Diamond in the rough

Historic Hamtramck Stadium, home of the Negro Leagues, is poised for a comeback

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

As a member of the Old Tiger Stadium Conservancy, Gary Gillette fought the good fight. With the help of U.S. Senator Carl Levin, Gillette and his colleagues tried in vain to spare that historic Corktown ballpark from the wrecking ball.

Detroit development officials, of course, had other plans for "the Corner" and razed the original Navin Field configuration of Tiger Stadium back in 2009.

More than five years later, the city of Detroit is still entertaining proposals to redevelop the corner of Michigan and Trumbull. Meanwhile, the city of Hamtramck is entertaining ideas from another group Gillette is involved in called the nonprofit Friends of Historic Hamtramck Stadium.

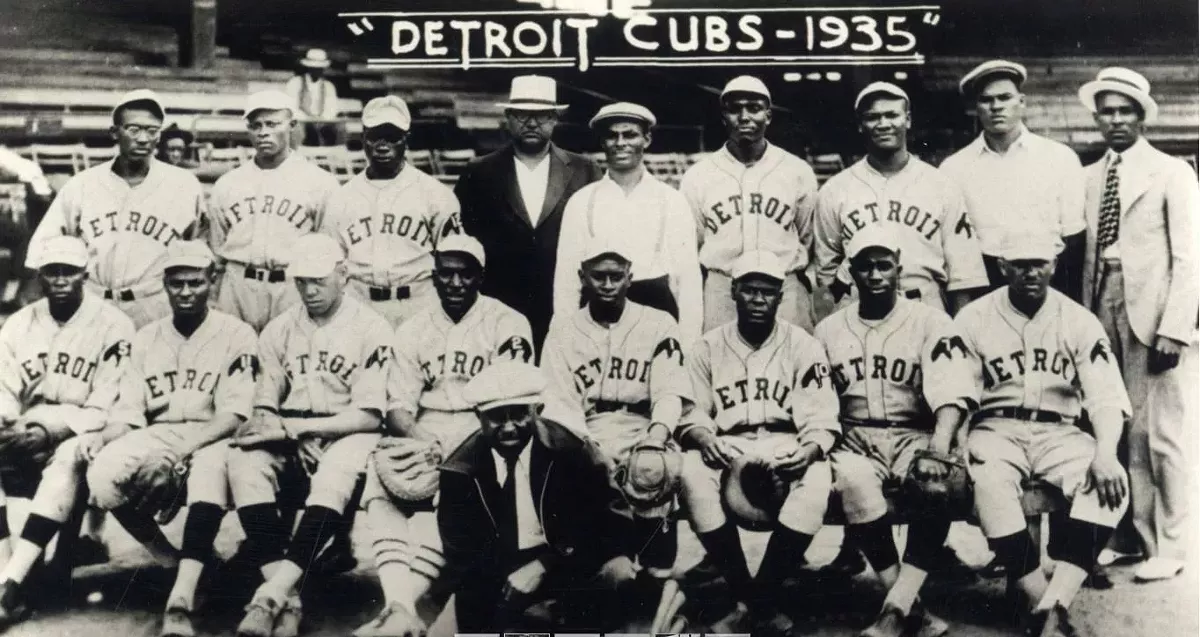

Hamtramck Stadium, which opened in 1930, was home to several Negro Leagues teams over the years, including Turkey Stearnes' Detroit Stars, and Cool Papa Bell's Detroit Wolves. It was also home to perhaps the greatest Little Leaguer who ever lived, Art "Pinky" Deras, who led his hometown team to victory in the 1959 Little League World Series.

The Stars left Hamtramck Stadium after the 1937 season, and the ballpark itself officially closed in the mid-1990s. It's been sitting fallow ever since.

Last summer, the state of Michigan recognized the preservation efforts of Gillette's group and, with members of Turkey Stearnes' family on hand, unveiled a new historical marker commemorating the ballpark's storied past.

Gillette, founder and president of the Friends of Historic Hamtramck Stadium, is also editor of the Emerald Guide to Baseball. He's also a former editor of the ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia and heads up the Detroit chapter of SABR, the Society for American Baseball Research. The man knows his baseball.

We caught up with Gillette recently to see how the restoration effort is coming along.

Metro Times: What are you hoping to accomplish with Hamtramck Stadium?

Gary Gillette: We're trying to preserve one of the few remaining Negro Leagues home ballparks, and the beauty of Hamtramck Stadium — aside from its history — is that it won't take a lot of money to preserve it because it's a small grandstand ... and it's in pretty good shape, considering how old it is. The goal is to renovate for community usage: baseball, soccer, and a dirt cricket pitch, as well.

MT: What compelled you to do this?

Gillette: It's like preserving any history. It has value because if it's gone, no one can experience it anymore.

MT: How many Negro Leagues ballparks are left in America today?

Gillette: I would say five or six, depending on how you count them.

MT: What was Hamtramck Stadium like when it first opened? Were there any local luminaries on hand?

Gillette: The big celebrity at the grand opening, aside from the mayor of Hamtramck, was Ty Cobb. It's unusual, you might say, that a noted baseball Southerner and racist would be throwing out the first pitch at a Negro Leagues ballpark, but he was good friends with the Stars' owner.

MT: Certainly an interesting choice. So who all played at Hamtramck Stadium over the years?

Gillette: It was the Detroit Stars' home field from 1930-31, '33 and '37. In 1932 it was the home of the Detroit Wolves. The Wolves were members of the (major) Negro East-West League. Many top-notch semi-pro teams, both white and black, played at Hamtramck Stadium in the 1930s.

MT: When people use the term "Negro Leagues," it can be a little vague. How many different leagues were there?

Gillette: There were seven recognized major Negro Leagues between 1920 and 1950, of which the Negro National League was the original and most famous. The Negro American League and the second Negro National League were the other most prominent.

MT: Which league did the Stars play in?

Gillette: The Detroit Stars were charter members of the original Negro National League. The 1920-1931 Stars played in the original Negro National League; the 1933 Stars played in the second Negro National League; the 1937 Stars played in the Negro American League.

MT: Who were some of the stars on the Stars?

Gillette: The biggest name was Turkey Stearnes ... they had another Hall of Famer, Pete Hill. There were several other Hall of Famers associated with the Stars, including Cuban pitcher José Méndez and left-handed pitcher Andy Cooper.

MT: The Stars' first home, Mack Park, on Detroit's east side, partially burned down in 1929. How did the Stars end up in Hamtramck?

Gillette: In 1930, that land in Hamtramck belonged to the Detroit Lumber Company. Most of the land was leased from the lumber company. The owner of the Detroit Stars, John Roesink, leased land from Detroit Lumber and maybe Calvert Coal to build a ballpark in the spring of 1930. In those days you could build ballparks really fast, partly because they were mostly wooden, and partly because you didn't have all of the rules to protect the workers (who were mostly white). You could work them like dogs, and you didn't have to pay them overtime. There was no OSHA or anything.

MT: Did Roesink employ many African-Americans?

Gillette: He didn't hire many African-Americans to work for the club or at the ballpark, and the ones he did he only gave menial jobs to. They would've had game-day jobs at the ballpark, selling concessions, maintenance jobs ... Roesink wasn't advertising in the black community, and in August of 1930, they conducted an economic boycott of the Stars because they claimed he was racist, which he was.

MT: Was the boycott effective?

Gillette: It was. Pretty quickly, John Roesink hired a black man to manage the club, to run the front office, and promised to spread some of his money around the African-American community.

MT: Who did he hire?

Gillette: He hired a man named Mose L. Walker [Not to be confused with Moses “Fleetwood” Walker] to be the Stars’ business manager. The club went bust a year later.

MT: But baseball continued at Hamtramck Stadium after the Stars?

Gillette: Yes, but there were no Negro Leagues games there after 1938. In 1940, Roesink lost the stadium to back taxes. The city of Hamtramck got control of the land, and it became city property. In 1941, the Wayne County Road Commission renovated the ballpark with WPA [Works Progress Administration] money. Then for three decades, Wayne County maintained it. Hamtramck Stadium officially closed in the mid-1990s.

MT: Josh Gibson played at Hamtramck Stadium. So did the immortal Satchel Paige. What made Turkey Stearnes so special?

Gillette: Turkey Stearnes is the greatest African-American baseball player in Detroit history, even though he never played for the Tigers. He was as good as Lou Whitaker, who should also be in the Hall of Fame. And as terrific a ballplayer as Willie Horton was, Turkey Stearnes is the best African-American player to play most of his career in Detroit. He's one of the top three or four home-run hitters in Negro Leagues history.

MT: Hamtramck Stadium's grandstand is a fascinating structure. What do you think when you look at it?

Gillette: I think that it's a diamond in the rough. ... It's an 85-year old ballpark where Negro Leaguers and Hall of Famers once played. There aren't many ballparks of any kind that have been around since 1930. It's rare and special because it's ours.

MT: What kind of support have you gotten so far?

Gillette: Comerica Bank was very generous in donating the money for the historic marker. The mayor of Hamtramck, Karen Majewski, City Council, and the Piast Institute have all been extremely helpful.

MT: What makes Hamtramck Stadium so significant?

Gillette: It's a relic of segregated Detroit, when African-American teams could not play at Briggs Stadium [which was later renamed Tiger Stadium]. When black men, no matter how talented, couldn't play in Major League Baseball. And when the African-American community was quite large and important in Detroit, but pretty much segregated from the rest of the city. And so now you have this little old ballpark where great men, 17 Hall of Famers, once played. It's a beautiful setting in a great place — and with some tender loving care, we can make this park an important part of the community again.

For more information on Hamtramck Stadium, find them on Facebook or visit hamtramckstadium.org.