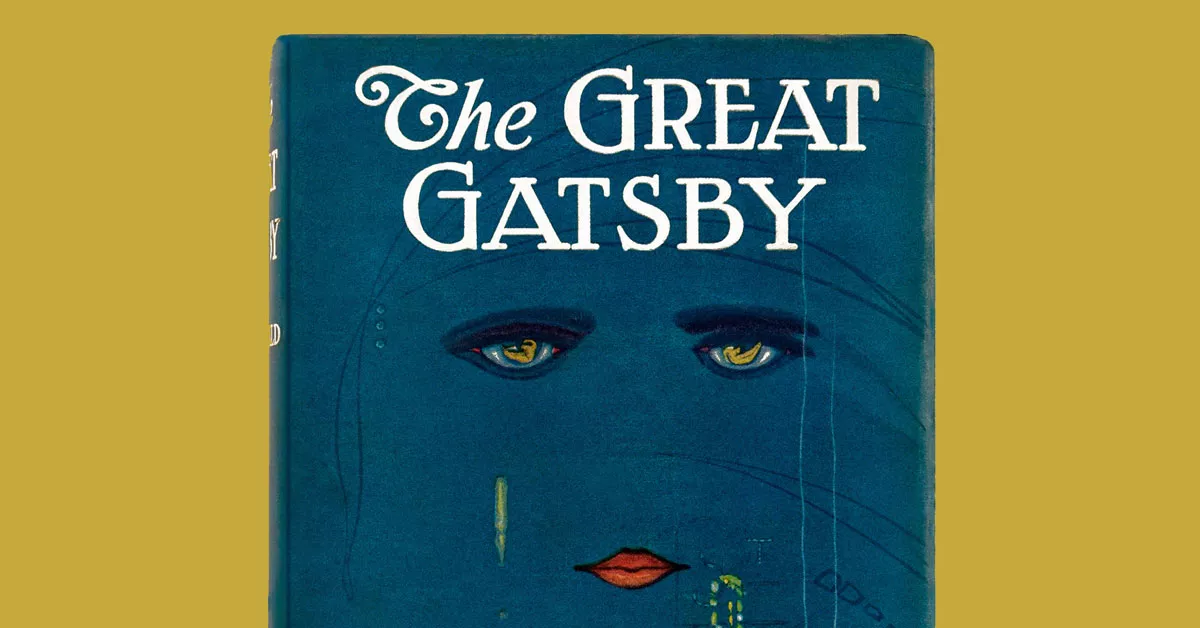

Although most of The Great Gatsby takes place in the wealthy Long Island suburbs of New York City, our own Motor City plays a bit part. This April marks one full century since its publication in 1925. In that much of Gatsby still rings true today, let’s begin the 2025 retrospectives.

The protagonist, Jay Gatsby, is a mysterious millionaire, a host of grand parties at his mansion and, quite possibly, a bootlegger of alcohol during Prohibition. The novel’s narrator, Nick Carraway, tells of over-hearing Gatsby on the telephone. The ellipsis dots and italics are by the author, F. Scott Fitzgerald.

“I can’t talk now, old sport ... I said a small town ... He must know what a small town is ... Well, he’s no use to us if Detroit is his idea of a small town.”

At the time, Detroit had the fourth-largest population in the United States, nearly one million people, and its proximity to Canada attracted bootleggers during a decade called both “The Roaring Twenties” and “The Jazz Age.”

Later in this short and brilliant novel about the illusions of the American Dream, a telephone operator (there used to be such people) tells narrator Nick the line to Gatsby’s mansion is being kept open for a long-distance call from Detroit. Such were the pleasant little finds last week in reading Gatsby for the 10th time (or maybe the 15th).

The book has aged well. At 100, Gatsby still feels contemporary, as if it could have been written today about shallow people and money lust. But it would need a few revisions of criminal enterprises and negative ethnic stereotypes. For instance: a modern Jay Gatsby would not be an alcohol bootlegger.

He’d deal cocaine or some other drug or maybe run a Ponzi scheme. And Gatsby’s shady business “gonnegtion” would not be the hideous Meyer Wolfsheim, a caricature of a Jewish money manipulator, a stereotype all too common in American literature before World War II.

Instead, the Wolfsheim of 2025 would likely be Hispanic or Middle Eastern, the accent and stereotypes adjusted accordingly. But Wolfsheim is merely part of the second tier in Fitzgerald’s vivid cast. The stars carry the simple plot.

For the female (Daisy Buchanan), it is based on the old trope of “torn between two lovers.” Another archetype is personified in Gatsby, a middle-class, New Money striver. He is a delusional, lovesick man trying to rekindle a lost romance even though his old flame is now married to a wealthy man of Old Money — Tom Buchanan — and they have a child.

Mix in adultery, alcohol, and arrogance and you’ve got all the ingredients for the car crash and the shootings which leave three characters dead at the end of the tale. All of this swirls around Buchanan, a man who would fit easily into a 21st. Century novel.

He is a racist and a sexist who bullies people with his big bucks, bulk, and bluster. Buchanan forecasts “replacement theory” long before the alt-right coined the term. He touts a book called The Rise of the Colored Race.

“If we don’t look out, the white race will be — will be utterly submerged . . . It’s up to us who are the dominant race to watch out or these other races will have control of things.” Later, he muses: “Next, they’ll throw everything overboard and have intermarriage between black and white.”

A former football star at Yale, Buchanan takes offense when his mistress (Myrtle Wilson) keeps repeating the name of Buchanan’s wife at an impromptu party in their Manhattan love nest. From the book:

“I’ll say it whenever I want to! Daisy! Dai —”

Making a short, deft movement, Tom Buchanan broke her nose with an open hand.

Had Gatsby offered just a clear plot and obvious characters, few would probably read it today or even remember it. But it also provides prose that is melodic, poetic, and lyrical. Fitzgerald writes words the way Eric Clapton bleeds notes from the strings of an acoustic guitar.

And that makes Gatsby one of those books especially pleasing to the ear on recorded audio readings. Many versions are free on the internet. The copyright has expired, but Fitzgerald’s words endure. Hear how narrator Nick describes Gatsby’s party guests.

I have forgotten their names — Jaqueline, I think, or else Consuela, or Gloria or Judy or June, and their last names were either the melodious names of flowers and months or the sterner ones of the great American capitalists whose cousins, if pressed, they would confess themselves to be.

(Students take note: The previous was a 49-word sentence that ends in iambic pentameter).

Fitzgerald’s tuned ear heard the music of words and voices. Through narrator Nick, he makes much of how Daisy speaks.

“It was the kind of voice that the ear follows up and down as if each speech is an arrangement of notes that will never be played again,” Nick tells us. Later, Gatsby tells Nick: “Her voice is full of money.” And the wealth of the Buchanans inspires one of Fitzgerald’s best-remembered sentences.

They were careless people, Tom and Daisy — they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made…

When first published, Gatsby was less than a big success. The New York World ran a headline that said “Fitzgerald’s latest: A dud.” The New York Times was more generous, writing: “This is a book of potent overtones, a curious book, a mystical, glamorous story of today.”

Fitzgerald himself had no doubts about its quality. “I think my novel is about the best American novel ever written,” he wrote to his editor. He wasn’t far off the mark. Most book buffs would put it in their American Top 10. At 47,094 words, you can read Gatsby in one evening, two at the most.

And you should.