. See below for details on his book release party.

A couple books this year centered on odd identity struggles in inner-city Detroit. We wished somebody would have sent us a copy of Runnin' With the Devil: Growing Up Black and Metal in Detroit Rock City by Scott T. Sterling; although it sounds like it's mostly one long love letter to Van Halen, we wonder what insights Sterling has to offer on African-Americans enthralled by metal. But no Detroit tale that touched on the racial divide in Detroit this year was more personal or compelling than Tears for My City: An Autobiography of a Detroit White Boy by Dean Dimitrieski. In 1973, Dimitrieski's family left Macedonia and came to the United States, moving into a house on Detroit's east side. In his book, he tells how he, his parents and his sister weathered what became an increasingly rough neighborhood. Now, Dimitrieski is no professional storyteller, and his style is not literary. This is a simple, vernacular history of one family's struggle to adapt to one of the harshest environments in urban America. He tells it all: the beat-downs, the shootings, the killings, the "drop zones" where bodies were discarded. He makes friends with some of the main drug dealers of the day, barely disguised with such names as "Ferrari Jones" and "White Boy Tom." Some of the tales, such as that of drug couriers landing small jets on McDougall, strain the reader's credulity, but most of the narrative is all too believable. The careful photos of the author sitting on his old stoop at the end, and one photo showing the rumored location of the buried millions of "White Boy Tom" demonstrate a sincere longing on Dimitrieski's part for the old days. Over and over again, Dimitrieski, whose family moved to the suburbs when he was 20, asks the reader why he looks back with such nostalgia to a time that he admits was full of fear and horrors. It gives the book a tension that's not soon forgotten.

Another book that came in a bit late for us to really read through it was Detroit City Is the Place to Be: The Afterlife of an American Metropolis by Mark Binelli. Binelli seems like a nice enough guy, originally from metro Detroit, now a contributing editor to Rolling Stone and living out in New York City. He came to live in Detroit for a while and spent time with a good number of people at Metro Times know well, including Detroitblogger John, Mark Covington, Grace Lee Boggs, Tyree Guyton and many more. He hits places known mostly to insiders, such as the Carpet House, Catherine Ferguson Academy, or the wasteland that is the I-94 "Industrial Park." Following his guides, paying attention to a murder trial, chronicling the efforts Detroit Works, and speaking to firemen and police, the book is a good read. But on our quick perusal, the book seemed to be a bit too focused on the ruins, the urban ills, the designs of small-time do-gooders and the well-meaning efforts of large players. Binelli seems to offer a few glances at the elephant in the room: dysfunctional metropolitan politics in which suburban leaders have poached off the city for decades and now largely sit in smug, self-satisfied comfort in bigfoot houses and refuse to invest in the urban core — and often don't believe one is necessary. You can focus all you want on the troubled city, but without acknowledging the overt racism and self-congratulatory invective heaped on the city by those with the most subsidies, how do you come to understand what happened here? Then again, we speed-read it as fast as we could before deadline. If we're wrong, our apologies go to Binelli. And, despite these perceived faults, it is engaging; you may well buy it yourself and make your own call.

One book that does take it all in is Detroit: A Biography by Scott Martelle. A third-generation journalist, Scott Martelle lived and worked in Detroit for years, participating in the Detroit newspaper strike in 1995. Having been embedded in Detroit, and with a deep understanding of working-class America (Martelle also authored Blood Passion, an account of the Ludlow Massacre, a particularly bloody chapter in labor history), Martelle tells the story of the city from its inception to its zenith to today, finding every problematic throughline, exposing every myth, diagnosing every overstatement. For readers who were intimidated by academic histories such as Thomas Sugrue's Origins of the Urban Crisis, Martelle's book may be a better way to dodge the mythology behind Detroit's decline and examine the underlying causes. What's more, Martelle's take on the calamity that is Detroit is not just true but also fair. While acknowledging the forces behind our city's decay, he doesn't excuse the destructive decisions that were made, nor does he feel that pointing fingers will find a way forward. Perhaps once we, as a metropolitan region, are able to see our own history as clearly as Martelle has summarized it, we may be in a position to avoid the easy answers and find the tough path to reclaiming our greatness.

A book release party for Dan Austin's Forgotten Landmarks of Detroit will take place at 4-7 p.m. Sunday, Nov. 25, at City Bird, 460 W. Canfield St., Detroit.

Michael Jackman is senior editor of Metro Times. Send comments to [email protected].