Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Late this winter, my Hamtramck buddies Steve Cherry and Jeffrey Fournier asked me to join them canoe-camping on the Au Sable River in northern Michigan. After long months trapped in the city, I was psyched to get away to nature. I agreed instantly, took time off work, and looked forward to our getaway longingly. Cherry had done this stretch of the Au Sable before, and was familiar with the various stops along the way where camping was free to canoeists, a kind of subsidy for the canoe liveries that dot Mio's main drag. He scheduled us to rent canoes from the Hinchman Acres canoe livery, and we drove up together in Fournier's truck the last week of May. Once there, an old-timer set us up with canoes, took our money, and scheduled us for a few days on the river.

The livery van dropped us off at a sandy river slope just outside Mio, and laid out our crafts for us. Cherry had a bunch of 3-mil contractors' bags to pack away our gear, just in case we spilled out of our canoes. He had a clever way of sealing them, pushing all the air out, then twisting the top of the bag until it was long and thin, then bending it back on itself and tying it off with thin rope. It took a while to get it right, and at least two sets of hands to do the job, but the seal was impressive. No water would get in there.

Soon we were about ready to push off into the water. A few other people were starting off ahead of us, rare travelers on this chilly, damp May afternoon. I looked over at them and saw them dressed in rain gear, despite the lack of rainfall. Cherry took out his rain poncho and put it on. Where was mine? Where was Fournier's? In our haste to pack our waterproof bags, we'd packed them away as well. Did we want to open the waterproof bags, then go through the trouble of finding our ponchos and resealing them? Nah, we were OK. It wasn't raining. We pushed off.

I'd never canoed solo before, and I must say you feel a bit more secure in your balance than you do canoeing with a partner. You know where your weight is while you move, and I didn't miss the unexpected jolts and tilts of having somebody up front. The tradeoff is that you do lose a certain amount of steering power. All the more reason to work on your J-stroke, pushing with your oar, then straightening it out for a moment like a rudder. I've heard the best canoeists seldom have to switch sides, though I switch it up a lot, especially in a current.

At some points on the Au Sable, you pass a bunch of tacky 1940s getaways, million-dollar hillside dream homes and manicured lawns, but this part of the river just outside Mio seemed wild and natural. Late May meant few bugs, but swallows darted around our watercraft to gobble what bugs there were. We even saw two bald eagles soar away from us when we disturbed them, a beautiful sight. But wildness also means there were some hazards to take seriously: fallen dead trees waiting to snag you and turn your canoe sideways, dead branches ready to take an eye out, eddies whirling you off-course and into danger. Luckily, the water was high, which meant we were less likely to founder on rocks.

Then the rain started. At first, just a gentle patter of drops, darkening the cotton of my light jacket. Then came a steadier drizzle of rain, dampening my hat, shoulders and pants. The wind picked up, turning our canoes into sails, pushing us sideways, seemingly whenever a particularly dangerous looking hazard lurked to that side. Sure, maybe once or twice the strong breeze blew at our backs, but mostly it toyed with us. I struggled with my oar to outpace it, but as some dead tree or white water came closer, I'd have to brake with my oar on the other side, saving me from danger but slowing me down. Then I'd paddle like mad to catch up with Cherry and Fournier, already far ahead.

I'm not sure when exhaustion set in. After an hour, I realized that working at a newspaper can turn you into a deskbound weakling. Fighting the wind, the current, shivering in the rain, struggling to keep up with my party, I felt my face turning grim. How long could I keep this up? Would we make it to our campsite? The way the river twisted and turned, who knew where we were?

Cherry seemed to be an expert canoeist, sliding ahead without apparent effort, warm and dry under his hat and poncho in what was now a driving rain. I caught up with Fournier, who was now, like me, soaked through entirely, his black cotton shirt sticking to his skin, his jeans dark and wet. He looked over at me with an expression that said it all: the ultimate look of hapless anguish, eyes wide, a slight rictus of the mouth, an I-am-about-to-go-into-fucking-shock face. We were in trouble unless we found land soon. We were in luck. Cherry pointed his oar ahead to our campsite, and we maneuvered our canoes in delicately.

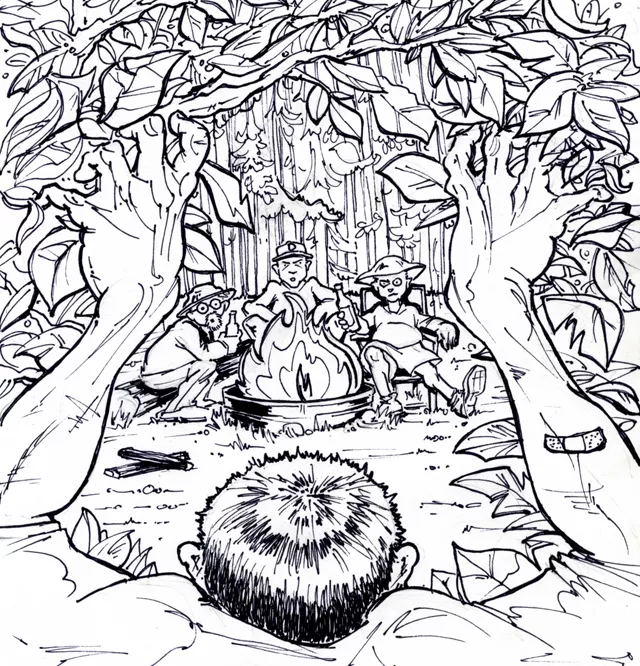

Morale was low. On a normal canoe trip, Cherry told us, the party would simply grab a cooler and some chairs and have a few beers before even thinking of setting up, but as wet and cold as we were, we needed to take action. We humped all our gear up the hill, put the canoes on dry land, rigged up a fly where we could take shelter from the rain that now fell in a steady mist, changed into some dry clothes and ponchos, set up our tents, got a fire going, even found a dead tree to saw down for firewood. After a few hours of work, camp was built, and we were seated around a fire, Cherry splitting the dry, dead wood into chunks with a hatchet to feed the flames, our dirty, wet clothes sizzling on the metal fire ring, a small transistor radio barking out classic rock hits from "The Bear." Cherry had also brought a small grill, and we cooked up a few small steaks and wolfed them down. Food seldom tastes as good as when you're exhausted, cold, wet, hungry and in the middle of nowhere.

Though there was little conversation, there was something we vocally agreed on: At least we were away from it all. That was why we'd been looking forward so much to this trip, our getaway, our retreat from society and its ills. We had gotten up early, driven hundreds of miles, embarked on a trip with some dangers, faced some hardship, and now, on a wet and rainy afternoon somewhere on the Au Sable River, we had found our peaceful reward. We nursed our cold, adult beverages, speaking little, enjoying the calm.

At least until we heard a rustling in the trees.

We saw a young woman walking with a dog on a leash, a strange twentysomething dude following behind her.

"Oh, hi," she said. "We didn't think anybody would be camping here this early!"

How close were we to civilization after all? Was it just an illusion?

She seemed ready to walk on and leave us alone, but the dude strode right into our camp. He had the look of a juggalo without face paint, a wiry, gangly guy with thick glasses and close-cropped, 1/8-inch hair that was bright orange. He squatted right next to us, warming his hands by the fire, and I could feel our collective hair stand up.

"Come on, Tay," the girl said, "they don't want any extra company."

Tay?

The girl seemed nice. She said she was from Warren, and was now working double-shifts to get by at the McDonald's in Mio. Her friend Tay, however, disclosed little. When he finally spoke, it was with slack-jawed enunciation.

"Aww, man," he said, "that far feels goood."

"He's a little ..." the girl said, hinting at Tay's complete lack of boundaries.

"My nam's Tay," he said, reaching out to Cherry and giving a weird, limp handshake. Cherry was visibly disgusted, and later said Tay's hands were sticky; he described the stickiness as that of somebody who had spent hours taking apart cigarettes and rerolling them. We all stared at Tay, and he didn't venture another handshake.

He eyed Fournier's bottle of Woodchuck Cider hungrily. He spoke again, "Aww, man, Woodchuck. Tha' shit'll get you fuuucked uuup!" No doubt our Jugga-friend wanted some of our hard cider. We stared at him impassively.

"Come on, Tay. They don't want to be bothered."

Still he had to try. "Can I get one a' them —"

Before he could finish the sentence, Fournier and Cherry simultaneously barked, "No!"

He stood there, staring at us, licking his chapped, split lips and staring at our drinks, our coolers, our camp.

"Tay! Come on! Let's go!" the girl cried.

"You guys wanna know the weather?" he said.

We just stared at him. He fiddled with his phone for a minute or two, pressing buttons and looking confused.

"Thunderstorms all night," he finally said.

We said nothing. The radio had not predicted thunderstorms at all. We figured he was just sore about not getting "fuuucked uuup" on our Woodchuck.

After more urging from the woman with the now-restless dog, Tay finally stopped standing there and wandered off behind her, his lanky, pale form at last disappearing down the trail. Cherry got up to wash off his sticky hand. Little by little, the precious illusion of being away from it all returned to our camp.