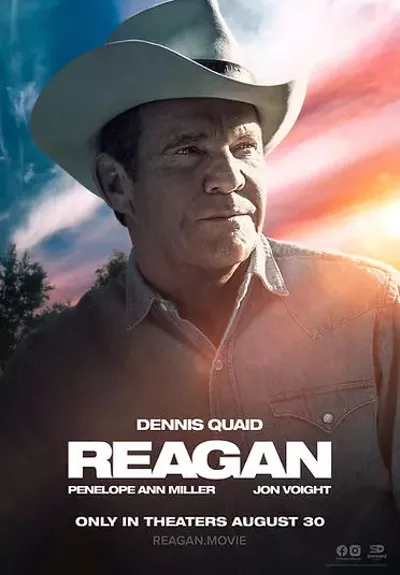

Ronald Reagan’s presidency lasted eight long years. The current film Reagan only feels that lengthy. At two hours and 15 minutes, this tedious biopic is a cliché-cluttered mix of melodrama and hagiography with all the subtlety and nuance of a superhero comic book.

Nevertheless, an afternoon screening last week in a suburban Detroit theater ended with robust applause from the audience. During a presidential election year, the release timing is ideal. Reagan left office in 1989 and died in 2004, but this Reagan pic shows how his myth lives on.

Like former president and current Republican candidate Donald Trump, Reagan (played here by Dennis Quaid) entered politics through show business: Trump from “reality” television and Reagan from Hollywood movies. Trump often praises politicians if they look like they come from “central casting.”

In this sense, Reagan was the real deal. He was a genuine professional screen performer who skillfully used soothing words and his Sunny Jim persona to disguise racial animus, to lie about arms-for-hostages, and to wage a disastrous “War on Drugs” while willfully ignoring the AIDS epidemic and inflicting trickle-down economics to favor Wall Street tycoons.

Hollywood itself coined the cliché “greed is good” for this decade of decadence. Rather than deal with Reagan’s flaws and mistakes, this Reagan script moves on two, simple and parallel tracks: Ronald Reagan brought down Soviet Union communism and Ronald Reagan really loved his second wife, Nancy.

The rest must be just fake news. So: In honor of the return of football, let’s reminisce on the difference between reality and myth as it applies to Reagan and what might be his best-known movie role: That of George Gipp of Notre Dame in the 1940 film Knute Rockne: All-American.

Flash back to 1979. I reported an “advance piece” on that year’s Michigan-Notre Dame game. Reagan, former governor of California, was running for president. I lobbied his staff for a telephone interview with Reagan about his role as Gipp, who grew up in Calumet, in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

In particular, I wanted to ask Reagan about the famous deathbed scene in which Gipp urges coach Rockne (Pat O’Brien) to tell the Fighting Irish — when they need a comeback — to win one for the Gipper. Later in the film, “Rockne” does just this at halftime of the 1928 victory over Army.

After Reagan’s people turned me down, I did the next best thing: I got O’Brien’s phone number from Freep colleague Shirley Eder who said O’Brien loved to talk. I called him and learned something: Both the deathbed scene and the halftime speech were no longer in the movie, which O’Brien watched religiously whenever it appeared on TV.

Irked by this, O’Brien blamed “Warner Brothers in all their wisdom . . . Probably some idiot cutter who didn’t like football.”

I checked into it and discovered the real reason: It was mistakenly believed at that time in the business of movie syndication on TV that the Gipp family had demanded the cuts.

Only one problem: The family never demanded the cuts. But this little myth became attached to the bigger myth about their deathbed conversation.

“The best scene in the movie!” O’Brien said.

In the dialogue, Gipp tells Rockne: “Rock, some day, when the team’s up against it, the breaks are beating the boys, ask ‘em to go in there with all they’ve got, win just one for the Gipper. I don’t know where I’ll be then, but I’ll know about it. I’ll be happy.”

Reagan/Gipp — dying of pneumonia — then finishes speaking, closes his eyes, and drops his hand as ominous music swells. The movie dialogue was written after both men were long dead.

In that Reagan is on screen for only seven minutes in the film, it is certainly a pivotal plot point. Years later, the mistake was cleared up. Both deleted scenes have been restored to the film for contemporary TV showings. O’Brien died in 1983.

Late in the conversation, I asked O’Brien if he planned to watch that year’s game.

“What do you mean, am I going to watch?” O’Brien said. “Am I a Catholic?”

O’Brien also spontaneously recited the first four paragraphs of Grantland Rice’s famous “Four Horseman” story about the Notre Dame-Army game of 1924 which Rice began with “Outlined against a blue-gray October sky . . .”

And so on. When I asked O’Brien to predict the outcome of the next game, he replied: “Maybe they’ll part the blue-gray skies and help the boys tomorrow when they’re thrown to the Wolverines.” As it turned out, Notre Dame defeated Michigan that day, 12-10, on a blocked field goal at the last second.

It is unlikely that any scenes from the current Reagan movie will be censored in any way. If they wanted to cut a few, they might start with the one in which British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher shouts at her TV “Well done, cowboy!” when Reagan tells Mikhail Gorbachev of the Soviet Union to tear down the Berlin wall.

Better yet, leave it in, for unintentional humor. Same with the treacly love scenes between Ronnie and Nancy (and they love horses almost as much as each other). And critics have scalded Jon Voight for his portrayal of a retired Soviet intelligence officer who also narrates the timeline.

They say his “Viktor Petrovich” accent is like that of the cartoon spy Boris Badenov from the syndicated series about Rocky and Bullwinkle from the Cold War era. This may accidentally harmonize with the funny-pages sophistication of the script.

Other viewers may find Voight’s scenes to be the movie’s most poignant, particularly when he is confined to a small apartment (which feels a little like a jail cell) as he recounts to a young, ambitious colleague all about the fall of the Soviet Union and Reagan’s role in it.

A laugh-out-loud moment comes — this time intentionally — when Reagan shows three quick scenes of three successive funerals for three successive Soviet leaders.

Less intentionally funny is the scene — a real groaner — in which Tip O’Neill, the Democratic Speaker of the House, visits the Republican Reagan in the hospital after a serious assassination attempt.

O’Neill brings the rosary beads. Together, they pray. It’s a scene worthy of “Rock” and “the Gipper” in the hospital. But Reagan doesn’t die! If only Pat O’Brien were still around to play the part of O’Neill. Win one for the Tipper.