In anticipation of the World Series between the New York Yankees and the Los Angeles Dodgers, I finally read Roger Kahn’s classic baseball book The Boys of Summer. It chronicles, in part, the Dodgers’ 1952 season that ended with New York beating Brooklyn in a seven-game World Series.

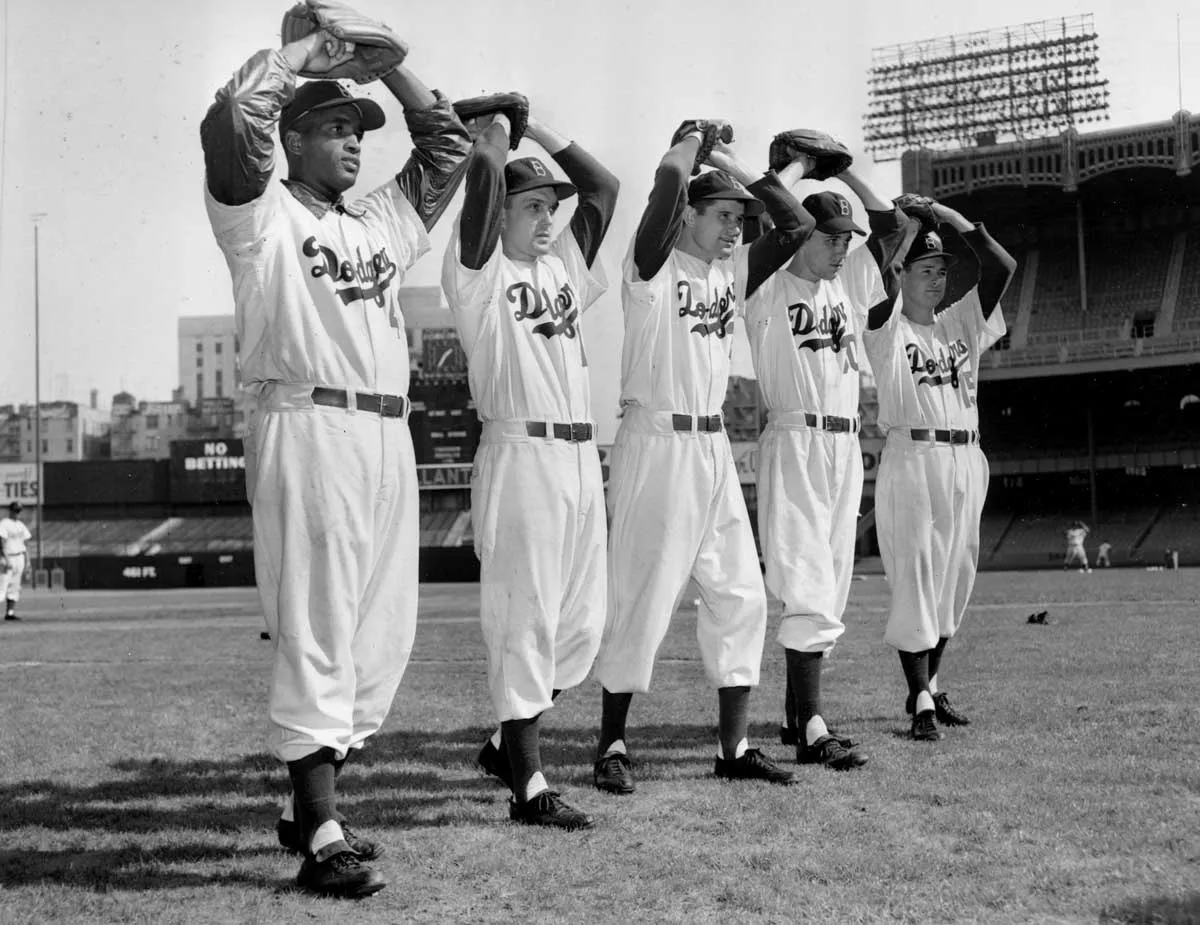

With Jackie Robinson, Joe Black, Roy Campanella, and others, that generation of Dodgers racially integrated Major League Baseball as the culture of the National Pastime changed in many ways. And the book also explores the mixed fortunes of those Brooklyn stars after retirement.

Among the poignant paragraphs in a sentimental saga are those about ex-Dodger Carl Furillo, employed in the early 1970s to install elevator doors in the Twin Towers under construction in New York. (The book was published in 1972.)

Kahn interviews Furillo at the job site of the skyscraper, “the World Trade Center, rising bright, massive, inhuman, at the foot of Manhattan Island.” One Kahn observation is weirdly and unintentionally prophetic.

“One tower of the World Trade Center had been topped and sheathed,” Kahn writes. “An aluminum hulk against the sky. The other tower still showed girders . . . the sprawling site had acquired the scarred desolation that comes with construction or with aerial bombardment.”

As we know, neither the Twin Towers of Manhattan nor Ebbets Field of Brooklyn still stand. But the Dodgers survived and thrived after moving to sunny Los Angeles in 1958. This year, by demolishing the Yankees in five games, the Dodgers took their eighth title, all but one since changing coasts.

To compare and contrast these distinctly different eras, I divided my time between this year’s Series telecasts on Fox and two surviving telecasts of the 1952 Series on NBC, both in Brooklyn. They were recorded on kinescope film.

Viewing them now is startling. First, there’s the difference between black-and-white television of the mid-20th Century and the color, high-definition telecasts of the early 21st. More cameras and better closeups now. And no replays then.

Other differences are more subtle.

For instance: Some players in the ’52 Series still left their gloves on the grass between innings. Their baggy uniforms lacked today’s sleek tailoring and lighter fabrics. If batters wore head protection, it must have been the old, hard “shells” beneath cloth caps.

When Mickey Mantle of the Yankees hits a home run in Game 6, he sprints around the Flatbush infield at nearly a full trot with none of the preening we see today. But, in other ways, you realize that, in baseball, the more things change, the more they stay the same, or at least return to old ways.

For instance: In the ’52 Series, the pace of the games is brisk. Batters rarely leave the box, and only briefly. Pitchers deal every 10 to 15 seconds. Hard grounders break through the infield because the fielders aren’t bunched into a one-sided, defensive shift.

Mercifully, 21st-Century baseball recently legislated against the shift. And, by instituting a pitch clock, it has restored the tempo to almost what it was in 1952 before the pitcher/batter delays of recent decades. What’s old is new. Back to the future, or at least to the present.

In addition, the old films provide spiritual time travel back to a different era, the last months of the Truman administration, when games were played in the afternoons, not at night. And 1952 was the final season of a 16-team major league configuration that had not changed for 50 years.

Immediately afterward, the Braves moved from Boston to Milwaukee; then the Athletics moved from Philadelphia to Kansas City; then the Browns moved from St. Louis to Baltimore and became the Orioles; and then the Giants moved from New York to San Francisco while the Dodgers moved from Brooklyn to Los Angeles.

Later decades brought expansion, expanded playoffs, artificial turf, covered stadiums, and announcers like John Smoltz of Fox who knows a great deal about baseball but talks so much he doesn’t let the game breathe. You notice this in contrast to Red Barber and Mel Allen, who announced the Series in ’52.

Instead of conversing with each other, the way announcers do now, Barber and Allen speak directly to the viewer, rarely interrupting or bantering. Their measured silences between pitches allow ambient crowd sounds to be audible without jolts of “walk-up music” or loud blasts of artificial, recorded noise.

Another comforting aspect about watching two eras simultaneously is to see the uniforms, with team logos across the front of the shirts. Even 72 years later, the designs are identical:

The cursive, blue “Dodgers” on their white home laundry with the red numerals right above the heart. (Even in black and white, you can tell it’s red). The Yankees in their road grays with “NEW” on one side of the buttons and “YORK” on the other. Then, as now, no names on their backs.

And what would Kahn’s Boys of Summer think of the 2024 Series and its TV presentation?

Would “Dem Bums” of Brooklyn — who integrated baseball — be surprised that the Dodgers were led this season by Japanese stars like Shohei Ohtani and Yoshinobu Yamamoto and that many stars on many teams are Latin American?

Would they have appreciated pre-game rap performances from Ice Cube in L.A. and Fat Joe in N.Y.? They might have chuckled knowingly when two Yankee Stadium fans were ejected from their front-row seats after strong-arming a foul ball catch from the glove of Dodgers’ right fielder Mookie Betts.

Perhaps they’d be puzzled by the gambling commercials and the three-minute breaks between half-innings. They might’ve been disappointed that the marquee matchup between Ohtani and Aaron Judge of the Yankees fell flat due to Ohtani’s shoulder injury and Judge’s extraordinary slump.

Judge’s drought ended early in the final game with a home run and a brilliant, crashing catch against the centerfield wall. But Judge’s gruesome error in the fifth set up two more atrocious fielding plays by teammates in the same inning as the Yankees squandered a 5-0 lead and fell into a 5-5 tie.

Even though the Yankees later took a 6-5 lead, their bullpen couldn’t hold it and the Dodgers — clearly the best team, sometimes by default — won, 7-6, to clinch the championship.

In retrospect, Los Angeles really clinched it in Game 1, in Chavez Ravine, when Freddie Freeman of the Dodgers — a 35-year-old star hobbled by an injured ankle — hit a grand-slam home run with two outs in the 10th inning to give the Dodgers a come-from-behind, 6-3 victory that prophesied the whole shebang.

Due to more homers and other heroics, Freeman went on to become Most Valuable Player and the casting was appropriately Hollywood: a melodically-named, strong-featured guy whose made-for-the-screen face looks like a lead actor in an action-adventure movie.

In Yankee Stadium itself, the cameras showed fan-held signs that said “Freddie, Please Stop” and “Enough Already, Freddie.” Oh, and, behind his back, baseball people whisper that Freeman is one of the nicest guys in the sport. And his three-year-old son, Maximus, recently survived a dangerous disease.

Enough plot points? In the baseball summer of 2096 — 72 seasons from now — fans can look back at primitive telecasts of the 2024 Series and marvel at how this timeless game charms us over the years, decades and centuries with legends and lore of storybook heroes like Freddie Freakin’ Freeman.