The party, in case you haven't been inside a bookstore in the past five years, is once again in full swing. "Silly Novels by Lady Novelists," as George Eliot so appropriately characterized them in her 1856 Westminster Review essay by that title, are not only back in vogue, popping up on the bookstore shelves and bestseller lists like candy-colored mushrooms in the front lawn of literature, but they are back in the critical eye as well. Now as then, pejoratives fill the air like autumn leaves.

The books are vapid, what Eliot called "a composite order of feminine fatuity," the plots flimsy and formulaic. And if in Eliot's day the characters sang a three-note opera of social-climbing ambition, upper-class accoutrement, and hopeful husband-hunting, today the husband-hunting and conspicuous consumption are intact, the social climbing replaced by a cocktail of magazine-cover yearnings and hapless urban frustration. The things Eliot called "silly" back then have today been deemed "froth" by women like Booker Prize nominee Dame Beryl Bainbridge. Average readers as well, perhaps influenced by the jelly-bean-colored covers, tend to assume that the average Chick Lit book is the prose equivalent of a Happy Meal.

They're not incorrect. The books are cutesy, trite, and in most cases poorly written. But that's not what's really the matter with Chick Lit. The problem is that when critics (professional or otherwise) rip into Chick Lit, what they're really scoffing at most of the time isn't the worn clichés, the puerile plots, or the graceless prosody, it's women. As a writer and editor with five books on the shelves whose work has been featured in magazines from Southwest Art to Penthouse — and specifically as a woman whose work deals in-depth with issues of sexuality and gender — I should know. Sexism has a long and storied history, and part of the game is that certain topics — the domestic, the mundane, the sensual, the emotionally fraught--have for centuries been feminized, associated with women in order to be dismissed. The literary equivalent of "you throw like a girl" is "you write like a girl."

I say all this not to excuse Chick Lit's failings — I personally can't stand 95 percent of what I've read of it — but to point out that most of the people who pooh-pooh it, including most of the feminists I've heard dissing the pastel-colored, shoe-festooned covers and the unthinking heterosexism that pervades every page, are being distracted from getting at what's really wrong with the genre. It isn't the writing, the packaging, or even the genre — it's the way these books deal, and fail to deal, with gender.

Let's not delude ourselves: We're talking about entertainment reading here. Entertainment comes in varying degrees of quality, of course, but our entertainment reading choices, by and large, are not precisely gems of deathless prose, world-changing philosophical tours de force, or breathtakingly unpredictable in their characterizations or narratives. The Chick Lit juggernaut of consumerist husband-hunting femme stereotypes is no less a pastiche (and in many ways no less a parody) of our culture's directives to women than, say, Tom Clancy or Dean Koontz novels are an identical war machine of the cultural directives aimed at men.

The difference? The ideal vs. the real; the golden godlike image of the archetypal man vs. the rumpled, insistently mortal imperfections of the day-to-day woman; the domestic and personal vs. the male "sphere" that is the rest of the world. The spy novel (since I mentioned Clancy), to take one genre directed at men, eschews mundanity in favor of holding up an impossible, unattainable, and often impossibly silly — why do you think Austin Powers worked so well? — fetish of a man in a man's world, idealized through men's eyes.

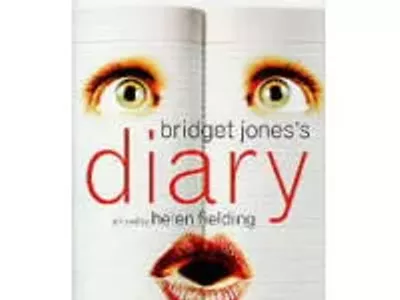

Chick Lit, on the other hand, tosses the role-modeling of ideal women straight out the window. Instead, the subject becomes the mundane workaday world, the world in which we care about our stupid bosses, self-absorbed boyfriends, still fitting into that pair of jeans, and whether we have a prayer in hell of having the kinds of magazine-cover lives we keep being told we can have if only we can manage to get it all right. That many of the novels are written in the form of diaries (Emma McLaughlin's The Nanny Diaries, Laura Wolf's Diary of a Mad Bride) or are styled as autobiographies (Laurie Notaro's Autobiography of a Fat Bride, Sherrie Krantz's The Autobiography of Vivian) should only make it clearer that these books are defiantly about minutiae, ordinary, and frequently vulgar. In these books idealism lives primarily in the "I shouldn't haves" of Shopaholic Rebecca Bloomwood's obsessive purchasing and in Bridget Jones' repeated catalogues of drinks drunk, cigarettes smoked, and unwanted pounds.

This is the very stuff author Doris Lessing referred to, in a 2001 BBC interview, when she said, "It would be better, perhaps, if [these authors] wrote books about their lives as they really saw them and not these helpless girls, drunken, worrying about their weight and so on," without apparently realizing that, in fact, this is precisely what many women do see. They (or should I say we, as a thirtysomething woman myself) have been carefully schooled since childhood to perform a meticulous and continual self-inventory in which they compare themselves from teeth to tits to toenail polish, salary to sling-backs to cellulite, to a constantly massaged, omnipresent, and unattainable ideal that appears in its myriad versions everywhere from women's history month filmstrips in grade school to the pages of Working Woman. For the workin'-girl twenty- and thirtysomethings that are the primary audience for Chick Lit, the resonance is deafening. Readers may well recognize that the degree to which it's all taken is often quasi-parodic (and many do seem to), but what drives the spiraling Chick Lit industry is empathy: I've had days like that.

It would not be unfair or inaccurate to say that the subject matter of Chick Lit is just one legacy of 20th-century feminism, its failures and triumphs equally intact. Caught between the rock of having our insecurities commodified and sold back to us and the hard place of having just enough autonomy, education, and economic clout to participate in the cycle, it's little wonder that today's Chick Lit is a literature of feminine dissatisfaction. It's also little wonder that the dissatisfactions are cloaked in self-deprecation, in humorously failed attempts to placate the insatiable ideals of perfectible hetero femininity, and, finally, in the characteristically breezy vernacular of the prose and the insufferably twee packaging. We laugh, achieving release through empathy, heartened that all the things we've been taught are so vital to our success as women are as difficult to attain for Andrea Sachs (lumpenprole protagonist of The Devil Wears Prada) and Rebecca Bloomwood (of the Shopaholic books) as they are for us. Our own dissatisfactions seem normal. Any outrage we might feel is mollified by the constant reminder that this is just the way it is, that there's nothing you can do about it, that it's best to just laugh it off.

This is, I think, what genuinely should be criticized about these silly novels by lady novelists: not their humor, not their tone, not their tissue-paper plots or their tiresome fixation on looks, but their obliviousness to their own words and what their words indicate. They are, to put it bluntly, not self-aware enough to realize that the constant low-grade misery they depict has larger causes and both larger and smaller cures. Insofar as these novels and their anti-role-model protagonists are nonetheless role models for their readers to some degree, that's a crying shame.

Faced with bilious criticism about the evils of pornography, sex activist Annie Sprinkle replied that "the solution to bad porn isn't no porn, it's better porn," thus spawning a generation of progressive, politically aware producers of smut and a pornography that is far better, more diverse, and more life-affirming than much of what preceded and surrounds it. Similarly, the solution to bad Chick Lit isn't to get rid of Chick Lit, it's making the effort to produce a Chick Lit that's more nutritious, more interesting, and just plain better.

This doesn't have to mean that realistic depictions of women's lives aren't worthwhile. What it means is depicting women's normal, everyday adaptability and strength. As with Jennifer Weiner's Good in Bed, published in 2001 (which, incidentally, I found nearly unreadable from a writerly standpoint), Chick Lit novels can easily and profitably introduce a bit of no-brainer revolution. In the case of Good in Bed, the laborious saga of self-loathing chunkster Cannie Shapiro and her road to the realization that her own very full life is in fact not such a bad one, the eventual admission is that worth and weight are not inextricably entwined, that one can be worthwhile and not be thin. Would it be so difficult for a Chick Lit novel to hold that premise throughout? Or, say, the idea that there is something to be said for maintaining a reasonably happy and engaging life, and sharing that with a man, rather than looking to a man and a romantic relationship to fix or complete one's life? I don't think so.

The alternative to obliviousness doesn't have to be ball-crushing anarcho-feminism. It can simply be woman-respecting, mildly progressive pragmatism. I, for one, would welcome a Chick Lit that backed up its cute shoes with a bit of clout. I want to see Chick Lit women who are able to overcome (even briefly) their tendency to flail, women whose strength may be imperfect but is nonetheless evident. What's really wrong with Chick Lit now isn't that it trades in floundering frustration, Jimmy Choo sandals, and helplessness over role-modeling, feminism, or, for that matter, proper grammar. What's wrong is that, in this incarnation as in the one George Eliot lambasted well over a century ago, it's too unconscious of itself to care.

Hanne Blank writes for City Paper, where the original version of this feature appeared. Send comments to [email protected]