Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

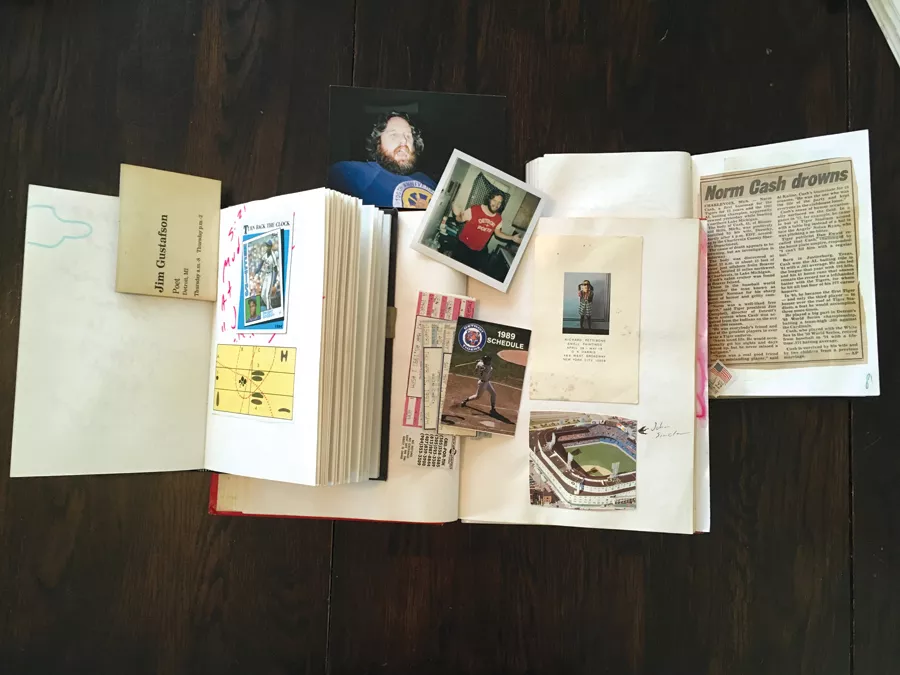

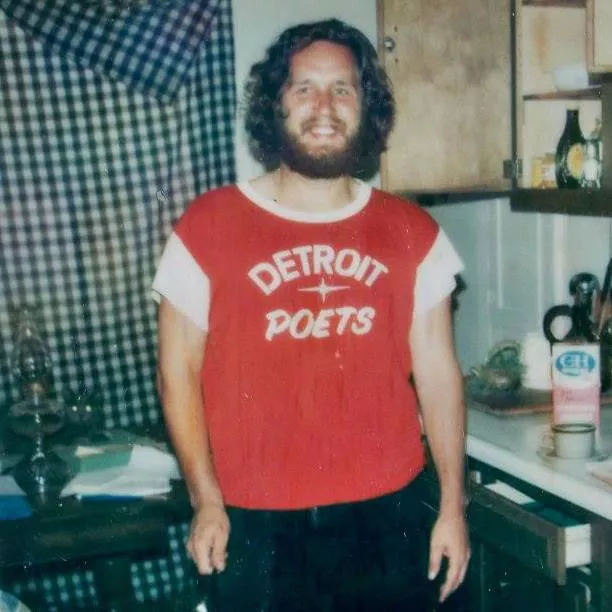

Boisterous local poet Jim Gustafson saw his last Tigers game 20 years ago. It would have been at Tiger Stadium in 1996, the year he died. Had he lived longer he probably would have made it over to Comerica Park — even though he published rants criticizing it. In a February 1994 letter to the Detroit Free Press he defended the old ballpark against proposals for a fancy new stadium. The poet was a populist — an anti-snob.

Gustafson loved attending and listening to ballgames. (Full disclosure: Gustafson was the author's uncle.) From the late '60s til his death, Gustafson wrote a lot about Detroit: about virtue and want, sex and rock 'n' roll — and yes, about baseball. The sport is a theme in his poetry, which was published in five books and featured in magazines ranging from Rolling Stone to the Paris Review.

He drew pictures of fields and players in his writing notebooks, in between notes and drafts of poems, sometimes at home by the radio, sometimes up in the Bleacher Creature-era cheap seats of Tiger Stadium with a community of Cass Corridor writers, artists, and musicians.

Surely Gustafson dreamed about making the sports pages when he was a kid in Pontiac and Waterford.

His sister, Kathy Codere, remembers him as a kid: "always watching sports, reading about sports, collecting baseball cards."

Did Gustafson play ball? Maybe in the neighborhood. But his lazy eye gave him limited depth perception. He was thickly built and clumsy, kind of an indoor kid.

"I can still see him, at 10, 11, 12, when we still lived at our other house," Codere says. "On a hot summer afternoon I'd be at the beach, he'd be laying in his underwear, in his little tighty-whities, eating chips, reading comics, and listening to the ballgame."

In high school, he slimmed down and rebelled. He aged out of Saint Benedict's and attended public schools where he grew out his hair. An anti-war teacher was resonating with the students.

"He went from quiet," and memorizing stats, "to having a cool, almost rock star status in high school," Codere says. "It seemed like everybody knew him."

He went to Canada, stayed in London, and visited Spain. When the Vietnam War ended and he came back to the United States he became less interested in studying stats and more interested in the rhythm and logic of baseball — not just the game in the stadium, but playing with words on the page, too.

His poems make it clear, how easily he thought of life as a ballgame. He may have not been an athlete. Poet-activist John Sinclair said he was "out of control. Nothing like an athlete." But Gustafson was ambitious about his writing. He could pitch some of the biggest stories in town. In the right conditions it seemed his fast talk clocked in at over 90 mph.

In "Baseball Sonnet," probably written in the '90s, he wrote:

You hit the dirt like a misbehaving angel dumped

from a traffic helicopter. So brush yourself off,

find your lucky cap, hitting, not thinking, and

get back in the box. Only you can make the decision

when to quit being a perpetual rookie

and get on with the humongous business of becoming a hero.

He was not a stay-at-home poet. He wanted experiences, away games. He wrote about his adventures, and his adventures took him all over.

He would live in other cities — in Albuquerque, N.M., and San Francisco, in the small, artsy community of Bolinas, Calif., where he and poet and Basketball Diaries author Jim Carroll were roommates. Closer to home, he lived in Chicago's North Side. Living in the land of the Giants and the Cubs, he caught games in other stadiums.

But he always came home to Detroit, and he always rooted for the Tigers.

Cass Corridor pickup games

Around the same time that the Tigers won the 1968 World Series, Gustafson was spending more time in Detroit, with artists and other writers in the Cass Corridor. Now he followed arts gossip as closely as players' stats, submitting his poetry to the literary magazines with all the hope with which a collector opens a pack of baseball cards.

During this time, Gustafson played in pickup games in the Cass Corridor. "We played baseball and football," says Alternative Press publisher, poet, and Gustafson's literary executor, Ken Mikolowski. "Just having fun, a lot of beer, a lot of laughs."

Mikolowski remembers pitching softballs in "Just Artists Against Poets" pickup games, on a team with other city writers like Mick Vranich, Archie Anderson, and Bob Andrews.

He says the poets challenged artists like John Piet and Bob Sestok, and Gustafson's close friend, painter Bradley Jones.

"The artists and poets, we all mixed," Piet says. "There wasn't a regular practice, but you get a bunch of guys and girls together and play a game."

"The artists almost always won, because they'd have these big, strong sculptors against us and our typewriter fingers," Mikolowski says.

"I don't remember it that way," Piet says. "I only remember it as fun."

Opening Day

Best known for his much-anthologized poem "The Idea of Detroit" and, fittingly, one called "No Money in Art," Gustafson never made much money with poems. He kept afloat selling reviews and articles to magazines and newspapers, including this one.

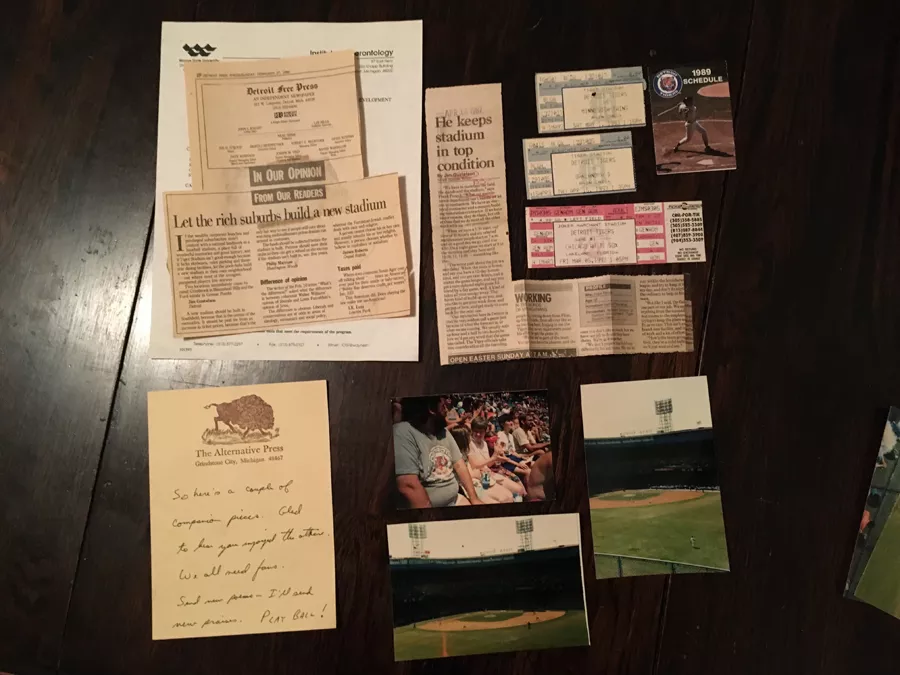

In April 1989, in the rowdy era of the Bleacher Creatures, Gustafson wrote a love note about Opening Day for the Metro Times.

In the essay, he criticizes then-Tigers owner Tom Monaghan's "avarice." Yet most of Gustafson's essay focuses on his excitement, his love of the schedules, the ritual, the anticipation.

"On Opening Day itself, the troops rise early, carefully pack their party rations and congregate on Kaline and Cochran Drives, coming from Canton, Canada, and Kalamazoo, to drink a brew or two and rise to the appropriate level of spring-how-do-you-do-yahooism."

The springtime excitement dated back to his childhood. "It was a big deal," Codere says. "Our mom and dad would always let him stay home from school to watch the game on opening day," Codere says. "He got good grades, so it was a special treat."

As for why he loved the game itself, he wrote, "It doesn't take long to remember why baseball is such a wondrous creation, the sport that most resembles art, the sport that best mimics life."

After the Tigers won that year's opener 10-3, he called the game "a neat package of grace and order on the field, and chaos and commotion ... certainly little creature comfort, at least in the bleachers."

Poetry and baseball

Following a 1994 discussion about building a new baseball stadium, Gustafson sent an angry letter to the Detroit Free Press:

"If the wealthy corporate honchos and privileged suburbanites aren't content with a national landmark as a baseball stadium, a place full of wonderful memories and great history, and if Tiger Stadium isn't good enough because it lacks skyboxes, valet parking, and three-star dining facilities, let the pooh-bahs build a new stadium in their own neighborhood — out where most of the arrogant, pampered players live anyway."

Gustafson hated the idea that baseball might become inaccessible to the fans. At Tiger Stadium, according to Mikolowski, they had used to catch games in the upper center field, no shade, for 75 cents a seat. The price gradually increased to $3.

"We had good times," Mikolowski says. The first time he met Gustafson's girlfriend, Eileen Bobrycki, was at a baseball game: center field bleachers, upper deck. "All the poets, we loved the ballgame. We all loved crime novels and baseball."

Mikolowski remembers poets and other heroes of the arts in Detroit. "Jim and me and John Sinclair, Glen Mannisto, Faye Kicknosway, Johnny Evans from Howling Diablos, sometimes Ann (Mikolowski, painter, married to Ken) would go," he says. "We'd sit in the lower right-field bleachers — still cheap but in the shade."

They'd sit behind Kirk Gibson. The poet and the Southpaw outfielder shared a hometown, though Gustafson was a decade older. They'd yell at Gibson, and sometimes he'd yell back.

Gustafson was a known heckler at poetry readings too. "Jim was a disgusting heckler at other people's readings," Sinclair says. "I don't know about at the ballpark as I never attended a game with him but I saw him in drunken action at many poetry and art events."

Sinclair says Gustafson "was a terrible alcoholic who reveled in public drunkenness, which never struck me as cute or even socially acceptable," he says. "Frankly, I thought of his public persona as Jim Disgustafson."

So in life and at Tigers games, Gustafson with his demons kept it somewhere between real and real rude.

Take his poem "Poetry and Baseball," from his unpublished 1996 manuscript called "Virtue: Heartbreak and Resurrection." In this section of the poem, he wrote autobiographically:

A couple of early reports called me "uncoachable,"

and I took this to be high praise,

and kept playing the game my way.

I had no intention of laying off the high, hard one.

I believe that swinging from the shoetops

and feeling the energy surge up my strong legs

and through the muscles of my unburdened back

was a paramount joy of the game.

If I hit the ball once in awhile,

that was a real bonus.

One can only guess what he'd think of Comerica Park — of all the corporate affiliations, the lack of history, the lack of trough urinals, where the tickets cost much more than $3.

There's a pretty good chance he'd get over his disdain of the commercial aspects — as long as he could find a beer and a cheap seat in the sun with his friends to root for the home team.

Meredith Counts is co-editing (with Ken Mikolowski and Michelle Perron) a book of the poetry of Jim Gustafson. She maintains a Facebook page about Jim and his archive: facebook.com/JimGustafsonPoet. Poems by Gustafson, Mikolowski, and Sinclair will appear in a 2018 anthology, I Just Wanna Testify: Poems about Detroit's Music, edited by M.L. Liebler and Jim Daniels, to be published by the Michigan State University Press.