In Detroit, a poetry workshop gives high school students freedom to be themselves

Burning their fires for all to see

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

After munching on rectangular slices of Pie Sci Pizza, the high schoolers sit behind long, wooden tables as the poet laureate of Michigan glides across a dimly lit room inside the Scarab Club in Detroit, keen to deliver lessons on a cultural tradition so ancient it predates the birth of Christ by more than two millennia.

Within the next intimate hours, Nandi Comer, 44, teaches poetry while battling a sinus infection that isn’t contagious. Sporting stylish glasses, whip-like braids, and a youthful attitude, she passes out poems written by people who aren’t dead. “If they’re in town, you can talk to them,” she says.

The time spent together on a recent gloomy Saturday in November is a far cry from an after school punishment. The workshop is part of nonprofit InsideOut Literary Arts’s Visiting Writers Series, where teenagers participating in the Citywide Poets program can think critically, build self-confidence, express themselves without threat of censorship, and improve their craft together as they excavate meanings behind verses and liberate the poets within.

The group of 18 teenagers, a mix of writers and spoken-word performers, choose to be here. The voices of some, already found. In a dark and divided world, they combat negative stereotypes. They seek to restore. The poets will soon illuminate their truths. An open mic is scheduled later in the downstairs art gallery.

Right now, life is full of rough drafts, but they don’t seem to be afraid of them.

The young are still dreaming. Their better angels resound.

A little after 12:30 p.m. the workshop begins. The faint glows emanating from stubby and geometric chandeliers reveal a chiaroscuro of bodies veiled by shadows. Comer encourages the students to scribble their twinkles of thought onto the stark-white computer paper as they dive into the first poem. Comer provides questions that prompt thinking amid the quiet communion.

What makes you question?

What puts a little spark in you?

What makes you feel?

A young girl reads aloud “The Colonel'' written by Carolyn Forché in the late ’70s. The legendary poem recounts a disturbing dinner with a military officer from El Salvador, according to Dissent Magazine. The Central American country’s civil war would last from 1979 to 1992.

A poet, teacher, and activist, Forché was born in Detroit and widely credited for coining the phrase “poetry of witness,” which describes the lineage of English language bards who’ve entered battlefields, endured exile, observed suffering, even evaded death to inscribe what they survived for the people to behold, process, ponder, and where the political and personal collide.

On the page, the poem is a thick, single stanza of text.

The first line foreshadows the telling of a tale. What you have heard is true.

The girl recites calmly the images of destruction. Broken bottles were embedded in the walls around the house to scoop the kneecaps from a man’s legs or cut his hands to lace.

The images of mutilation. He spilled many human ears on the table. They were like dried peach halves.

The final lines hit chilling notes.

Some of the ears on the floor caught this scrap of his voice. Some of the ears on the floor were pressed to the ground.

The reading ends. The students snap their fingers, a gesture signifying appreciation for what they’ve just heard and absorbed. A soft, pattering sound. Snap. Snap. Snap.

Now it’s time to unpack what it all could mean.

Deciphering poems has become routine, but each one is different. There are really no wrong answers. Imaginations can run wild around here. The interpretations start flowing out of some like water surging from an open fire hydrant.

“What did it for you?” Comer asks the group of high schoolers.

“The human ears and the dried peach halves,” one young boy says, beginning to unspool the tensions embedded in the verse.

“This comparison between luxury and cruelty is something I noticed.”

“Yeah, you got it. You’re onto something,” Comer responds.

Together, they mine the language for more meaning and technique, singling out lines that grip their curiosities. The dimly lit room quickly transforms into a bazaar of drifting theories and revelations.

The wife in the poem couldn’t sustain her life under a violent regime, so her act of resistance was to leave.

The images of the moon swung bare on its black cord and my friend said to me with his eyes: say nothing were cinematic moments another young girl had never encountered before.

“I didn’t think about that. But people do say a lot of stuff just with their eyes and their expressions,” she says of her discovery.

Comer is intrigued by the answers harvested by the students then pivots to the reason why she keeps returning to “The Colonel.”

“I keep trying to figure out why? Why does it resonate so much with me? And it is the beginning sentence and the last two sentences,” she says.

“It starts with talking about hearing and ends with the hearing of these dead people.”

She launches into her own analysis. Those words made her think about the ways people hear. Those ears could be refusing to listen or self-aware. Forché deploys unique turns of phrase, avoiding the brute force of literalism and clichés.

Comer hopes the workshop will give the students more tools to use in their own work and expose them to the role of poets in communities across the ages. In some traditions, poets are called griots.

The literary genre is shifting in the popular consciousness, being more democratic rather than institutionalized while bonding the storytelling species together.

“We call on poets during our most difficult times, during the most celebrated times. There’s always the poet reading at a wedding, at an inauguration, at a funeral,” Comer says.

“So I think we know that we understand the importance of poetry. I think that social media has made it much more accessible.”

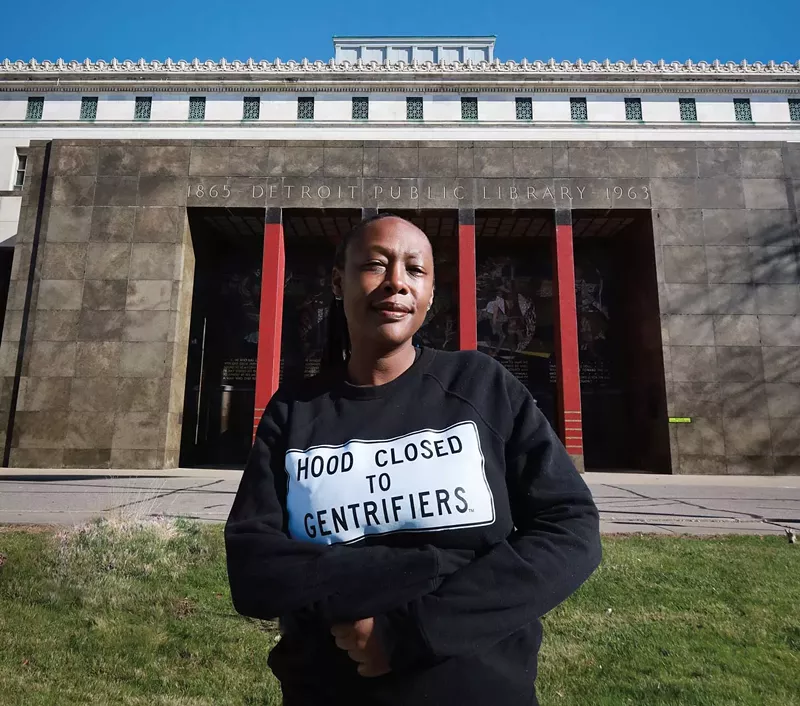

Ever since she was named the poet laureate in the spring, the second ever in the history of the Great Lakes State, it’s already been a whirlwind for Comer, several months into her two-year term. “It’s been really amazing,” she says.

She’s visited public schools and libraries. She recently traveled to St. Ignace in the Upper Peninsula for a reading. Outside of her laureate duties, she collaborated with a wrestling company to orchestrate bouts with poems. In her recent poetry collection Tapping Out, Mexican freestyle wrestling is the primary lyrical motif.

“All in all, I’m just really an advocate for the art form and showing people how poetry can show up in their lives,” she says.

Today’s a bit of a homecoming for Comer, describing herself as an “InsideOut baby” once taught by the organization’s founder Terry Blackhawk, an accomplished poet in her own right.

On her website, Blackhawk says her childhood was a “sort of moveable feast” with barely any money but lots of culture. Her father was an education professor who often traveled. Her mother, a pianist. The piano moved wherever the family moved.

Next to her short biography is a portrait of Blackhawk, eyes gazing upward looking placid and inquisitive.

As a teacher, Blackhawk believed in the gift of poetry. She invited professional writers to her classroom, an instructional model she infused into the literary nonprofit she founded in 1995. She lit a match inside a young Comer, then a student at Communication and Media Arts High School. She asked Comer to join her creative writing class. She showed Comer the craft of poetry and the publishing world.

She wanted students to expand their minds, to be creative, to be brave.

“She retired to dedicate her life, all the time to InsideOut,” Comer says, once serving as the Writer-in-Residence for the organization. “Today, it’s an incredible, robust program.”

Halfway through the workshop, the high schoolers then delve into more poems chronicling the traumas of war and colonization, including Iraqi American poet Dunya Mikhail’s “The War Works Hard.”

Mikhail was a translator and a journalist for the Baghdad Observer and then got put on Saddam Hussein’s enemies list, according to The Poetry Foundation. After immigrating to the United States in the mid-’90s, she’d eventually earn a master’s degree at Wayne State University.

Mikhail’s poetry is known for “irony and subversive simplicity,” evidenced by the punchy opening lines.

How magnificent the war is!

How eager

and efficient!

The students isolate the poem’s techniques.

The enjambment and the way the lines cut off so sharply and abruptly.

The personification of the war.

Jassmine Parks’s long, lavender braids cascade down her shoulders. Once a local slam poetry champion, she often chimes in to affirm the students’ interpretations, interrupting short stretches of quiet.

All of the students here have joined Citywide Poets, an after school program offering weekly writing workshops taught by professional artists as well as performance and publishing opportunities. They also offer an annual scholarship covering college tuition for up to $25,000 a year for up to four years. High school seniors participating in the program are eligible to apply. Over 100 high school students from across metro Detroit are enrolled in Citywide Poets for the 2023-24 academic year.

As the organization’s program development coordinator, Parks helps oversee the program and designs workshops in lock step with the youth wherever they happen. From the libraries to the schools, the youth help build the learning culture inside those “sacred” walls.

Where empathy and connection and independence can grow.

“They can explore their own identity and their own worldview. And I think that’s what's freeing about this because they're coming into their own. This is a pivotal age where young people are separating their identity from their families and trying to decide who they're going to be, who they are,” Parks says. “Thank God we don’t live in Florida. These conversations would get cut off at the knees.”

Between readings, the students write down singular moments etched in their memories for a brainstorm exercise. Ones where they witnessed the unjust, the unfair unfold before them.

The students reenact the chaotic scenes by accentuating the syllables. Their voices, rising.

The shock of an attempted car break-in during Halloween.

“And I was like, ‘Oh my god! Hey! I think they’re breaking into your car!’ And she was like, ‘What?!’ And so, my cousin, my dad, and my brother all ran outside. And you know, it ended the way it ended.”

A high school freshman, vainglorious and unapologetic, ripping the head off a friend’s teddy bear during lunch then disposing of the mangled stuffed animal.

“Like she put her back into it. She threw it in the TRASH!”

These incidents show the surreality of being young. The students then write unvarnished verses in a stream-of-consciousness style, each packing a wallop of vulnerability.

and I wonder if my cousin when she gets her window replaced again

will make art of what was almost taken from her

I saw the eyes of a teen, an adult, a child then nothing

Snap. Snap. Snap.

Charisma Holly, a junior at Detroit Edison Public School Academy, is an archetype of a bubbly teenager. She stirs to life when she lets her words flow. A sunshine of a smile born from the diaphragm.

Her online scrolling sparked a metamorphosis.

Charisma fell in love with poetry after watching videos of the American spoken-word poet Rudy Francisco on the Button Poetry YouTube channel.

Across his videos, he speaks into a microphone, performing poems that tackle the stickiness of healing and forgiveness and revenge and the quirkiness of giving bad hugs and liking ginger ale.

His voice, loud and billowing. His cadence, moving faster and faster like a bullet train.

“I felt so inspired by watching him go and perform,” Charisma says. “And it made me think, like, ‘I have something important to say!’ I have a story that I want to tell. And I want to tell it in a way that will make other people want to tell stories.”

Since joining Citywide Poets, she’s shared her original poetry at local art museums as part of a performance troupe and gotten paid for it. She’s also complemented her creative resume with other titles in addition to poet. An actor. A backstage technician. Her poetry touches on the light and dark in life, believing the worst things that happen doesn’t define a person forever.

Her words, a lighthouse for better tomorrows.

“Given the state of the world, I always say, poetry won’t end wars. Poetry probably won’t end hunger. Poetry probably won’t reform the school system,” Charisma says, smiling through the end of her answer. “But it’ll give somebody enough hope, enough joy, enough inspiration.”

The workshop ends after 2 p.m. Comer, Parks, and the students scurry down the steps for the open mic in the art gallery downstairs.

The young poets don’t need a microphone. Their voices echo inside the gallery walls adorned with sculptures resembling wounded violins. The shadows no longer cloak them, instead baptized by bright lights.

One by one, the students approach the front of the room filled with more than a dozen people seated in dark folding chairs.

For some, smartphones are the tablets from which they read testimonials and confessions to past, present, future. The ballads of sorrow spoken in miniature. The clarion calls. The warning shots.

One by one, they speak truth to poetry.

because a child can’t tell their parents they’re queer until they have their

bags packed and ready in case they are erased

please try and get to know me. can you put that pride aside?

they lay their eggs in my open stomach

you can never be too safe

I know what it’s like feeling like there’s nowhere else to go. world up in a tornado

they don’t have to grow up as fast

what is it about you that makes it so hard to hate you? i want to hate you and i can’t and i don’t know why. mom, will you pick up the phone, please?

will they suffocate you and destroy you?

he seen the power of the pencil over the power of the pistol

there is something wrong here there is something wrong here there is something wrong here

her message is as predictable as the tone of her voice

the world never changes inside this sanctuary

we wanna live longer than the sun

Then comes fluttering applause. Flashing hums of recognition.

“Given the state of the world, I always say, poetry won’t end wars. ... But it’ll give somebody enough hope, enough joy, enough inspiration.”

tweet this

The headliner this afternoon is Comer. Sitting in the back row, Erin Pineda, a co-owner of independent bookstore 27th Letter Books, has brought copies of Comer’s poetry collections Tapping Out and American Family: A Syndrome to sell. All of the workshop students got these books for free. Comer now reads her poetry before the audience.

She is no longer the teacher but the bard from the west side.

She recites a poem about Malice Green, a 35-year-old Black man who was beaten to death by Detroit police officers in 1992, a few months after an uprising swept across the streets of Los Angeles in the wake of Rodney King getting beaten by police. Green’s death rocked the community and the nation.

She recites a poem about her hometown and its forgotten people and places. Her words hit like gospel truth. What do you feel like people get wrong when they try to tell stories about Detroit? Everything.

KeAnna Mills, a junior at Thurston High School in Redford, is measured and calm. She writes poems about school and basketball. She plans on majoring in English or journalism once she goes to college.

InsideOut helps the rookie poet boost her writing skills and offers an avenue to explore new genres of life, to dream big.

“It’s like giving people ways to express themselves in other forms that they didn’t know was possible. It’s really good for me,” she says. “I’ve met people that I wouldn’t have been able to meet anywhere else.”

For the teenager, poetry isn’t reserved for people with literary ambition. It’s a tool to learn. A hobby. A way to pass the time that doesn’t harm other people.

Her workshop peers had just shared a piece of themselves to personal champions and strangers inside an art gallery. The stories they chose to tell uncorrupted by critique. The stories that send a message beyond heartache and angst and hope woven together.

Fragments of young life that feel real and honest and true.

“It’s time for everyone to see that Detroit youth, specifically Black youth, can do something good too,” KeAnna says, her impromptu passion soaring from her tiny frame like a phoenix.

“It’s always, ‘Oh, look at what the Black kids are doing. They aren’t even doing anything. They just go into drugs, and they’re getting locked up.’ This is a great way to show that we can do something good too! We always have been. This isn’t news.”

Around 3:30 p.m. the open mic ends. The crowd slowly disperses until the gallery is close to empty. The people exit the tall brick building, welcomed by orange leaves waving above the side street, a sign of autumn in full swing. A season of change.

An afternoon of bearing witness is over until next time, led by a young generation of poets. Torchbearers of an ancient tradition blazing forward. Burning their fires for all to see.

Subscribe to Metro Times newsletters.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter