Although now dead for nearly 50 years — she expired in 1976 at age 85 — Agatha Christie remains as mysteriously ubiquitous as ever. Rivaled in sales only by William Shakespeare — and let’s acknowledge that he received a 330-year head start — Christie has conservatively moved more than 2 billion books since The Mysterious Affair at Styles, her 1920 debut. And the tally continues its dizzying rise: With her work available in more than 100 languages — she’s also considered the world’s most translated author — Christie still manages to sell as many as 5 million books annually.

Exactly why Christie exerts such an inexorable magnetic pull on readers isn’t easily explained, but the combination of her dialogue-heavy, easily grasped prose, elaborately baroque plots, and comfortably familiar recurrent characters (Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple most prominently) ensnare fans with the same capture-and-keep efficiency as a mousetrap. (The Mousetrap, of course, is her most famous play, whose epic West End run — history’s longest — began in 1958 and could only be halted by the onset of a worldwide pandemic. Further attesting to Christie’s persistent cultural relevance, a production of The Mousetrap makes its long-delayed Broadway debut later this year.)

Although largely immune to the allure of mysteries, I confess my own grade-school infatuation with Christie, a sort of literary puppy love: She was among the first writers whose other work I consciously sought out after reading one of her novels. But after imbibing Christie’s pleasant English tea for a few books, I soon desired stronger stuff. Since those youthful days, I’ve largely ignored Dame Agatha, with the exception of Sidney Lumet’s entertaining Murder on the Orient Express in 1974.

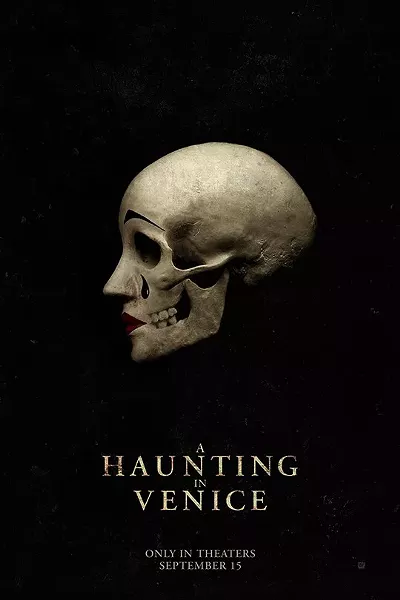

Which at last brings us, with appropriately Christie-like scene-setting deliberateness and indirection, to Kenneth Branagh’s A Haunting in Venice. The third of Branagh’s Christie adaptations — following his 2017 Murder on the Orient Express and last year’s Death on the Nile — Haunting follows the template established by its predecessors: sprawling boldface-name cast, exotic locale, plush production values, flamboyant visuals. As before, Branagh himself stars as the famed, elaborately mustachioed Belgian detective Hercule Poirot, here retired to post-World War II Venice and striving to avoid any further entanglements in murderous doings.

But, inevitably, someone coaxes Poirot from seclusion and back into the game: Mystery writer Ariadne Oliver (Tina Fey) manages to lure her old friend into accompanying her to a children’s Halloween party and — the true bait — a post-soiree séance at the decaying and allegedly ghost-ridden palazzo of bereaved opera singer Rowena Drake (Yellowstone’s Kelly Reilly). Rowena has secured occultist Mrs. Reynolds (the post-Oscar Michelle Yeoh) to conjure the spirit of her recently drowned daughter, Alicia (Rowan Robinson), an apparent suicide. Among the other participants gathered to summon Alicia: her caddish former fiancé (Kyle Allen), her physician (Jamie Dornan) and his intellectually precocious young son (Jude Hill), Rowena’s ex-nun housekeeper (Call My Agent’s Camille Cottin), and Poirot’s bodyguard (Richard Scamarcio).

Angling for a bestseller after a string of commercial disappointments, Ariadne hopes Poirot will help supply some raw material by debunking Mrs. Reynolds’ supernatural powers. He initially seems to deliver by quickly uncovering the spiritualist’s hidden assistants, a Roma brother and sister (Ali Khan and Emma Laird). But odd, inexplicable occurrences continue even after the pair’s discovery, and then the film’s first body quite literally drops. As a fierce storm descends on Venice, roiling the waters of the city’s canals and trapping the séance-goers in the palazzo, Poirot must both ferret out the killer and grapple with increasing self-doubt about his rationalist worldview: Perhaps this house truly is haunted.

Christie completists puzzled by their failure to recognize the film’s plot needn’t fret. Although A Haunting in Venice purportedly adapts her late-career Hallowe’en Night (1969), the filmmakers use so little of the novel that it’s essentially a wholly original work. Branagh and screenwriter Michael Green — his collaborator on all three Christie films — not only move the action from the English countryside to Venice, they add the supernatural theme, invent an entirely new set of characters, and retain only the faintest hint of the story (both film and book feature an attack when bobbing for apples, but the movie swaps in Poirot as the victim). For the most part, those wholesale changes are all to the good: Hallowe’en Night is a dull, convoluted slog, though Christie legitimately startles with her decision to dispatch not one but two children, and without even modest sympathy.

Unfortunately for Branagh, his Christie films suffer a bit by comparison with Rian Johnson’s more sprightly, satiric Knives Out whodunits, in which Daniel Craig’s comically droll Benoit Blanc proves a far more winning detective than the dour Poirot, whose depressive aspect is overemphasized in these recent adaptations (even his creator eventually found Poirot something of an egotistic bore). It’s also mildly disappointing to see Branagh again retreat to safe commercial ground after his deserved success with the semi-autobiographical Belfast, in which Dornan and Hill also play father and son but in a much more realistic and affecting manner.

Still, Branagh’s old-fashioned approach to Christie undeniably matches the sensibility of the author, and Haunting provides a large measure of pleasure, including Fey’s wry take on Christie’s Dr. Watson-style self-portrait, Hill’s budding Poirot in miniature, and the expressionistic brio of cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos’ fisheye lenses and Dutch angles.

Like Christie’s novels, A Haunting in Venice qualifies more as comfort food than haute cuisine, but sometimes a shepherd’s pie nicely satisfies.

Subscribe to Metro Times newsletters.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter