No filmmaker I can think of had a better past year-and-change than Ryûsuke Hamaguchi, an enviable feat in our stricken time. The director and co-writer of Drive My Car, co-writer of the sublime Hitchcockian thriller Wife of a Spy, and solo writer-director of Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy’s done more and better work through a pandemic than most could manage in a regular decade. With a recent suite of work proving not only deft and sturdy but frequently transcendent, Hamaguchi has displayed an appetite for experimentation across a range of genres, themes, and tones.

Where the newly Oscar-winning Drive My Car grappled with the weight of loss, cutting between rehearsals and what could often feel like periods of recovery in between with a severe, even curt editorial hand, Wheel — which plays at the Detroit Film Theatre this Sunday — bears its burdens more lightly. Set up as a triptych whose vignettes cross-pollinate in terms of romantic themes, the film tells dense, literary, and quite modern stories of characters teetering between extremes of longing and hurt, disarming viewers to their workings with a remarkably airy style.

Indebted plainly to the most questing, good-humored, and circumspect works of Éric Rohmer, Wheel feels buoyed no matter where its stories go by its light and graceful form. As with Rohmer’s first prolific decades of material, Hamaguchi treats the existential through bright windows into the everyday. Using minimal resources in terms of cast and setting — some three speaking parts per segment, populating easily available shooting spaces like cars, offices, transit systems, and domestic interiors — Hamaguchi’s work here feels purposefully stripped-down, forsaking showiness in a manner that flatters his own craft.

Driven by honed, extended scenes (some easily surpassing twenty minutes) driven solely by dialogue, framing, and performance, the modesty and sense of “dailiness” of each segment’s apparent subjects belie their ability to touch on deeper themes. Take, for instance, the film’s first episode, which opens with Meiko, a plainspoken fashion model (Kotone Furukawa), and her starry-eyed friend, Tsugumi (Hyunri), departing a shoot where they’ve just worked together. Throughout a meandering car ride, Tsugumi opens up to Meiko about a thrilling date she’s had recently with a man who’s expressed to her both his desires for her and a painful romantic history that’s left him hesitant to move forward with her. The conversation, like many in Wheel, dances on the boundary that these sorts of conversations tend to occupy: an overlapping space between the trivial, the real, and the monumental. As much as these sorts of romantic musings could be taken for gossipy nothings (a gendered notion, for what it’s worth), relations that accrue gravity so often begin in just this way. Framing these first glimmers as the subject of breathless, hopeful remarks, the conversation (approached lightly though it is) accrues both a sense of the credible and a potential for import. For it’s a peculiar combination of feelings, this same strain of hope or faith among them, that makes successful romances the life-altering things they are.

But over the course of the two friends’ talk, confident-seeming Meiko largely adopts the pose of a listener, patiently plying her eager friend for details. Without spoiling too much, I’ll stop at saying she’s hiding something, and that these sort of furtive dynamics undergird the vision of relationships Hamaguchi promulgates across each chapter. Rarely in Wheel are both parties truly open, and so it goes in most first and early meetings. Such negotiations form the bedrock of friendly and romantic intimacy — acts of cautiously opening up, always at some risk. They’re reliant, too, on the presumptive leap that you can trust and know another person as you’d hope.

Such guarded dynamics bleed into the second episode, which sees an adult university student, Nao (Katsuki Mori), attempting to seduce her French professor, also a prominent novelist — all at the whims of a casual, on-the-side romantic partner who’s struggled in his course. If that premise sounds juicy or overly courant, it’s approached with an evenhandedness that characterizes all three episodes. Throughout the work, Hamaguchi keeps a steady distance, allowing for an equitable engagement by the viewer with each of the characters in play. Avoiding a moralizing air even when characters (like Nao’s partner) are at their worst, Wheel embraces the presence of chance and accident as forces that shape its characters’ lives. Freed in this way, he observes the professor’s guarded engagement with Nao’s roundabout advances calmly, treating a fraught situation with a welcome air of reserve. Though hierarchies of both status and information impose themselves on the dynamic, in Hamaguchi’s treatment, these don’t preclude either party’s capacity to move the other emotionally, regardless of where what follows from that may lead.

Such power structures (save for a whiff of class) are fairly absent in the last episode of Wheel’s three, which treats two characters who run into each other around a high school reunion. Recalling each other only vaguely, the two women fumble their way through a chance meeting on an escalator, disarmed by faulty attempts at recollection and the wear of years in isolation. In a slippery segment whose terrain is continually upended, structures and both first and recalled impressions seem to fall away, re-casting each person as, at least for a blissful moment, new. In this light, their engagement becomes not about old scores but freeing escapes, and the things they might give one another.

Through this halting but never cloying approach to depicting interpersonal connection, Hamaguchi melds an air, or atmosphere, of small diversions with feelings (and sometimes stakes) that are as big as they come. Despite its sense of modesty, Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy feels by its finish anything but slight; on the contrary, it’s a rich, essential, and wholly pleasurable burst of life in a medium and realist genre that could use many more like it. But part of the film’s pleasure surely stems from the scarcity of what it offers, giving it the same air of delicate value as any of its chance meetings.

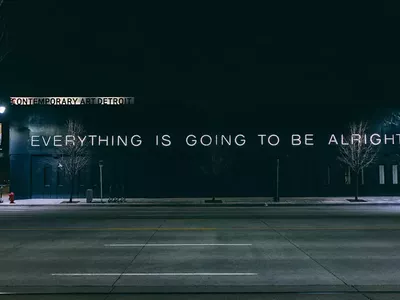

Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy will be screened at 2 p.m. on Sunday, April 10 at the Detroit Film Theatre; 5200 Woodward Ave., Detroit; 313-833-7900; dia.org. Tickets are $9.50 general admission, $7.50 for seniors and DIA members.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, or TikTok.