Two attractive multistory murals went up in downtown Ann Arbor in 2015, when real estate groups sponsored projects as cheerful and celebratory as you’d expect. Yet a 2016 project may be the most significant downtown mural, while showcasing the contradictions of the “community mural” medium.

I was shopping for 1960s paperback adventure novels for my Jamaican grand-nephew when I first saw the African American mural taking shape on the parking lot at Ann and Fourth streets, painted by Steve Coron’s Community High School students, whom a June 17 MLive story listed as Olivia Comai, Chloe Di Blassio, and Ajay Walker.

Mayor Albert Wheeler is painted much younger than he looked during his 1970s administration, perhaps represented at the start of his University of Michigan teaching career. Public transportation administrator Richard D. Blake and wife Rosemarion are painted as a couple, but Mayor Al Wheeler is some distance from wife Emma, housing activist and longtime local NAACP president. The Dunbar Community Center stands proudly, but, ouch! — the tip of the African Methodist Episcopal church’s spire is nipped off.

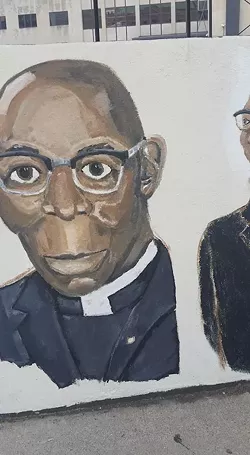

There’s a dignified rendering of that church’s Rev. John A. Woods, and my identification of these personages was aided by Facebook friends of his son, a fellow Ann Arbor Pioneer High ’73, shortly before Woods the younger attended the A.M.E. Church tri-centennial celebration in Philadelphia. There’s also a large well-modeled face of Rev. Carpenter of the Second Baptist Church. A cartoony, Keane-eyed, and croissant-eared barbecue chef DeLong stands beside a finely painted image of U-M music professor Willis Patterson, whose musical skills graced the First Congregational Church’s Sunday services to my late father’s enjoyment.

When I saw the wind blowing the white locks of a concerned Coleman Jewett, I couldn’t help but think of John Steuart Curry’s intense John Brown, and Jewett’s massive head dominates the smaller Emma Wheeler beside him. But the portrait has since been modified to show Jewett less alarmed-looking.

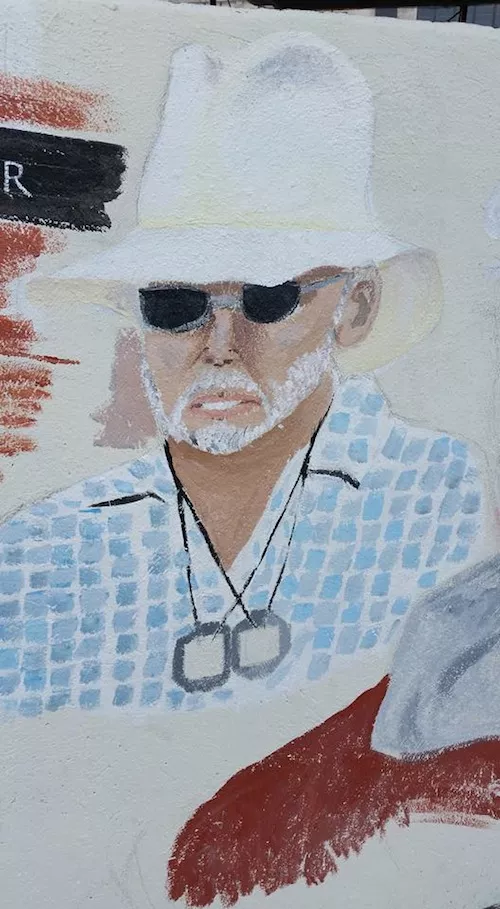

Brian Westfield peers out in sunglasses, a pair of dog tags beneath his big white straw hat. I didn’t recognize him, a Pioneer coach of long tenure, his very light complexion noticeable among the African Americans. I don’t know if he identified as black or not, but was chosen by the student painters for inclusion. Then it struck me: Someone of another race in any Ann Arbor context may be noticeable, but not a problem. And this might have been how black kids felt, a minority in Wines Elementary, Forsythe Junior High, and Pioneer High School when I attended. This mural is evidently about neighborhood, familiarity and community, not black nationalism.

Urban artwork always creates a dialogue with other works in the vicinity or public consciousness, and this is a good pendant to other local works in the heroic “big head” style around town. The popular Euro-American authors mural (one’s European, but he wrote a novel Amerika) on Liberty at State Streets, stylistically unified almost 40 years ago by a single artist’s hand, was commissioned by David Kotzube, who owned David’s Bookstore located above it. The most content-driven other big head mural, from a decade ago, depicts antiwar activists, though that fact isn’t apparent to a visitor on first viewing. Glimpsed on a downtown alley off Liberty, it’s as if they’d all ducked there to avoid police tear gas breaking up a demonstration (though the city seemed supportive of the anti-Iraq invasion marches I attended), or an array of their mug shots when arrested and booked.

My artist wife griped that such an important subject as Ann Arbor’s African Americans deserves the most professional possible treatment, yet as someone who began painting murals in high school I appreciate its educational experience. The collective action of painting a community mural together can enrich students’ lives the way playing team sports can. Artists, steeped in their unique visions, very much need to learn to co-operate with others.

The late muralist Jon Lockard (see Wayne State University’s Manoogian Student Center) made sure his students constructed solid, believable heads before focusing on features like mustaches and eyeglasses, a novice student’s inevitable tendency, shaped by cartooning. Some faces in this mural are so focused on small-brush surface detail, eyeglasses rather than a solid sculptural head to rest then upon, one wonders if it would have been better if this had been thrown up graffiti-style quickly, flat but less fussy.

The mural covers a low wall at the northeast corner of a parking lot. That student painters crouched or sat while painting probably discouraged them from backing up, changing perspective to look at their work in context of the whole. If there’s anything the fine “Diego and Frida” Detroit Institute of Arts show last year demonstrated, it’s that a mural shouldn’t try for the studied delicacy of a small Frida Kahlo canvas. But, however inappropriately applied, the students’ seriousness and desire for precision should be praised too. I wish the students had painted the background first, so the figures in foreground could expand as necessary into it. When I saw the unfinished murals, the nearly finished portraits were painted awash in a sea of white, which might be metaphorical for how many people of color feel in Ann Arbor.

There is the need for artwork that is most excellently crafted, by well-educated professionals who’ve earned their elite status, at the height of their powers. There is the counter need for democratization of the art-making process, the involvement of all stakeholders in the mural’s development and production, to avoid unappreciated “parachute art” imposed from above. These two antithetical currents resolve in each group-effort mural into a new, provisional synthesis. And the quest for something resembling democracy and inclusion in the otherwise singly directed art-making process, however elusive, is something that attracts many of us to the community mural medium.

I wonder if any student had suggested inclusion of Aura Rosser, shot by police in her home when they were called for a 2014 domestic disturbance, Ann Arbor’s contribution to the nationwide abuses highlighted by Black Lives Matter. Perhaps her unresolved (to many) shooting remains a better topic for a thousand sidewalk stencils.

The north end of Ann Arbor’s downtown once had a mural on an ecological theme, kicked off at a 1970s Earth Day, but to my knowledge this is the first celebrating African Americans active around there. Jon Lockard once joked that Ann Arbor’s idea of commemorating black history would be a bronze statue of street eccentric Shakey Jake. Yet the new bronze Adirondack chairs commemorating Coleman Jewett are an appropriate symbolic public artwork, and if they may need accompanying narrative of Jewett’s life and craft for them to be fully appreciated, comfy chairs in a public market (where he sold handmade chairs) are certainly a good place to hear local lore. The August death of Ann Arbor Public Schools music educator Louis Smith should kick off an Ann Arbor African American music mural too.

The mural on Fourth Street may be more about the neighborhood, once predominantly black, and personages seen there, than “black history” per se. A black academic once lamented in the Ann Arbor Observer how Ann Arbor was for the most part racially accepting, but within narrow class and professional boundaries, and how the closing of Keaton’s Recreation and other Ann Street establishments in the 1970s removed any trace of what was a significantly black entertainment district. This mural depicts notables from a minority community that is, though geographically beleaguered and dispersed by gentrification, still vital and unique in its long and many contributions to the salad bowl that is Ann Arbor.

Mike Mosher is professor of art and communication media administration at Saginaw Valley State University. His students’ community arts research mural work can be seen at www.svsu.edu/care. His personal consultancy site is communityartmachines.weebly.com .

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]