Art movements are mostly mental constructs: When a painter stands before a new piece, the specific demands of the painting take precedence over everything else. No “ism” or group identity can replace the burning desire to work through that feeling, to get the latest inspiration that so wants to be realized onto the picture plane. Labels like “abstract expressionist,” “minimalist” or “Cass Corridor” come later, in the language of collectors and curators, the media and the marketplace.

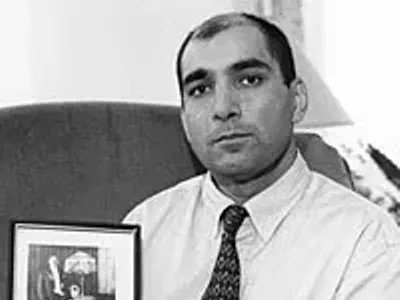

A shattering instance of personal vision, “Blue: The Life and Work of Bradley Jones” literally fills the walls of the Center Galleries. The show brings together a heaping eyeful of the artist’s output, along with photographs, sketchbooks and printed matter testifying to Jones’ pivotal position within what’s been called the Cass Corridor movement. In just over two decades — from the end of his student days in 1967 to the end of his life in 1989 — Jones produced an unbelievable series of gripping works, making it seem that he hardly stopped painting, writing poems or collaborating with others. But of course he also had time for obsessions and inner devastation, enough to make him bring it all to a close at the age of 45.

Though such losses are always tragic, rarely is the route of a person’s pain so vividly traced as in this overview. Jones’ early fascination with the paintings of Francis Bacon comes out in his approach to drawing, in the way he laid out images and in their harrowing content. Highly sexualized icons of women alternate with grim reminders of the mean streets of Detroit until, in the mid-’70s, a breakthrough occurs. The colors explode — the situations freak out with cartoon violence and libido, as if Peter Saul had downed a big frothy glass of Motor City madness.

Then in 1977-78, a series of “beach paintings” pumps the solitude up a notch. In one of Jones’ most successful works of this period, a woman-specter lounges with a blood-red drink before an impossibly bright, tropical landscape in retina-searing color. With the dislocation all in the details (her large red nipples and mouth, the knife-sharp contrasts and psychotic blue sky, the shadow of a pineapple that becomes a crawling thing), this idyllic subject and our expectations of it are completely subverted into something like the sunny anguish of Albert Camus’ The Stranger.

A decade later, Jones began to document the hopelessness of bar scenes in his “Purgatory Series.” Number 13 of that sequence portrays a couple locked in desire as a lone drinker across the table from them looks on. There’s an almost palpable longing here that turns into a comment on more than the personal, as if Jones’ isolated involvement gave him a front-row seat on our collective despair.

It’s more than ironic to realize, as we look into the show’s display cases containing mementos from Jones’ creative life, that this highly social man whose friends included some of the best minds of his generation (poet Ken and painter Ann Mikolowski of the Alternative Press, poet Jim Gustafson and painter Brenda Goodman, among many others) would make one of the most hopeless, solitary gestures imaginable. This testament is in the painting as well as in the poems that he continually produced:

Blank Canvas

I am standing at my studio window with

one hand pressed to the glass

my eye is looking beyond the hand

to a grey vista of factories and apartment houses

the street lights go on and it begins to snow

I watch for a long time as the street

fills up whitely, lovely with snow, snow

white as the canvas is white. white

as the hand is white. white

as if I could roll my eyes back in their sockets

until they too would be completely, lovely,

white.

That blankness, that void, is a presence running to overtake Jones in his last decade. Some of the penultimate paintings (always untitled, because their meaning is so bald-faced) are broken down into rows of smaller images depicting women disrobing and couples embracing. The artist renders those hugs as fleeting moments against the darkness within. Then a series of gritty street scenes projects an infinite loneliness into every molecule of 20th century urban life — as the fallen leaves of poverty, disconnection and suffering pile up.

The very last works are of two radically different kinds: First come three canvases each depicting a lovely mermaid — a sad, mythical message cast into the surrounding emptiness to anyone who’ll notice. And then just before giving up, Jones paints a group of self-portraits: the artist as faceless cipher in a corridor of such absolute nothingness as to be nearly impossible to digest. Gone are the beckoning sirens, the distracting imaginary ladies, and their songs. In their place is the endgame, the wordless word.

“Blue” makes all movements seem irrelevant, although like a searchlight in the Motor City sky, Jones’ passion and commitment illuminated the lives of his Cass Corridor associates and of those who come after.

George Tysh is Metro Times arts editor. E-mail him at gtysh@metrotimes.com