Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Zeena Marouf

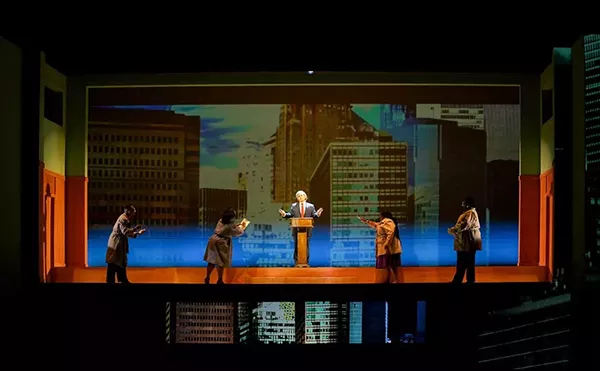

Kaylan Waterman at her sharing table in New Center.

By Monday morning, Kaylan Waterman's sharing table was nearly cleared out. By Monday afternoon, the table more closely resembled a corner at a well-curated local market, stocked with stacks of canned goods, rows of rice, noodles, instant meals, and condiments, a cooler filled with cold beverages, a variety of hygiene products, and bins of fresh produce. All of these items are free and available each day to those who need them.

Waterman is a musician and works as an operations manager at Assemble Sound in Detroit, where she also heads the nonprofit's residency program. She's fortunate to have been able to work from home during the coronavirus pandemic, which has allowed her some flexibility when tending to the table or assisting those with questions or requests. Sometimes she simply goes to her open window and talks to guests from there. A lot of her time, though, is spent identifying which items are in high demand and putting calls for donations on her social media pages.

The table, an idea given to her by her friend in Seattle who had launched a similar concept in their neighborhood, is situated under a tent in New Center, on Seward Avenue between Second and Third Streets, just outside of Waterman's apartment building. Watermen started the table on May 30 after she emerged from what she describes as being one of her lowest moments she can remember having in a long time. It was after George Floyd had died.

“I wanted to get the table started earlier, but so much kept happening. And I just wasn't able to get it off the ground. I got really busy. Then Ahmad passed. Breonna passed. And then George passed and I was very depressed. I was just very low,” she says.

Some days Waterman found it difficult to get out of bed. Others, she mourned alone or with family after she was struck with the belief that not even allies could be trusted.

“I'm a very action-based person, but his [Floyd's] death confirmed for so many of us that what we've been doing hasn't been working,” she says. “It's exhausting.”

By the time the Friday after Memorial Day rolled around, Waterman realized she needed to mourn constructively, not just for herself but for the community. She's been using the term “grief timeline” to explore why it is Black people are rarely granted permission to grieve or are forced into other people's grief timelines, neglecting their own emotional needs. For Waterman, she wanted there to be a way for her to grieve and disrupt the system at the same time.

“Marches are a disruption,” Waterman says. “And so is the sharing table. And people are so confused by the table because even we have been conditioned as far as how the economy is supposed to work and how give-and-take is supposed to look,” she says. “When I'm met with confusion, I literally tell them the table is here because you deserve it because we've been through enough and they're shocked because Black people never receive inherent trust, never received just inherent good faith. There's always gotta be some kind of earning or proving.”

Though Waterman purchased the first load of goods and supplies, as well as filling in here and there, the table has been mostly self-sustaining and propels itself. In fact, she often shares with people that since launching the project, Waterman is making most of her meals from those goods donated to the table. She's also found that many people, even if they are in need of an item, they will leave an item, too.

She prides the project on being a personalized free shopping experience, a stark contrast to someone coming to an impoverished neighborhood from another community in which they are reminded of their needs and what they lack. Waterman also does not want anyone to feel isolated or guilty for needing anything, no matter their circumstances. She says that while for many of us, quarantine has ended, there are many people who are too far behind after the economic fallout from coronavirus to catch up to post-quarantine life. Waterman has one frequent visitor to the sharing table whom she has told to come every day and to take whatever she needs — a Detroit mother who has yet to receive her stimulus check or unemployment benefits to support nine children.

“She's so behind, it doesn't matter a quarantine ended for her. And she doesn't even know how she's going to catch up,” Waterman says. “So, there's a lot of that, too. But I wanted to instill a sense of ownership on the block that they could also feel that they had kind of responsibility to. And so it's kind of a shared process for all of us.”

Though she started the table without permission from her apartment building, she's not really concerned with the consequences — in fact, she says she doesn't care. She hopes this inspires giving tables in other neighborhoods since people are now getting word about her table and some are walking blocks or getting rides to get essential items.

As marches and acts of protest continue across all 50 states and throughout the world, with no signs of slowing in intensity, Waterman doesn't know what will happen with the sharing table in terms of sustainability or growth. But ultimately she believes there is “no ceiling to what could happen.”

“We think that it has the potential to continue beyond this, because what we're in a moment of disruption,” she says. “And so the economy, our social environment, all of those things should look different after this, if there is an after this, you know? I really think that the sharing table, or at least something like it should be a part of that disruptive future in a lot of ways.”

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.